UK GDP increased 7.5% in 2021, the fastest annual growth rate in the UK since the second world war and making the UK one of the world’s fastest growing economies last year. But this “rise” must be considered in the light of the UK being amongst countries worst affected by the COVID-19 pandemic which led to a 9.4% fall in GDP in 2020 at a time when there was already uncertainty due to the country’s departure from the EU.

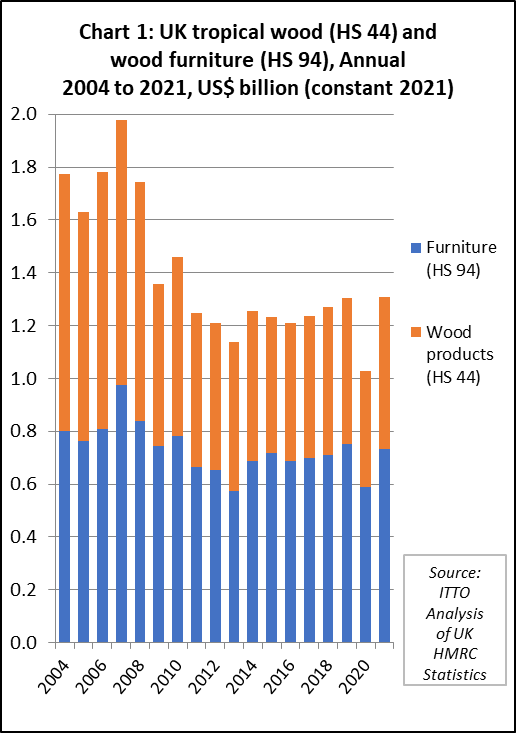

UK imports of tropical wood and wood furniture products have mirrored the rollercoaster ride in the wider economy. Total UK tropical wood and wood furniture imports in 2021 were USD1.31 billion, 27% more than the previous year. This followed a 21% decline in 2020 when supply and demand were severely affected in the early phase of the pandemic. In practice, the value of UK imports of tropical products last year was only a marginal gain compared to USD1.30 billion in 2019 before the pandemic and is no significant increase on the long-term average in the last ten years (Chart 1).

While UK imports of tropical wood and wood furniture increased last year, tropical products have suffered a significant loss of market share during the pandemic (Chart 1b). The total value of UK imports of wood and wood furniture products from all countries increased from USD8.94 billion in 2020 to USD12.65 billion last year, a gain of 42% after a 5% fall the previous year. The share of tropical products in total imports was only around 10% last year, well below the long term average of between 13% and 14% share.

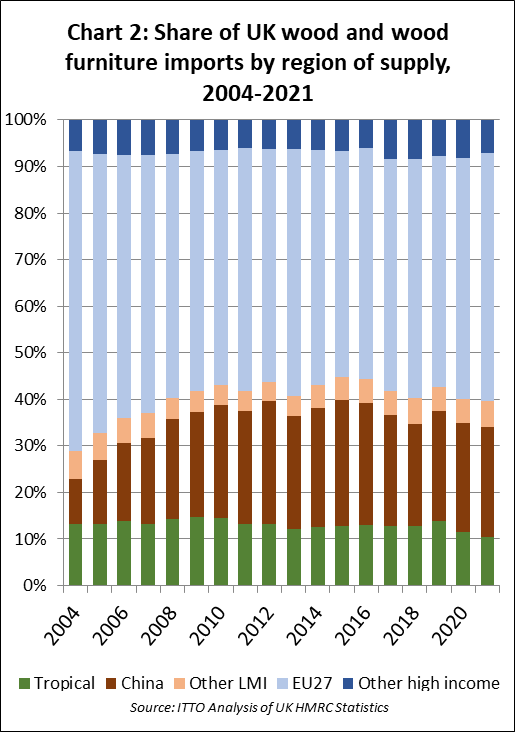

In contrast to tropical products, the share of UK import value of non-tropical products from China remained level at 23.5% in 2021, as value increased by 43% to USD2.99 billion during the year. The share of UK imports of non-tropical products from other lower and middle income (LMI) countries increased from 5% to 6%, as value increased by 57% to USD720 billion in 2021. This was largely due to a near doubling in UK imports from Russia and Turkey during the year.

However, in terms of absolute value, the largest gains in UK imports during 2021 were made by EU27 countries. The total value of UK imports of wood and wood furniture from the EU27 increased 46% to USD6.73 billion in 2021. This followed only a 1% decrease the previous year, despite the onset of the pandemic. The share of EU countries in UK imports increased progressively from 49.5% in 2019 to 52% in 2020 and 53% in 2021. Expectations that the UK’s departure from the EU might lead to a decrease in the share of imports of wood and wood furniture from the EU and a switch to other regions have yet to be realised.

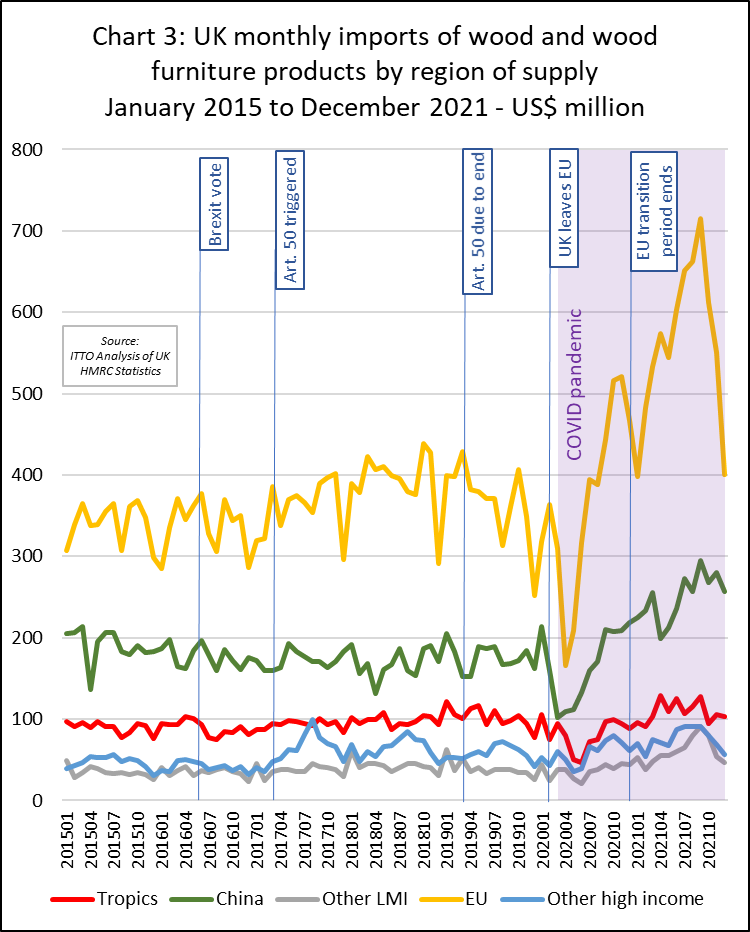

Recent trends in UK wood and wood furniture imports are, of course, strongly influenced by the combined effects of the pandemic and Brexit, effects tracked on a monthly basis in Chart 1c.

In the two and a half years following the UK’s decision to trigger Article 50 of the EU Treaty on 29 March 2017 which began the formal process for withdrawal from the EU, a process eventually completed January 2020, UK imports of wood and wood furniture from the rest of EU were more volatile than usual. However, there was no significant change in share of overall UK imports sourced from the EU and other regions of supply during this period.

The pattern changed dramatically from February 2020 just after the UK’s departure from the EU and with the onset of the pandemic. This led to a sharp, but very brief, downturn in UK imports of wood and wood furniture from all regions, including the EU, during the first period of lockdown in April and May 2020.

But UK demand for wood products increased rapidly thereafter as consumers spent less money on transport, holidays and eating out, and invested large sums in home and garden improvement. Spending was further boosted by low interest rates and a huge injection of government support to tide the economy over the pandemic.

The sharp recovery in demand in the UK in the second half of 2020 and in 2021 coincided with a severe shortage of container space and other logistical problems in other parts of the world leading to a big rise in UK wood products imports from the EU.

At the same time, the full effects of the new customs controls on imports from the EU following the UK’s departure from the EU were yet to be felt last year. Unlike the EU, which immediately imposed full inspections on imports from the UK in January 2021, when the Brexit transition period came to an end, the UK introduced a phased approach. A grace period was granted to UK importers to give them more time to adapt to the new rules and ways of working.

The UK’s originally intended that requirements for phytosanitary certification of UK imports from the EU would be introduced from April 2021 while requirements for full customs declarations on entering the UK market, rather than submitting forms at a later date, would be introduced from July 2021. However, these deadlines were progressively pushed back during 2021. In the end, full customs declarations and controls on UK imports from the EU were only introduced on 1 January 2022, while requirements for phytosanitary certification and physical sanitary checks on controlled products are now only due to be introduced on 1 July 2022.

It seems likely that the huge surge in UK imports of wood products from the EU in the first three quarters of 2021 was partly driven by the desire of UK importers to build stock in advance of introduction of full customs checks. The pace of UK imports from the EU fell dramatically in the last quarter of last year, with importers carrying higher stocks into the (typically slower) winter season and with some signs of slowing construction sector activity.

Uncertain UK prospects as economic and logistics problems mount

Now there is a considerable uncertainty as to how UK imports will develop during 2022, both in terms of absolute numbers and in the balance between imports from the EU and the rest of the world.

The headline figures look quite promising. The latest OECD outlook indicated that the UK economy will continue to recover in 2022 with overall growth moderating to 4.7% during the year. Construction activity in the UK has been robust and seems quite resilient, despite material shortages and rising energy costs. The IHS Markit/CIPS UK Construction Purchasing Managers index registered 56.3 in January, up from 54.3 in December, the strongest rate of output expansion since July 2021.

At the same time, concerns about the effects of the COVID omicron variant have waned in the UK as cases and deaths have fallen sharply in recent weeks and the UK government has indicated that all COVID restrictions should be lifted before the end of February.

On the downside, consumer price inflation in the UK is currently around 5.4%, with energy prices rising very rapidly . A recent article in the Financial Times (FT) notes that UK growth rate has also been artificially boosted by £25bn of corporate tax incentives and that real business investment remains weak. In the third quarter of 2021, investment was still 4% below pre-pandemic levels, lower than any other economy in the G7. And UK exports have not joined in the global boom. According to the FT, “all this suggests that businesses are looking relatively unfavourably on the UK, even before corporation tax rates rise from 19 per cent to 25 per cent in 2023”.

As to where the UK will turn to for wood products during 2022, that will heavily depend on supply side issues, including access to log supplies, availability and prices for containers, shifting exchange rates, level of demand in other markets, as well as policy measures.

It seems unlikely that UK imports from the EU in 2022 will be anywhere close to the level of 2021 as customs controls are finally introduced and merchants are carrying heavier stocks than the same time last year. On the other hand, problems of shipping and transport logistics have become particularly prominent in the UK market in recent months and these may yet tie importers even more closely to their traditional European suppliers of wood products, irrespective of Brexit.

A recent study conducted by global logistics platform Container xChange and applied research organisation Fraunhofer-CML revealed that the UK currently has the world’s longest turnaround times for processing shipping containers. Due to the combined effects of Brexit and COVID, it is taking an average of 51 days for cargo boxes carrying goods from China and Southeast Asia to be processed in UK ports due to port congestion, shortage of warehousing space and lack of truckers and other qualified staff. This compares to around 25 days in Germany (the next worst performing European country) and as little six days in China.

The problems of shipping into the UK have led to more calls for distributors and manufacturers to shift away from their existing “just-in-time” business model to a “just-in-case” model of bringing more manufacturing closer to home and increasing inventories once again. In practice, this implies a continuing high level of dependence on the large suppliers in continental Europe for which turnaround times, while much longer than before the UK left the EU single market, still compare favourably to imports from other parts of the world.

There are a few positive signs that global supply chains may start to unclog before the end of this year. For example, the FT was told by shipping giant AP Moller-Maersk that it expects global supply chain struggles to slowly get back toward normal in the latter part of 2022. And while global container prices have been very volatile around Chinese New Year, they have eased a little from the heights reached in the third quarter last year.

But overall, on-going supply side problems, which are particularly pronounced for shipments into the UK, suggest that there is unlikely to be a more significant upturn in UK imports of wood and wood furniture products from tropical countries during 2022.