For the European furniture sector, as in other industries, the COVID pandemic is casting a long shadow, with no certainty yet that the most dramatic swings in supply and demand are in the past. Several European countries, including France and Italy, were reporting record numbers of new daily COVID cases in the last week of January, the increase due to the emergence and rapid spread of the new Omicron variant, first detected in South Africa.

As a result, several European countries are once again in the grip of tight government lockdowns. This is clear from Oxford University’s “Stringency Index”, a composite measure of the level of lockdown across nine metrics (such as school and workplace closures, restrictions on public gatherings, stay-at-home requirements, restrictions on travel etc). On a scale of 0 (no measures) to 100 (strictest response), at the end of January the score for Germany (84) was the highest in the world, while Italy (77) and France (69) were also very high by international standards.

More positively, the Stringency Index for the UK, where the full effects of the Omicron variant first became apparent in Europe, was down at 48 as the government has moved to reduce restrictions as the current wave of the virus seems to have peaked. This has contributed to rising optimism that the Omicron variant, while highly infectious and still dangerous, does not lead to the same proportion of hospitalisations and deaths as previous variants, at least where a large proportion of the population is vaccinated or has been previously exposed to the virus.

So, while there is still no certainty, there is more confidence that the market situation for furniture in Europe will begin to “normalise” during 2022, at least to the extent that it will be less affected by sharp changes in demand and clogged up supply chains than in the previous two years. There is also greater clarity now on the immediate impact of the first few waves of the pandemic and a widening pool of data to work out what the longer-term effects of the pandemic might be.

Data on global furniture consumption just published by CSIL, the Italy-based furniture industry research organisation, shows that, after the initial shock when the pandemic hit in the first half of 2020, the European and wider global market for wood furniture picked up rapidly. According to CSIL “the prolonged period at home has influenced consumers’ priorities and how to buy products, with a strong growth in online purchases”.

CSIL also note that “the lockdown experience highlighted the importance of the home which acquired a new centrality both for living and working, becoming a new fulcrum of our daily activities”.

This in turn fed into changes in the types of furniture required by European consumers. According to CSIL, “spending more time at home pointed out the usefulness of having functional spaces for the whole family, possibly modular furniture also suitable for working from home. Thus, great attention has been put to the home office environment, but also to the kitchen, the comfort segments (from mattresses to upholstery) and the outdoor furniture”.

This led to a greater proportion of spending being directed towards furniture as “consumers invested in improving their living spaces, often allocating to furniture substantial portions of income made available because of decreased expenditure for restaurants, vacations and other leisure activities”.

The overall effect was to limit the scale of the contraction in furniture consumption during the initial phase of the pandemic. CSIL estimates that the value of furniture purchased worldwide in 2020 was US$415 billion, around 6% less than the previous year (when considered in apparent consumption valued at production prices excluding retail mark-up).

The contraction in 2020 was particularly large in the office furniture sector, following the decline in investment by both industry and the service sector, but demand in other sectors including kitchens and outdoor furniture remained more resilient.

Such was the strength of the rebound last year, driven by the boom in consumer spending on furniture, CSIL reckon that worldwide furniture consumption was already back to the pre-pandemic level in 2021. The recovery is expected to strengthen and widen, in terms of geographic scope, during 2022.

The CSIL forecast for furniture consumption growth in the EU, UK, and European Economic Area (EEA) countries – at 4.4% in 2022 – is particularly encouraging, being the largest for any global region. However, this partly reflects a weaker rebound compared to other regions – particularly the US – last year. CSIL reckon that the extra government stimulus from the EU Recovery and Resilience Facility – which is filtering through rather more slowly than national level stimulus measures around the world – will be a particularly important driver of consumption in the EU during 2022.

CSIL reckon that furniture consumption worldwide will grow by around 3.9% this year, with growth in North America expected to be 4.0%. Growth in other areas of the world is expected to be somewhat slower including Asia and the Pacific forecast (3.8%), the Middle East and Africa (3.3%), Europe outside the EU inclusive of Russia and Turkey (3.0%) and Central and South America (3.0%).

CSIL’s optimistic assessment of near-term strong furniture market growth at a global level is reflected in other analysis. For example, Statista’s Consumer Market Outlook estimates that revenue from the global furniture industry, which hit $1.3 trillion in 2020, will rise consistently to reach $1.6 trillion by 2025.

Furniture supply chain disruption leading to rising prices

While long-term prospects for the European and global furniture sector look very promising, the shorter-term impact of the pandemic continues to be felt in supply chain disruption.

In the last two years, furniture suppliers have had to respond to temporary, but unpredictable and often lengthy, shutdowns in manufacturing facilities, staff shortages, severe limits on travel by business managers and sales and maintenance staff, material shortages and sharp rises in material and energy prices, limited container space and a massive hike in freight rates, store closures and other restrictions on retailing activities.

The combination of continuing strong demand, rising costs and tight supply is now being felt in sharply rising consumer prices for furniture in Europe. For example, a report in the Guardian, a UK newspaper, on significant price hikes after Christmas, quotes an IKEA representative as follows:

“Since the start of the pandemic, IKEA has managed to absorb the significant cost increases experienced across the supply chain while keeping prices as low and stable as we possibly can. Now, like many other retailers, we have had to raise our prices to mitigate the impact on our business. Price increases vary but remain in line with what we are seeing globally at IKEA, which is approximately a 9% average increase across countries and the product range”.

The sharp rise in prices is also reflected in the latest figures from the UK Office of National Statistics (ONS). These show that UK furniture retail prices reached another all-time high in November last year, following previous records in the preceding 2 months. Prices in November 2021 were up by 12.2% compared to the same month in 2020. The annual rises recorded in October and September were 11.3% and 10.5% respectively.

The price rises in the UK were significantly higher for imported products than for domestic production. Factory gate price of all UK furniture destined for the home market was up by 4.7% compared to November 2020.

Strong consumer demand combined with constraints on supply of imported products have bolstered the position of domestic furniture producers in the UK. ONS data shows that during the first three-quarters of 2021, the total value of turnover and orders for UK furniture manufacturers was £6.6 billion, up 28% on the same period the previous year. Orders of £901.6 million in September 2021 were the highest for any single month since the series began in 1998.

However, domestic furniture producers in the UK, as elsewhere in Europe, are now suffering the effects of record price rises for materials and energy supplies. ONS figures show that the cost of materials and fuel for UK furniture manufacturers in November 2021 were 22.1% higher than the same month in November 2020.

Similarly, the British Furniture Manufacturers (BFM) State of trade survey for October 2021 showed that while furniture manufacturers were still confident in the trading environment, the price of raw materials was pressurising margins and cash flow. Labour costs were also on the rise. Skill shortages were reported by more than three quarters of respondents and in some cases the lack of suitable labour was severe.

The BFM survey reported an average cost increase of more than 20% for Board, Plywood, Timber, Steel and Springs. And, across all materials covered in the survey, the average increase stated was 15%, up from 8% recorded in April, with surcharges being applied to some materials. This led to a significant proportion of manufacturers to raise product prices. Therefore, the recent relative competitiveness of domestic furniture manufacturers in the UK may prove short lived.

European furniture companies diversify supply to spread risk

While recent logistical challenges may have given a temporary boost to the European furniture industry in their home market, the longer-term trend is towards increasing import penetration.

In their latest report on the global furniture sector, CSIL note that “the European market is highly integrated, with major chains and manufacturers working on a European scale. However, slight but continuing market openness is registered. The origin of products sold on the market has also changed and markets are continuously open to imported items. This is evident if we consider the last decade when national production share has been decreasing, while Asian and Pacific imports have been increasing”.

CSIL also highlight that one significant effect of the pandemic may be to encourage European retailers to diversify their suppliers as a means of spreading risk. According to CSIL “Diversifying industry suppliers may occur, not relying on single suppliers, but finding ways to make use of components that can be sourced from many different locations. Some large players in the global furniture industry implement strategies of diversification of manufacturing plant’s locations”.

CSIL also point to the fact that, while the furniture sector everywhere, including Europe, tends to be highly fragmented with limited consolidation, Europe is host to a relatively large share of the large players that do exist. In fact, 87 of the top 200 furniture manufacturers worldwide are based in Europe. Some of these companies have internationally integrated supply chains and have started to produce more product outside Europe. European companies are particularly significant at the luxury end of the market and joint ventures with European players have been particularly attractive to other global firms keen to enter this segment.

The larger firms in Europe are also tending to outperform the smaller companies, a trend which so far has been reinforced by the pandemic. CSIL data shows that between 2015 and 2020 period, the top 100 companies in Europe increased revenues by 15% during a period when total European furniture production was almost stagnant.

During the pandemic, the larger companies have had more resources to draw on to tide them over periods of lockdown and to respond to supply chain disruption and to build new sales channels. There has been a very substantial shift to selling furniture online in Europe, a trend that has been driven by giants such as Amazon and IKEA.

In 2019, IKEA saw revenue fall to €39.6 billion in 2020 due to the pandemic, after two decades of growth. However last year, IKEA’s sales bounced back to €41.9 billion, slightly exceeding 2019, with e-commerce sales up 73%.

New on-line business models in the furniture sector

It’s not only the existing names like Amazon and IKEA that have benefited from the shift to on-line furniture sales. There is also a new breed of companies focused almost exclusively on selling furniture online.

This breed is exemplified by MADE, a UK based company launched with £2.5 million of funding in 2010, but which last year completed its IPO on the London Stock Exchange with a market capitalisation of £775 million. MADE sales in 2020 reached £315 million, around 50% in the UK and 50% in continental Europe. Sales in the first half of 2021 were £214 million, up 54% year-on-year growth.

The MADE business model is very different from that of IKEA, avoiding overheads by not owning any factories and with only a very small number of showrooms. Instead, the company relies on online sales and building close working relationships with designers and factories and sourcing products globally.

But of course, companies experiencing such rapid growth in sales are not immune to the current supply chain challenges. In December MADE issued a profit warning stating that up to £45m-worth of orders have been delayed blaming factory shutdowns in Vietnam, clogged ports and extended shipping times. Sales this year are now expected to be around £365 million, down from £410 million estimated earlier, but still a gain of 16% compared to the previous year.

Another exemplar of a new business model in the furniture sector, again exploiting new technology and innovative sales channels but this time for the benefit of small-scale craft-based production in the tropics, is provided by Artisan Furniture. This company featured in a recent article in Forbes, the business journal, under the heading “innovation to maintain market access for artisans”.

Artisan Furniture is a U.K. business wholly reliant on village craftsmen in Jaipur, India, which Forbes notes has proved resilient throughout the pandemic, racking up double-digit growth and now on an expansion path with financial support from Goldman Sachs GS. The company markets and claims a price premium for authentically Indian-made and hand-crafted wood furniture products to retail partners such as TKMaxx, the European subsidiary of apparel and home goods group TJX Companies, and Spain’s leading department store group El Corte Inglès.

The Artisan Furniture business model has also involved creating a niche online marketplace for artisan-only products. The company’s “dropship furniture programme” is described as a “no storage model that lets retailers ship products directly to their client’s doorstep while also giving artisans the freedom to craft products using techniques they know best”.

The company is exploiting rising consumer awareness about the environment and corporate social responsibility with an emphasis on support for local craftspeople and their communities, and products made from sustainable, commercially planted woods like mango and sheesham. The Forbes article suggests that Artisan Furniture has helped ensure long-term prosperity for several villages around Jaipur where more than 350 artisans form part of the furniture company’s supply chain.

China makes biggest gains as EU27+UK wood furniture imports rise

Recent trends in European imports of wood furniture need to be seen against the background of rapidly increasing demand, irregular availability of supplies from many countries, sharply increasing prices across the board, and efforts by European retailers to mitigate risks by diversifying supply sources.

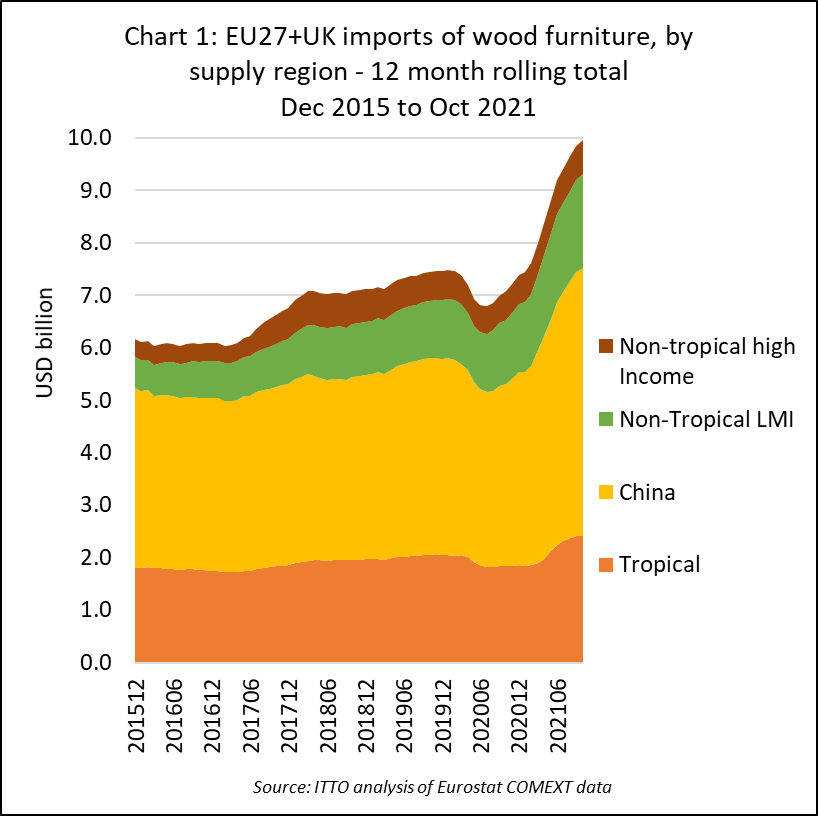

From the trade data, it is clear that a very large increase in the value of wood furniture into the EU27+UK followed on immediately from the more minor dip during the early stages of the pandemic in the first half of 2020. In fact, the 12-month rolling total level of imports was close to US$10 billion by the end of October last year, which compares to less than US$7.5 billion just before the pandemic in the opening months of 2020 (Chart 1).

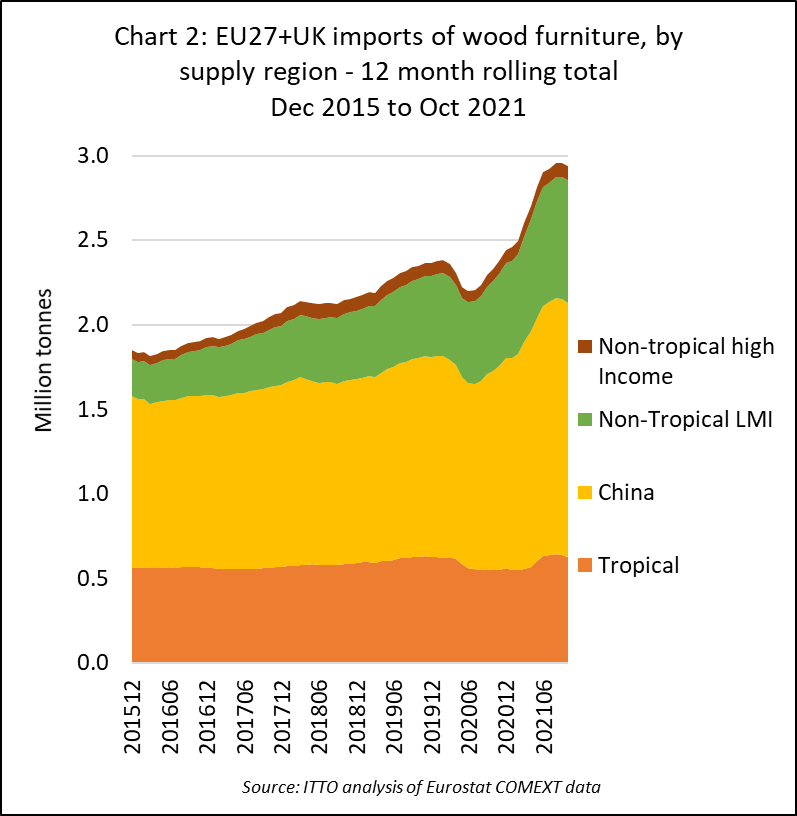

The rise in import value was partly driven by increasing product prices and freight rates. The average unit value of EU27+UK wood furniture imports increased from US$3030 per tonne in the first ten months of 2020 to US$3460 in the same period last year. However, import quantity did rise from 2.4 million tonnes in the 12 months to February 2020, just before the onset of the pandemic, to nearly 2.9 million tonnes in the 12 months to October 2020 (Chart 2).

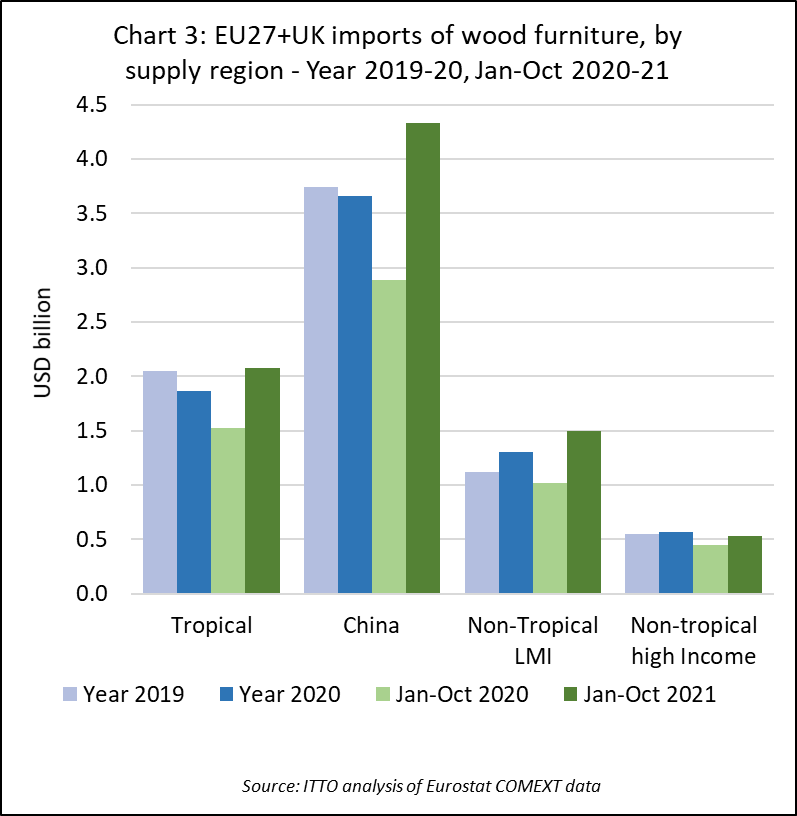

In the first 10 months of 2021, the EU27+UK imported US$2.08 billion of wood furniture products from tropical countries, 36% more than the same period the previous year. While a significant rise, it should be noted that, for tropical countries, around two thirds of the gain in European import value was due to price increases and rising freight rates. EU27+UK import quantity from tropical countries in the first 10 months last year was 523,000 tonnes, only 14% more than the same period the previous year. Import quantity from tropical countries for the whole of last year is projected to be around 600,000 tonnes, no more than the long-term annual average between 2015 and 2019.

The rise in import value of wood furniture from tropical countries last year also pales in comparison to the rise in import value from China. In the first 10 months of 2021, the value of EU27+UK imports of wood furniture from China totalled US$4.34 billion, 50% more than the same period the previous year (Chart 3). Import quantity from China was also up over 50%, at 1.25 million tonnes. Imports from China have benefitted from more reliable shipping and higher availability of containers compared to tropical countries in Southeast Asia. One legacy of the US-China trade dispute has also been to increase China’s focus on exports to the European market as exports to the US have declined.

The gains in EU27+UK imports of wood furniture from other Lower and Middle Income (LMI) countries in non-tropical regions also exceeded the gains made by tropical countries. Import value from non-tropical LMIs in the first 10 months of 2021 was US$1.50 billion, 47% more than the same period the previous year. Import quantity from these countries increased 37% to 606,000 tonnes.

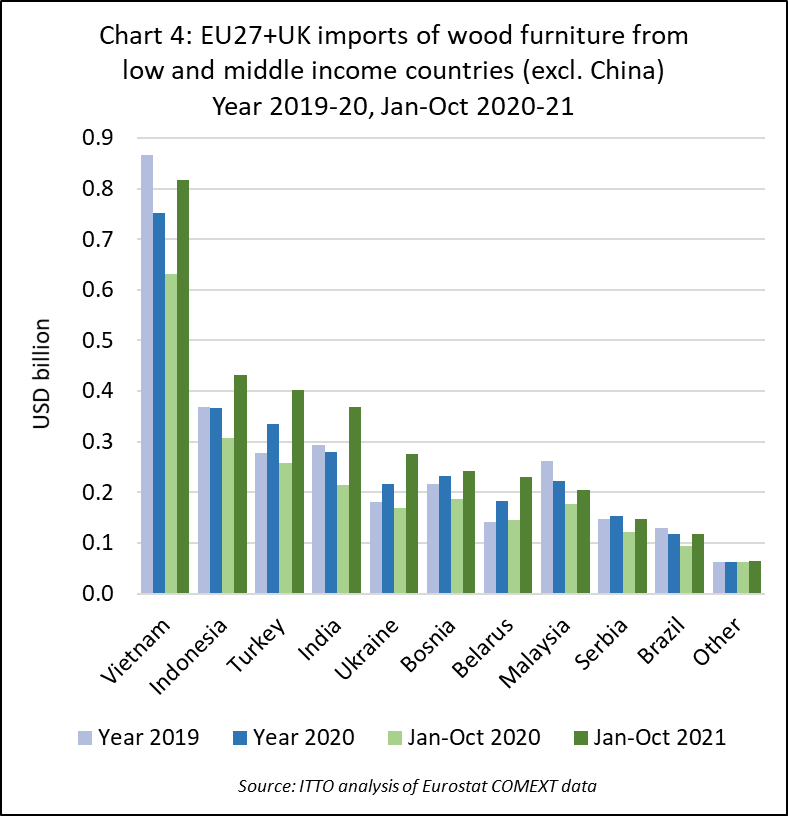

Chart 4 highlights that the major gains in EU27+UK import value of wood furniture from tropical countries in the first 10 months of 2021 were made by Vietnam (+30% to US$820 million), Indonesia (+40% to US$430 million) and India (+72% to US$370 million). Import growth from Malaysia was more moderate, rising 16% to US$200 million.

The signs are that Indonesia is seeing some benefit from the commitment to market development in the EU building on industry-wide SVLK certification and being the only country offering FLEGT licenses. Suppliers in India, most of which are selling craft products into the EU27+UK, are benefitting from the development of innovative on-line sales channels like that described earlier for Artisan Furniture. The slightly slower rate of increase of EU27+UK imports from Vietnam is probably only a reflection of supply bottlenecks, particularly as Vietnam is also now shipping vast quantities of wood furniture out to the US.

Of non-tropical LMI countries, EU27+UK imports of wood furniture increased particularly strongly in the first 10 months of 2021 from Turkey (+56% to US$400 million), Ukraine (+64% to US$280 million, Bosnia (+30% to US$240 million) and Belarus (+59% to US$230 million).

These countries in the European neighbourhood have been major beneficiaries of supply and logistical problems in more distant supply countries. One sign of this was the announcement by IKEA in October last year of a plan to shift more production to Turkey to shorten the supply chain, and minimize problems associated with rising shipping costs and lengthening delivery times from other parts of the world.

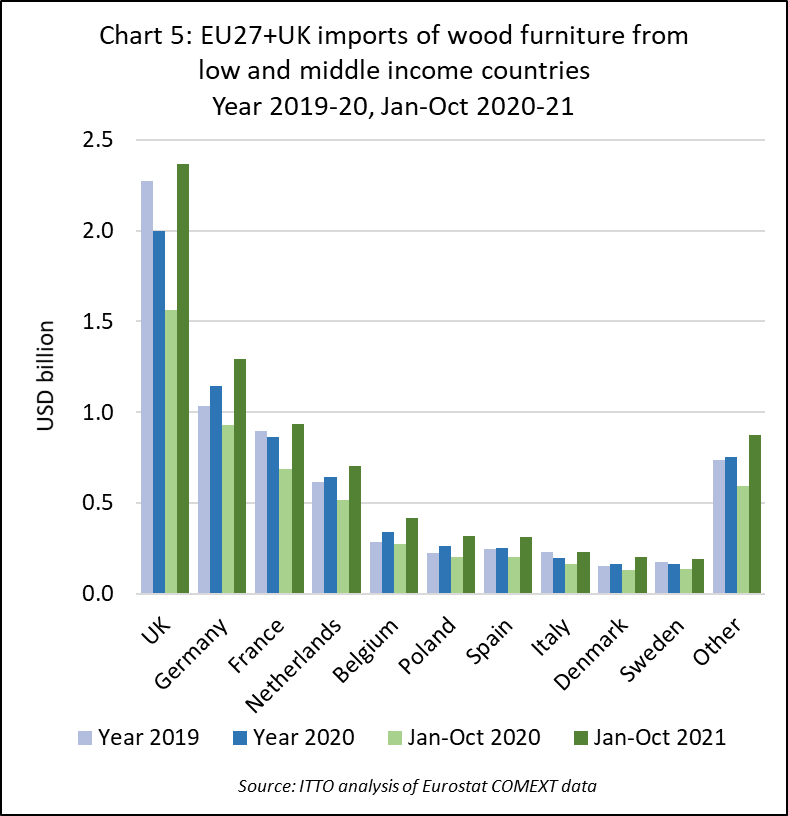

The UK is by far the largest European importer of wood furniture from Low and Middle Income countries, importing 83% more than the next largest, Germany, in the first ten months of last year. During that period, imports by the UK increased 51% to US$2.37 billion, although this followed a particularly large 12% fall the previous year.

In the first ten months of last year, there was also a large increase in wood furniture imports from LMI countries into all the leading markets including Germany (+40% to US$1.29 billion), France (+36% to US$940 million), Netherlands (+36% to US$700 million), Belgium (+52% to US$410 million), Poland (+57% to US$320 million), Spain (+54% to US$310 million), and Italy (+42% to US$230 million) (Chart 5).

Milan furniture show pushed back to summer

Instead of being held in April this year, the 60th edition of Salone del Mobile in Milan will be held from 7-12th June 2022, prompted by “the desire to organise an event that fully reflects the importance and the quality of the fair” according to the event organiser.

Show president Maria Porro comments: “The decision to postpone the event will enable exhibitors, visitors, journalists and the entire international furnishing and design community to make the very most of an event that promises to be packed with new things, in total safety.

“As well as celebrating a major anniversary, the event will focus on the theme of sustainability, acting as a showcase for the progress made in this regard by creatives, designers and companies. Moving the event to June will ensure a strong presence of foreign exhibitors and professionals, which has always been one of the Salone’s strong points, and it will also give the participating companies time to plan their presence at the fair as thoroughly as possible given that, as we know, the progression from concept to final installation takes months of preparation”.