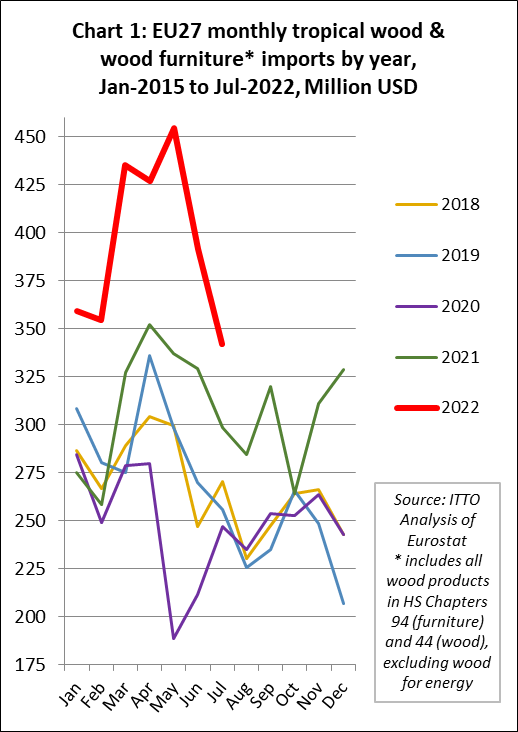

The most recent EU27 trade data to end July this year shows that imports of tropical wood and wood furniture products were still at historically high levels in the early summer months this year. However, imports were slowing from the peak reached in May. Now, as Europe moves into the winter months there are ominous signs of recession ahead, particularly as the war in Ukraine is contributing to huge increases in energy prices and business and consumer confidence is being hit by expectations of higher interest rates to control inflation.

In the first seven months of this year, the EU27 imported tropical wood and wood furniture with a total value of USD2.76B, a gain of 27% compared to the same period last year. Part of the gain in EU27 tropical wood product import value was due to a rise in CIF prices. In quantity terms, EU imports of tropical wood and wood furniture products in the first seven months of this year were, at 1,190,200 tonnes, up 14% compared to the same period in 2021. The level of imports in June and July, while still high compared to previous years, were also sharply declining in June and July from the hights reached between March and May (Chart 1).

The high level of imports in the first seven months this year was driven by the combination of a sharp fall in the value of the euro against the dollar, continuing high freight rates, and severe shortages of wood and other materials.

Since the start of this year, the value of the euro has declined around 15% against the US dollar and is currently at the lowest level for 20 years. In mid-July, the euro hit parity with the US currency for the first time since 2002 and fell to a low of 0.95 against the dollar at the end of September. The euro’s slide underlines the foreboding in the 19 European countries using the currency as they struggle with an energy crisis caused by Russia’s war in Ukraine.

The curtailment of wood supplies from Russia and Belarus due to the sanctions imposed by the EU following the invasion of Ukraine in February has opened up new opportunities in the EU market for some tropical wood products, notably plywood and decking for which Russian birch and larch products have been important substitutes.

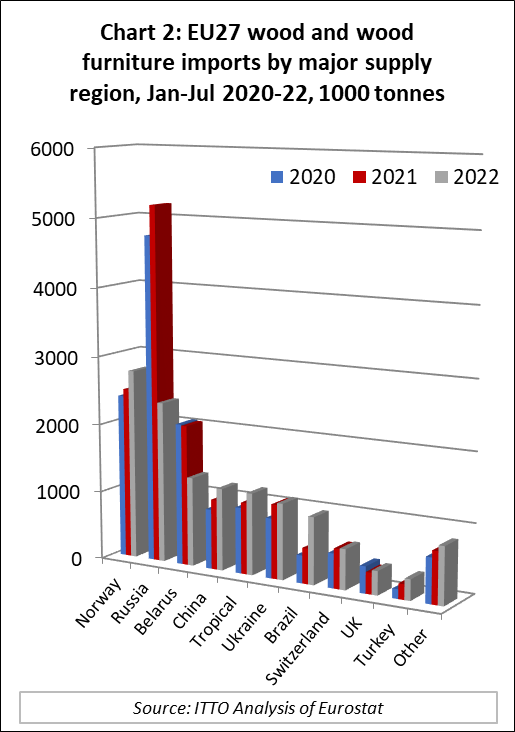

In the first seven months of this year, tropical products accounted for 9.2% of the quantity of all wood and wood furniture products imported into the EU27, which compares to 6.8% during the same period in both 2021 and 2020. The gain in tropical wood share is due mainly to a large reduction in imports from Russia (-55% to 2.34 million tonnes) and Belarus (-37% to 1.30 million tonnes) during this period. After an initial fall in the early months of the war, EU27 imports from Ukraine recovered some ground in the second quarter and by the end of the first seven months of this year were, at 1.11 million tonnes, only 3% down on the same period in 2021 (Chart 2).

While tropical wood has made gains in the EU market this year, the largest beneficiaries of the opening supply gap due to the fall in imports from Russia and Belarus have been non-tropical wood products from Norway (+11% to 2.77 million tonnes), China (+17% to 1.20 million tonnes), Brazil (+90% to 976,700 tonnes), Turkey (+38% to 304,200 tonnes), Chile (+67% to 66,900 tonnes), and New Zealand (+24% to 34,800 tonnes).

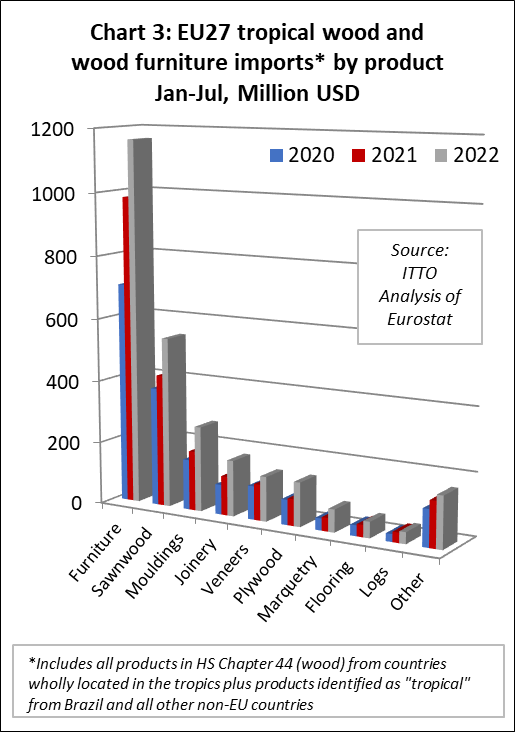

While not benefitting as much as other supply countries, there were increases in EU27 imports of most wood product groups from tropical countries in the first seven months of this year (Chart 3). For wood furniture, import value of USD1163M during the January to July period was 18% more than the same period last year, although import quantity was down 5% at 235,200 tonnes. For tropical sawnwood, import value of USD543M was 29% up on the same period last year while quantity increased 25% to 447,600 tonnes. Import value of tropical mouldings/decking was USD271M in the first seven months of this year, a gain of 43% compared to the same period in 2021, while quantity increased 3% to 117,000 tonnes. There were also large gains in EU27 imports of tropical joinery products (+43% to USD178M, +29% to 67,000 tonnes), tropical veneer (+24% to USD142M, +25% to 94,800 tonnes), plywood (+66% to USD141M, +30% to 82,200 tonnes), marquetry (+69% to USD73M, +49% to 12,400 tonnes), flooring (+33% to USD51M, +23% to 16,500 tonnes) and logs (+14% to USD37M, +12% to 61,600 tonnes) .

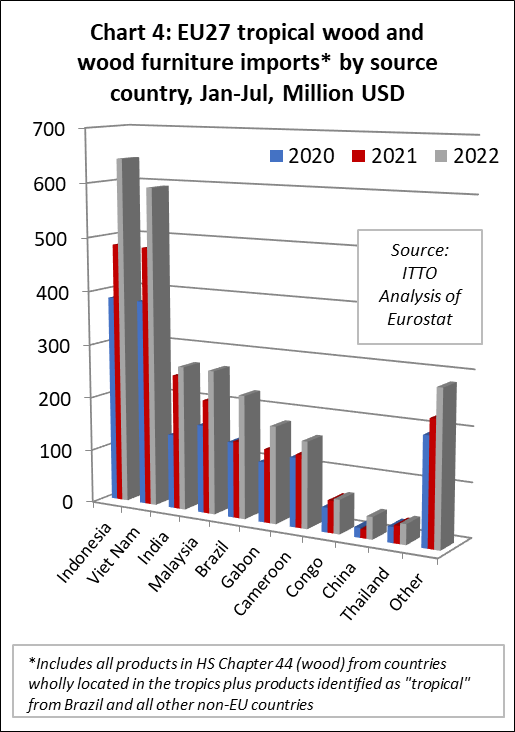

In terms of source countries, EU27 imports of wood and wood furniture in the first seven months this year was up significantly compared to the same period last year from Indonesia (+33% to USD643M, +6% to 162,600 tonnes), Vietnam (+23% to USD593M, +4% to 138,400 tonnes), Gabon (+32% to USD179M, +29% to 160,400 tonnes), Brazil (+60% to USD228M, +27% to 150,200 tonnes), Cameroon (+19% to USD160M, +21% to 162,200 tonnes), Republic of Congo (+6% to USD63M, +12% to 68,100 tonnes), and Cote d’Ivoire (+15% to USD37M, +7% to 28,700 tonnes). While import value from Malaysia increased 24% to USD267M, import quantity was flat at 101,000 tonnes. Import value from India increased 7% to USD268M but import volume fell 7% to 63,300 tonnes during the seven month period (Chart 4).

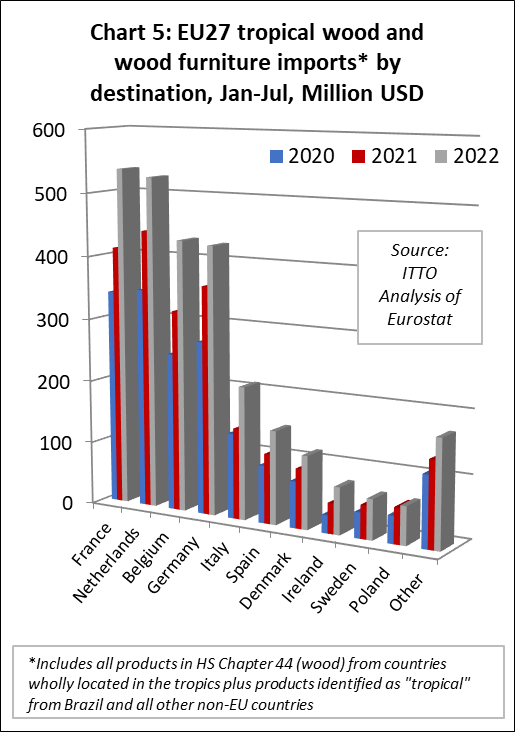

EU27 import value of tropical wood and wood furniture in the first seven months this year increased into all the leading EU destinations for these products, while import quantity increased into all destinations except Germany. Trends into the main import destinations were: France (+30% to USD537M, +8% to 233,100 tonnes); Netherlands (+19% to USD526M, +9% to 204,800 tonnes); Belgium (+35% to USD431M, +18% to 287,800 tonnes); Germany (+17% to USD426M, -1% to 120,100 tonnes); Italy (+47% to USD211M, +44% to 112,400 tonnes); Spain (+34% to USD148M, +35% to 62,700 tonnes); and Denmark (+23% to USD116M, +11% to 28,600 tonnes) (Chart 5).

Sharp deterioration in European economic indicators

The latest eurozone economic update by ING Group, the Dutch multinational banking and financial services corporation, reports that “after a deceleration in economic growth over the summer months, eurozone indicators strongly deteriorated in September, suggesting the start of a recession. The challenges that the eurozone economy has been facing over the last few months have not disappeared. If anything, they have got worse”.

The ING Group particularly highlight the impact of the war in Ukraine on energy prices in Europe and the effects of this on the wider economy: “natural gas exports from Russia to the European Union have been cut further and the sabotage of the Nord Stream 1 and 2 pipelines has created some fears regarding the safety of the gas pipelines from Norway. Unfortunately, according to the latest weather analyses, the risk of a cold winter has risen”.

With mounting concerns on the supply side, ING Group “continue to expect very tight natural gas markets over the winter months, keeping prices at uncomfortably high levels. Moreover, because of the lack of natural gas imports from Russia, prices are not likely to fall significantly in 2023. This will hurt the supply side of the economy, with a growing number of European companies reducing production. And while governments have stepped up their support for households and businesses, we still believe that consumption will contract. At the same time, increasingly tight financial conditions are another headwind for growth”.

ING Group go on to suggest that “while the deceleration of economic activity seemed to be limited during the holiday season, the September data now clearly screams recession”. They point to the latest figures from the S&P Global Eurozone Composite Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) which stood at 48.2 in September, well below the 50 boom-or-bust-level. According to ING Group “With inventories building on the back of slowing sales, eurozone manufacturers reduced their purchases of inputs for the third month in a row. Consumer confidence fell in September to the lowest level since the survey started, with households especially worried about their financial situation over the next 12 months”.

ING Group note that the eurozone inflation rate rose to 10% in September. Energy prices were the main culprit, but core inflation excluding energy also rose to 4.8%. The European Central Bank is therefore expected to become more aggressive in raising interest rates. ING Group are forecasting a 75bp hike in October, followed by 50bp in December and 25bp in February 2023, bringing the deposit rate to 2.25%. ING Group forecast a small negative GDP growth figure for the eurozone in the third quarter of 2022 and a deeper downturn over the winter months. For next year, ING Group anticipate a 0.8% GDP contraction, after a 2.9% expansion in 2022.

Being particularly sensitive to changes in mortgage interest rates – and following a big short-term boost to activity in the immediate aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic – the downturn in the eurozone construction sector is expected to be even larger than in the wider economy. The S&P Global Eurozone Construction Total Activity Index was well below the no-change mark of 50.0 for the fifth successive month in September, at 45.3. The figure for Germany, at 41.8, was particularly low. The figures for Italy (46.7) and France (49.1) were closer to neutral territory.

Broken down by sector, the S&P Index showed that housing activity in the Eurozone during September fell at the fastest rate since May 2020. The fall in the Index was less dramatic for civil engineering and commercial activity, but still below the no-change mark. New orders placed with eurozone construction companies declined for the sixth successive month in September and the rate of contraction quickened for the fifth month running to the sharpest since May 2020. Data broken down by country showed that a much a steeper reduction in Germany drove the overall acceleration, offsetting softer falls in both France and Italy.

September data revealed a worsening degree of pessimism among eurozone construction companies regarding the year-ahead outlook for business activity. Companies were at their most downbeat since the first COVID-19 lockdown in April 2020, reflecting the growing risk of recession in the wider economy. German construction firms were at their most pessimistic since March 2020, while their French counterparts were less downbeat than in August and Italian firms were modestly optimistic.

Commenting on the latest results, Trevor Balchin, Economics Director at S&P Global Market Intelligence, said: “September data rounded off a very weak third quarter for the eurozone construction sector. Outside of the pandemic, the rate of decline in activity in the third quarter was the strongest since the fourth quarter of 2014. Activity fell sharply again in September, with Germany posting a notably steep rate of contraction. The overall pace of decline eased due to slower falls in France and Italy, although this masked a worsening outlook as both new orders and firms’ 12-month expectations sank deeper into negative territory”.

European Parliament and Council start joint negotiations on new deforestation law

On 13 September 2022, the European Parliament adopted its position (the “Parliament Position”) regarding the Proposal for a Regulation on Deforestation-Free Products (the “Proposal”), published by the European Commission on 11 November 2021. The Council of the EU had adopted its general approach on the Proposal on 28 June 2022 (the “Council Approach”).

The first Trilogue for the regulation was held in the last week of September. Trilogues are informal tripartite meetings on legislative proposals between representatives of the Parliament, the Council and the Commission. Their purpose is to reach a provisional agreement on a text acceptable to both the Council and the Parliament. The EU hope to reach political agreement on the Proposal before the COP15 on Biodiversity in December in Montreal. Trilogues are an informal procedure with no pre-set timeline, but the process typically averages 3 to 6 months.

Once political agreement between the Parliament and Council has been reached, the agreed text would still need to be formally endorsed by both legislative bodies, the timing dependent on political urgency and other factors. Once adopted, the main obligations imposed by the Proposal would then apply 12 months (or 18 months as per the Council Approach) from its entry into force, except for microenterprises (and for SMEs as per the Parliament Position) for which it would only apply 24 months after the entry into force.

The three versions of the law on which the Trilogue negotiations are based are available as follows:

- Commission Proposal of 11 November 2021: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/document/download/5f1b726e-d7c4-4c51-a75c-3f1ac41eb1f8_en?filename=COM_2021_706_1_EN_ACT_part1_v6.pdf

- European Council Approach adopted 28 June 2022: https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-10284-2022-INIT/en/pdf

- European Parliament Position adopted 13 September 2022: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2022-0311_EN.pdf

Although the EU institutions are broadly aligned on overall approach and objectives, the Parliament and the Council have suggested a number of changes to the Proposal. The Parliament, in particular, wants an enlarged scope of application (which would include financial institutions) and an extended range of penalties. A recent independent comparison of the three positions by Linklaters, an international law firm, is available at:

https://sustainablefutures.linklaters.com/post/102hydp/eu-deforestation-proposal-next-steps

A new independent analysis of the implications of the law for the tropical timber trade by Alain Karsenty Fondation pour la Nature et l’Homme is available:

- In French: https://www.fnh.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/TT-contribution-deforestation.pdf

- In English: https://www.atibt.org/files/upload/news/EU_REGULATION/The_draft_European_regulation_on_imported_deforestation.pdf

Recent timber trade and industry comments on the law include:

- Open Letter of 7 September 2022 from CEI-Bois, EOS, ETTF and ATIBT: https://www.cei-bois.org/_files/ugd/5b1bdc_9f34319605d844ec8fe606682f90f14d.pdf

- Considerations of the European forest-based industries on the proposal for a regulation on deforestation and forest degradation adopted by the European Parliament signed by some of the leading European forest products industry associations: https://www.cei-bois.org/_files/ugd/5b1bdc_bb2d941402734f90b3883eb1f12387ca.pdf

Independent press commentary on the legislation, including free access to an on-line event at which representatives from the commercial food and agriculture sectors, academics and NGOs discuss some of the wider implications of the legislation, is available at:

- https://www.foodnavigator.com/Article/2022/10/07/do-due-diligence-laws-actually-promote-climate-smart-food

- https://www.foodnavigator.com/Article/2022/08/25/due-diligence-obligations-a-golden-opportunity-for-transparent-supply-chains-or-a-costly-administrative-nightmare

European Parliament wants new FLEGT VPAs with additional partners

There is only passing reference in these various commentaries to the future role of the existing FLEGT VPA process and licenses in the prospective EU deforestation-free regulatory framework. More insight is gained from review of the three versions of the law now being considered. The European Parliament Position would suggest a larger long-term role for the existing FLEGT VPA framework than implied in the original legislative proposal or Council Approach.

Both the original Commission Proposal and the Council Approach note that the EU Fitness Check of the FLEGT regulation and EUTR had determined that “while the legislation has had a positive impact on forest governance, the objectives of the two Regulations – namely to curb illegal logging and related trade, and to reduce the consumption of illegally harvested timber in the EU – have not been met”.

Both the original Proposal and the Council Approach also state that “To respect bilateral commitments that the European Union has entered into and to preserve the progress achieved with partner countries that have an operating system in place (FLEGT licensing stage), this Regulation should include a provision declaring wood and wood-based products covered by a valid FLEGT license as fulfilling the legality requirement under this Regulation.”

There is no provision in either text for the FLEGT licenses developed under the existing VPAs to fulfil either the deforestation-free or forest degradation-free requirement under the regulation. Instead there is a reference to a new form of partnership with producer countries “to jointly address deforestation and forest degradation”.

These new partnerships “will focus on the conservation, restoration and sustainable use of forests, deforestation, forest degradation and the transition to sustainable commodity production, consumption processing and trade methods”. They may include “structured dialogues, support programmes and actions, administrative arrangements and provisions in existing agreements or agreements that enable producer countries to make the transition to an agricultural production that facilitates the compliance of relevant commodities and products with the requirements of this regulation”.

Unlike the FLEGT VPAs, there is no expectation in the original Proposal or the Council Approach that these partnerships should lead to “licensing” of products explicitly to ensure compliance with the EU’s deforestation-free legislation. Instead, the agreements and their effective implementation would be taken into account when countries and sub-national jurisdictions are benchmarked by the European Commission into three risk categories; “High risk”, “Low risk”, and “Standard risk”. For products from “low risk” countries or subnational jurisdictions operators would apply a “simplified due diligence”. Competent authorities would apply enhanced scrutiny on relevant products from “high risk” countries or subnational jurisdictions.

While the Parliament Position adopts much the same approach, it is notable for containing a more nuanced analysis of the value of the FLEGT process. On the EUTR and FLEGT VPA legislation, the Parliament Position is that “the performance and implementation of the two Regulations underwent a fitness check which found that, while both achieved some success, a number of implementation challenges have held back progress towards achieving fully their objectives. The application and functioning of the due diligence scheme under [the EUTR] on the one hand, and the limited number of countries involved in the VPA process, with only one having thus far an operating licensing system in place (Indonesia), on the other, curtailed effectiveness in meeting the objective of consumption of illegally harvested timber in the EU”.

The Parliament Position also goes into more detail on the purpose of the VPAs and envisages a continuing role for FLEGT licensing. It notes that “VPAs are intended to foster systemic changes in the forestry sector aimed at sustainable management of forests, eradicating illegal logging and supporting worldwide efforts to stop deforestation. VPAs provide an important legal framework for both the Union and its partner countries, made possible with the good cooperation and engagement by the countries concerned. New VPAs with additional partners should be promoted”.

The Parliament Position also states that other partners should be encouraged to work towards reaching the FLEGT Licensing stage and that the “VPA partnerships should be supported with adequate resources and specific administrative and capacity building support”.

The Parliament Position is also more expansive on the content of the new partnerships proposing that they “shall ensure that indigenous peoples, local communities and civil society, are involved in the development of joint roadmaps” which “shall be based on milestones agreed with local stakeholders”.

The Parliament Position is that the Commission should “particularly engage with producing countries to remove legal obstacles to their compliance, including national land tenure governance and data protection law”, and that partnerships should be “with countries and parts thereof identified as high-risk, to support their continuous improvement towards the standard risk category”.

The Parliament Position also emphasises that the new partnerships should “pay particular attention to smallholders in order to enable these smallholders to transition to sustainable farming and forestry practices and to comply with the requirements of this Regulation, including through enabling sufficient and user friendly information”. Specifically, that “adequate financial resources shall be available to meet the needs of smallholders”.

In conclusion, there does appear to be a consensus across the EU legislature that FLEGT Licenses issued under the existing VPA framework should only fulfil the legislative requirement but not the deforestation-free or forest degradation-free requirement of the new deforestation law. However, the Parliament foresees continuing support for the FLEGT VPAs and licensing process as an important mechanism to facilitate easier conformance of timber products with the new regulation.

In contrast, the original Proposal and Council Approach implies that the EU should prioritise new broader forest partnerships that cover all forest risk commodities and that are not focused on licensing. Clarity on the long-term role of the existing VPAs and of FLEGT licensing, and on the relationship between the existing VPAs and new forest partnerships, will only emerge once the on-going Trilogue negotiations are concluded and a final text of the new deforestation law is agreed.