The latest data from the UK Office for National Statistics shows that UK GDP increased 4.0% in 2022 after 7.6% growth in 2021, as it recovered from the historic blow from the COVID-19 pandemic. However this “rise” over the last two years must be considered in the light of the UK being amongst countries worst affected by the COVID-19 pandemic which led to a 9.4% fall in GDP in 2020 at a time when there was already uncertainty due to the country’s departure from the EU. The UK economy in December 2022 was still smaller than it was in December 2019.

UK Tropical Wood & Wood Furniture 2004 to 2022

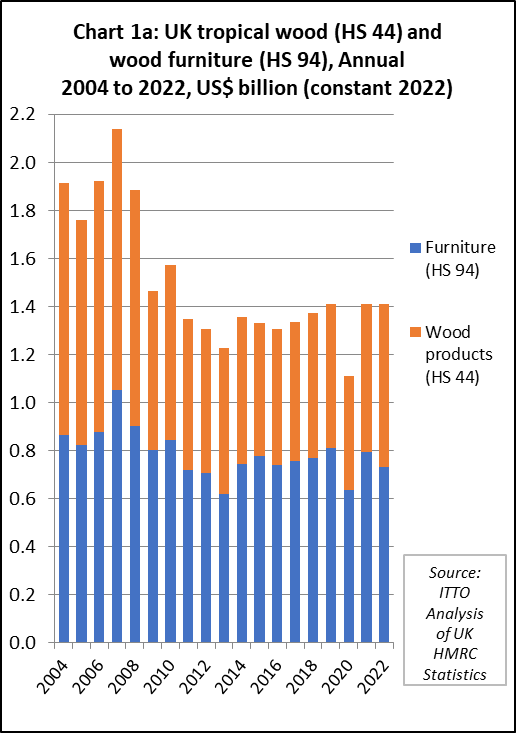

The relatively sluggish recovery of the UK economy last year is reflected in UK imports of tropical wood and wood furniture products which were flat overall in 2022, valued at US$1.4 billion, the same as the previous year and just equalling the pre-COVID level in 2019. UK import value of tropical wood and wood furniture products last year was only marginally above the long term average for the previous ten years and well below levels prevailing in the years prior to 2010 (Chart 1a).

Strong UK imports of tropical products in the first half of last year were offset by a sharp downturn in the last six months of the year. In 2022 there was an increase in UK import value of tropical joinery (+9% to US$271 million), sawnwood (+32% to US$124 million), and mouldings/decking (+18% to US$35 million). However UK import value of tropical wood furniture fell 8% to US$731 million, while import value of tropical hardwood plywood was down 12% to US$168 million.

Vietnam was the leading supplier of tropical wood and wood furniture to the UK last year, with import value of US$382 million, 3% down on the previous year. The value of direct imports also declined last year from all three of the other leading tropical suppliers including Indonesia (-8% to US$309 million), Malaysia (-4% to US$238 million), and India (-3% to US$102 million). However, these figures may overestimate the decline as problems of shipping cargo directly from Asia into the UK last year contributed to an 63% increase in the value of tropical wood and wood furniture imports into the UK from EU27 countries, to US$107 million.

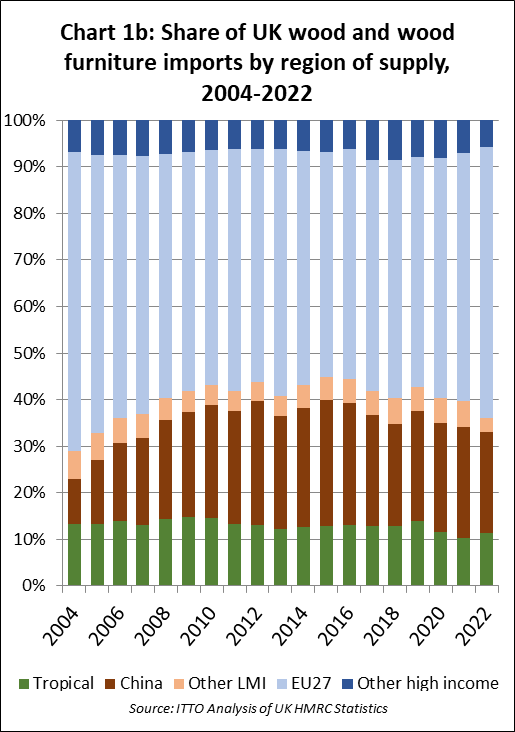

Share of UK Wood & Wood Furniture Imports by Region of Supply

After losing share in the UK market between 2019 and 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic, tropical wood and wood furniture products regained some share last year, mainly at the expense of other lower and middle income (LMI) countries, particularly China, Russia, and Belarus. The total value of UK imports of wood and wood furniture products from all countries was US$13.62 billion in 2022, 9% less than the previous year. This followed a gain of 42% in 2021. The share of tropical products in total UK wood and wood furniture import value increased from 10.4% in 2021 to 11.4% last year, although this is still well below the long term average of between 13% and 14% share (Chart 1b) .

UK import value of non-tropical wood and wood furniture products from China fell 17% to US$2.67 billion last year. The share of China in total UK wood and wood furniture imports fell from 24% in 2021 to 22% last year. This represents a return to more normal levels in UK imports from China after a 43% surge in US$ value the previous year in response to booming demand in the immediate aftermath of the COVID lockdowns. Other factors contributing to slower UK imports from China last year included supply problems during China’s strict COVID-19 lockdowns, serious congestion at UK ports in the first half of last year, and concerns that Chinese products may contain Russian wood which has been subject to trade sanctions in the UK since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February last year.

UK sanctions imposed on Russian products led to an 89% decline in the value of UK imports of Russian wood and wood furniture last year, from US$329 million to just $36 million. Although the UK has not officially sanctioned imports of wood from Belarus, these also fell sharply, by 90% from US$59 million to US$6 million. Imports of non-tropical products from several other LMI countries also fell sharply last year including Brazil (-19% to US$151 million), South Africa (-37% to US$29 million), Ukraine (-14% to US$26 million), UAE (-56% to US$17 million), and Uruguay (-29% to US$16 million). Overall the share of UK imports of non-tropical products from LMI countries other than China decreased from 6% to 3% last year.

UK imports of non-tropical wood and wood furniture products from the EU27 fell 1% to US$7.17 billion in 2022. This followed on from a huge 46% increase in 2021. And because the decline from the EU27 last year was much less than from other regions, the EU27 total share of UK import value of wood and furniture from the EU27 increased from 53% in 2021 to 58% in 2022.

Expectations that the UK’s departure from the EU might lead to a decrease in the share of imports of wood and wood furniture from the EU and a switch to other regions have yet to be realised. On the contrary, in the five years following the UK’s decision to trigger Article 50 of the EU Treaty on 29 March 2017 which began the formal process for withdrawal from the EU, a process eventually completed in January 2020, the share of UK wood and wood furniture imports from the EU27 has risen by nearly 10%.

UK Monthly Imports of Wood & Wood Furniture by Region of Supply

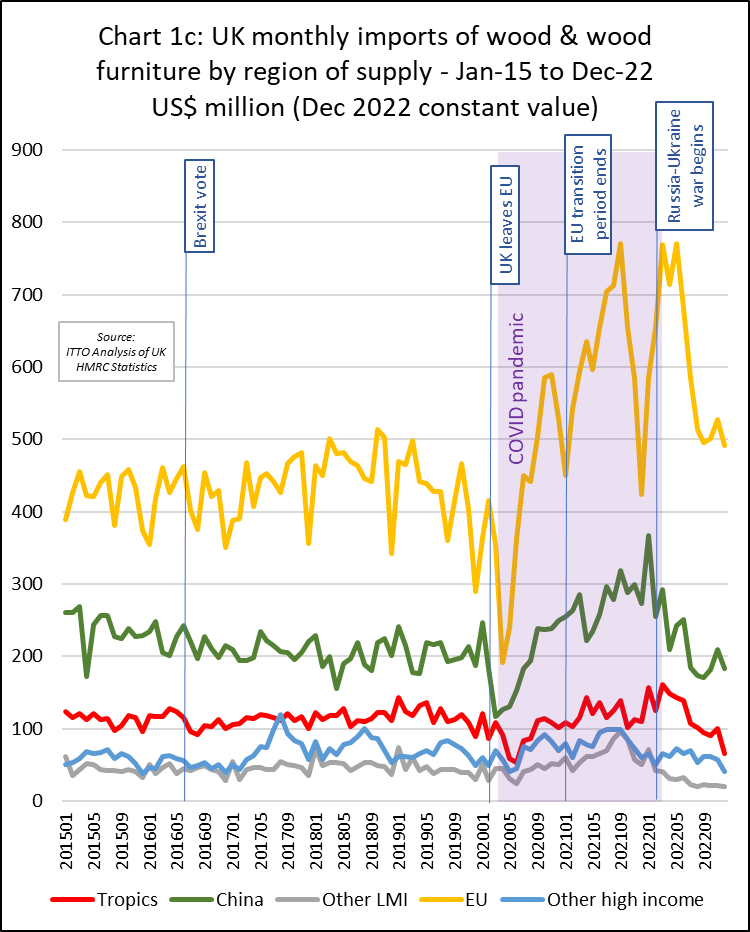

Of course recent trends in UK wood and wood furniture imports have probably been influenced much more by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic than by Brexit. And since the start of last year, trading patterns in all parts of Europe have also been impacted by the war in Ukraine. Therefore these short-term changes in market share may not be a good guide to the long term effects of Brexit. Probably the most notable feature of UK imports in recent years has been the extraordinary level of volatility. This is highlighted in Chart 1c which tracks UK import value of all wood and wood furniture by major region of supply on a monthly basis since January 2015.

The level of UK trade volatility began to increase soon after the Brexit vote in June 2015, an event which created considerable economic uncertainty, compounded by regular and often confusing alterations to the timetable for the UK’s departure from the EU, and the lack of clarity on the trade deal with the EU that would eventually result.

And then just a few weeks after the UK officially left the EU on 31 January 2020 – with a “harder” Brexit deal than many expected – the COVID pandemic struck leading to a very sharp dip in trade during the first lockdown. But this was followed by a massive and unexpected rebound in trade, initially as money was poured into home renovation projects, and then as government stimulus measures, much focused on the construction sector, began to kick in. These measures helped maintain a buoyant level of trade until the middle of last year.

The combination of COVID and Brexit meant that problems of shipping and transport logistics were particularly severe in the UK between 2020 and 2022. The problems of shipping into the UK led to more calls for distributors and manufacturers to shift away from their existing “just-in-time” business model to a “just-in-case” model of bringing more manufacturing closer to home and increasing inventories once again. In practice, this implied a continuing high level of dependence on the large suppliers in continental Europe for which turnaround times, while much longer than before the UK left the EU single market, still compared favourably to imports from other parts of the world.

What happens next is uncertain. However, the current economic situation in the UK implies that overall demand, and the level of trade, will be subdued during 2023. In early February, the Bank of England forecast that the UK would enter a shallow but lengthy recession, starting in the first quarter of this year and lasting five quarters. UK business groups have said that future investment will be deterred by a steep increase in taxation on profits that takes effect in April. Retailers are reported to be cutting inventory levels due to reduced consumer demand. Inflation remains high and interest rates are being raised, increasing the costs of borrowing.

Despite Brexit, EU-based wood suppliers seem certain to maintain their dominance in the UK market for many years to come, not least due to their proximity and that they are particularly well placed to supply the commodity softwoods and mass-produced furniture on which the UK relies. But, equally, opportunities for non-EU wood product suppliers, including in the tropics, should improve around the margins of the UK market with the recent dramatic fall in global freight rates and as the logistical problems that built up during the pandemic have now eased considerably. One indicator is the Drewry global freight rate index which at $1,997 per 40-foot container in January was 81% below the peak of $10,377 reached in September 2021 and was 26% lower than the 10-year average of $2,693, indicating a return to more normal prices.