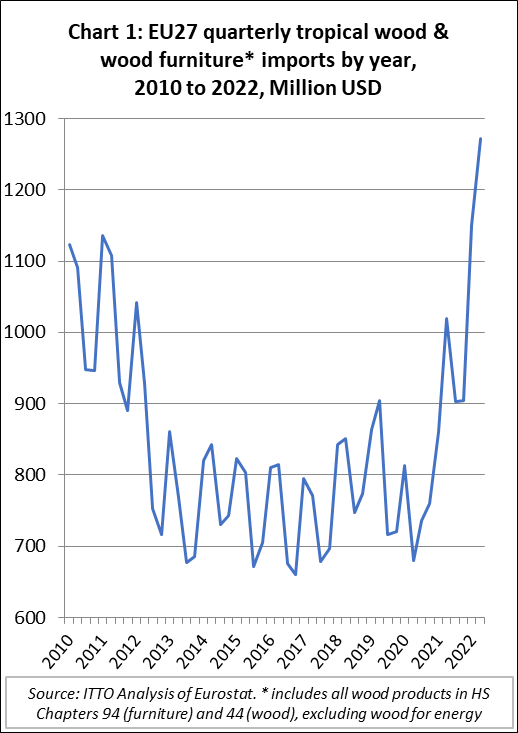

Between April and June this year, EU27 import value of tropical wood and wood furniture products was, in dollar terms, at the highest quarterly level since at least before the 2007-2008 financial crisis (Chart 1). Imports of USD1.27B during the second quarter of 2022 were 11% more than the previous quarter and 25% more than the same quarter the previous year.

In the first six months of this year, import value of tropical wood and wood furniture totalled USD2.42B, a gain of 29% compared to the same period last year. Part of the gain in EU27 tropical wood product import value was due to a rise in CIF prices. This was driven by the combination of a sharp fall in the value of the euro against the dollar, continuing high freight rates, and severe shortages of wood and other materials. In quantity terms, EU imports of tropical wood and wood furniture products in the first six months of this year were, at 1,025,300 tonnes, up 15% compared to the same period in 2021.

Since the start of this year, the euro value has declined around 10% against the US dollar and is currently at the lowest level for 20 years. In mid-July, the euro hit parity with the US currency for the first time since 2002. The euro’s slide underlines the foreboding in the 19 European countries using the currency as they struggle with an energy crisis caused by Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Usually such a sharp decline in the value of the European currency would lead to a reduction in imports as prices for goods from outside the EU escalated. However, this time it is different as importers and manufacturers are struggling in the face of critical wood supply shortages brought on by the lingering effects of the global pandemic and the more recent impact of the war in Ukraine. Importers have been more willing to follow the prices upwards than in previous periods of currency weakness.

The curtailment of wood supplies from Russia and Belarus due to the sanctions imposed by the EU following the invasion of Ukraine in February is opening up new opportunities in the EU market for some tropical wood products, notably plywood and decking for which Russian birch and larch products have been important substitutes.

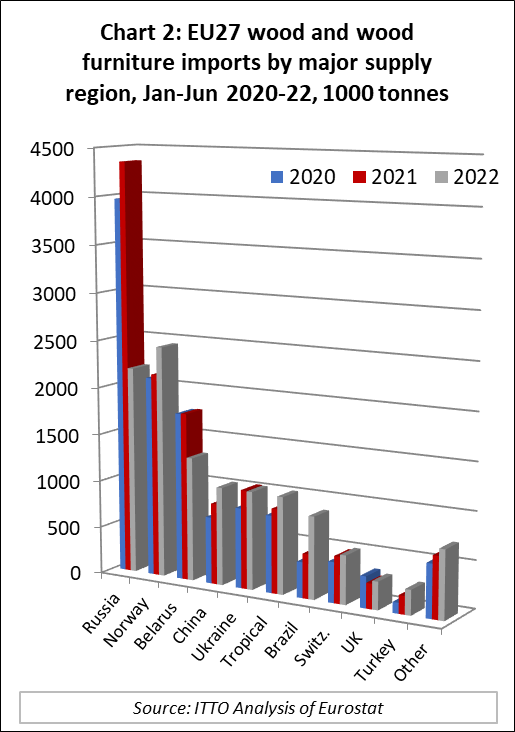

In the first six months of this year, tropical products accounted for 8.8% of the quantity of all wood and wood furniture products imported into the EU27, which compares to 6.8% during the same period in both 2021 and 2020. The gain in tropical wood share is due mainly to a large reduction in imports from Russia (-50% to 2.19 million tonnes) and Belarus (-26% to 1.31 million tonnes) during this period. After an initial fall in the early months of the war, EU27 imports from Ukraine recovered some ground in the second quarter and by the end of the first six months of this year were, at 1.03 million tonnes, only 1% down on the same period in 2021 (Chart 2).

While tropical wood has made gains in the EU market this year, the largest beneficiaries of the opening supply gap due to the fall in imports from Russia and Belarus have been non-tropical wood products from Norway (+14% to USD2.45B), China (+21% to USD1.03B), Brazil (+86% to USD867M), Turkey (+37% to USD263M), Chile (+52% to USD54M), New Zealand (+31% to USD31M), Uruguay (+242% to USD23M), and South Africa (+154% to USD8M).

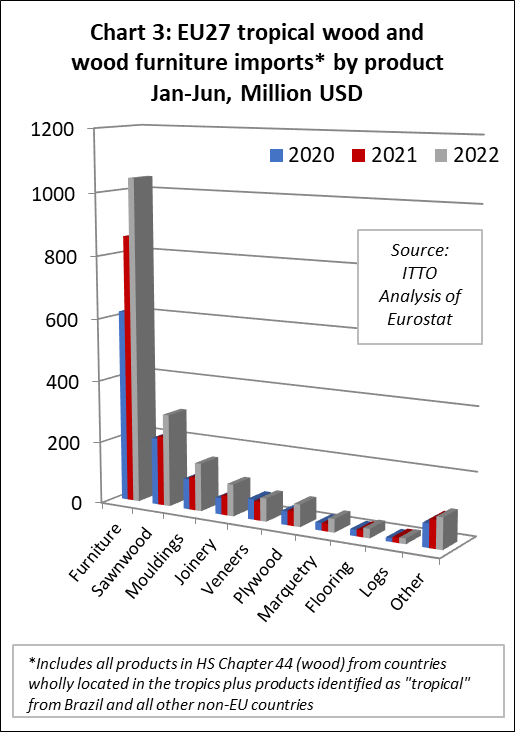

Rise in EU27 import value across all tropical wood product groups

Nevertheless, there were significant increases in the value of EU27 imports of most wood product groups from tropical countries in the first six months of this year (Chart 3). For wood furniture, import value of USD1043M during the January to June period was 22% more than the same period last year. For tropical sawnwood, import value of USD467M was 30% up on the same period last year. Import value of tropical mouldings/decking was USD235M in the first six months of this year, a gain of 40% compared to the same period in 2021.

There were also large gains in the value of EU27 imports of tropical joinery products (+49% to USD155M), tropical veneer (+24% to USD119M), plywood (+62% to USD118M), marquetry (+70% to USD63M) and flooring (+31% to USD43M) in the first six months of this year. Import value of tropical logs was USD31M between January and June, 22% more than the same period last year.

EU27 import value of tropical furniture rises despite fall in quantity

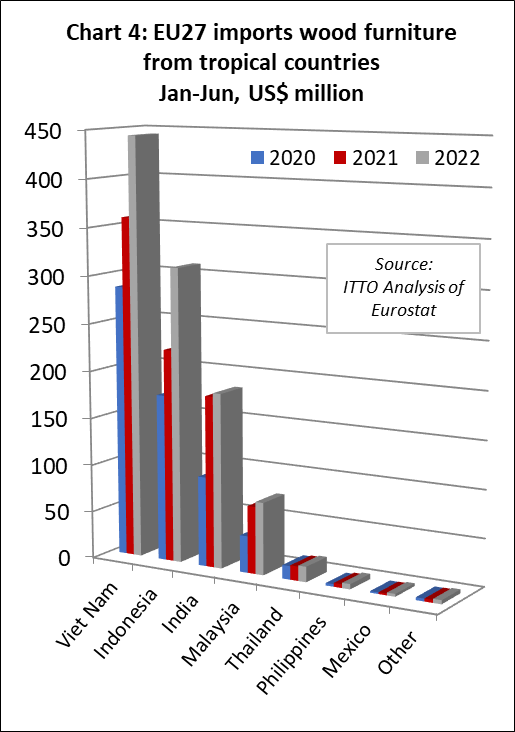

In the first six months of 2022, EU27 import value of wood furniture from tropical countries was USD1043M, 22% higher than the same period in 2021. However, in the case of furniture, the increase in dollar value is entirely due to the rise in freight rates and prices and the weakness of the euro rather than an increase in export quantity. In tonnage terms, imports actually declined 3% to 211,000 tonnes during the six month period.

In the first half of 2022, there were particularly large increases in EU27 wood furniture import value from Vietnam (+24% to USD444M) and Indonesia (+38% to USD311M). More moderate gains were made in import value from India (+2% to USD184M), Malaysia (+8% to USD76M), Thailand (+7% to USD16M) and the Philippines (+36% to USD6M). EU27 wood furniture imports from all other tropical countries are negligible (Chart 4).

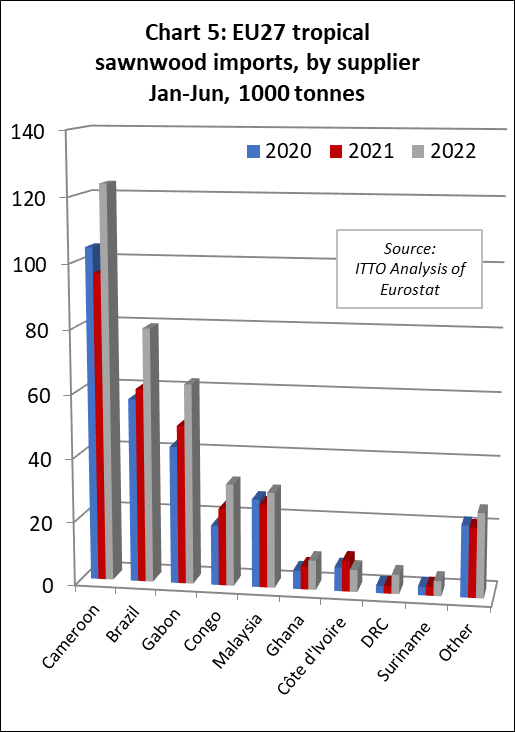

EU27 imports of tropical sawnwood up 27%

After two slow years during the global pandemic, EU27 imports of tropical sawnwood have recovered ground this year. Imports of 382,000 tonnes in the first six months were 27% higher than the same period in 2021 and 31% more than the same period in 2020.

Sawnwood imports increased sharply in the first six months of this year from all the largest tropical suppliers to the EU27 including Cameroon (+28% to 123,700 tonnes), Brazil (+31% to 79,800 tonnes), Gabon (+26% to 62,800 tonnes), Congo (+32% to 32,100 tonnes) and Malaysia (+15% to 30,000 tonnes). Of smaller supply countries, there were large percentage increases in imports from Ghana (+28% to 9,200 tonnes), DRC (+154% to 6,100 tonnes), Suriname (+68% to 4,700 tonnes), Indonesia (+56% to 3,900 tonnes), Angola (+40% to 3,200 tonnes), Peru (+18% to 2,700 tonnes), and CAR (+307% to 2,000 tonnes). In contrast imports from Côte d’Ivoire fell 29% decline to 7,000 tonnes (Chart 5).

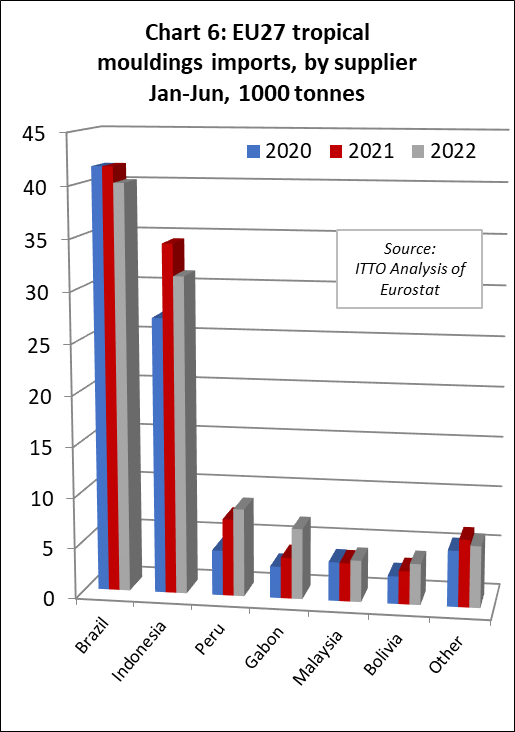

Unlike sawnwood, EU27 imports of tropical mouldings/decking were quite slow in the first half of this year, most likely due to supply shortages rather than to limited demand. Imports of 101,300 tonnes between January and June this year were at the same level as the same period last year. Falling imports from the two largest supply countries, Indonesia (-9% to 31,300 tonnes) and Brazil (-4% to 40,100 tonnes), were offset by rising imports from Peru (+14% to 8,700 tonnes), Gabon (+72% to 7,000 tonnes), Bolivia (+23% to 4,100 tonnes), and Malaysia (+8% to 4,100 tonnes) (Chart 6).

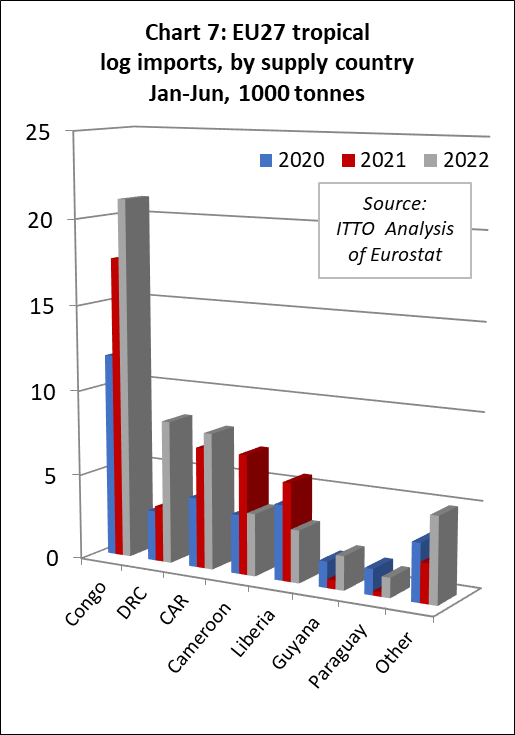

In the first six months of 2022, the EU27 imported 52,300 tonnes of tropical logs, 19% more than the same period in 2021. EU27 log imports increased from all three of the largest African supply countries in the first six months of this year compared to the same period last year; Congo (+20% to 21,100 tonnes), DRC (+157 to 8,400 tonnes), and CAR (+13% to 8,000 tonnes). Imports also increased sharply from negligible levels last year from two South American countries, Guyana (+281% to 2,000 tonnes) and Paraguay (+343% to 1,200 tonnes). However, log imports were down 48% to 3,600 tonnes from Cameroon and down 46% to 3,100 from Liberia.

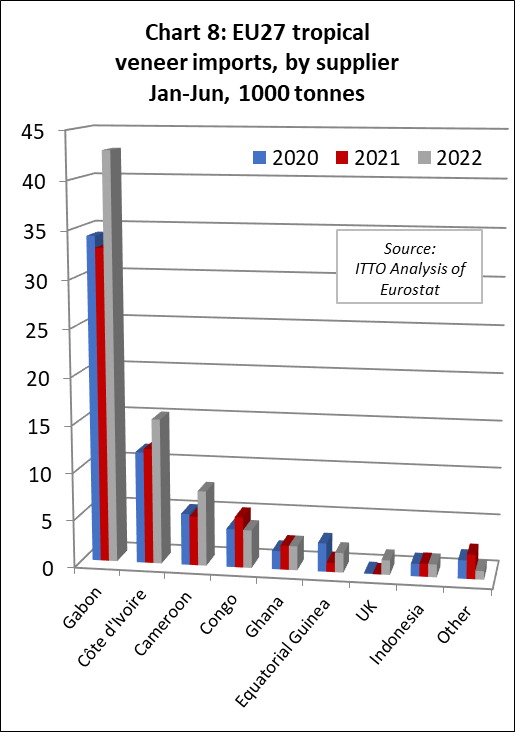

Gabon drives rebound in EU27 imports of tropical veneer and plywood

In the first six months of 2022, the EU27 imported 78,500 tonnes of tropical veneer, 24% more than the same period last year. Imports of tropical veneer from Gabon, by far the largest supplier to the EU27, increased 30% to 42,900 tonnes. There were also large gains in imports from Côte d’Ivoire (+26% to 15,300 tonnes), Cameroon (+53% to 7,900 tonnes) and Equatorial Guinea (+111% to 2,100 tonnes). After virtually no indirect trade in tropical veneer to the EU27 via the UK last year, this trade totalled 1,500 tonnes in the first six months of 2022. These gains in EU27 tropical veneer imports were partly offset by a 25% decline in imports from Congo to 4,000 tonnes (Chart 8).

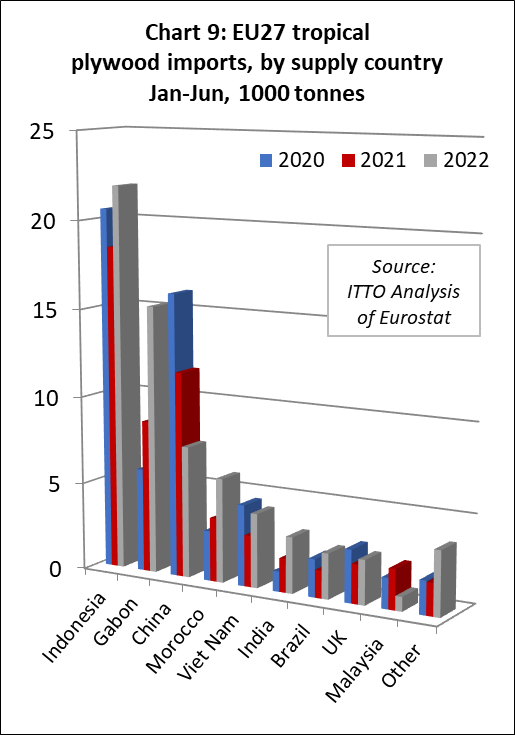

In the first six months of 2022, EU27 tropical plywood imports of 67,600 tonnes were 23% more than the same period the previous year. Imports from Indonesia, at 21,900 tonnes, were up 19% compared to the same period last year. However, the biggest percentage increase was in imports from Gabon, rising 76% to 15,300 tonnes. Imports of tropical plywood also increased from Morocco (+64% to 5,900 tonnes), Vietnam (+44% to 4,200 tonnes), India (+66% to 3,200), Brazil (+65% to 2,600 tonnes) and the UK (+15% to 2,100 tonnes). These gains offset a 36% decline in imports of tropical hardwood faced plywood from China to 7,500 tonnes, and a 64% fall in imports from Malaysia to just 800 tonnes (Chart 9).

Rise in EU27 imports of tropical flooring from Malaysia continues

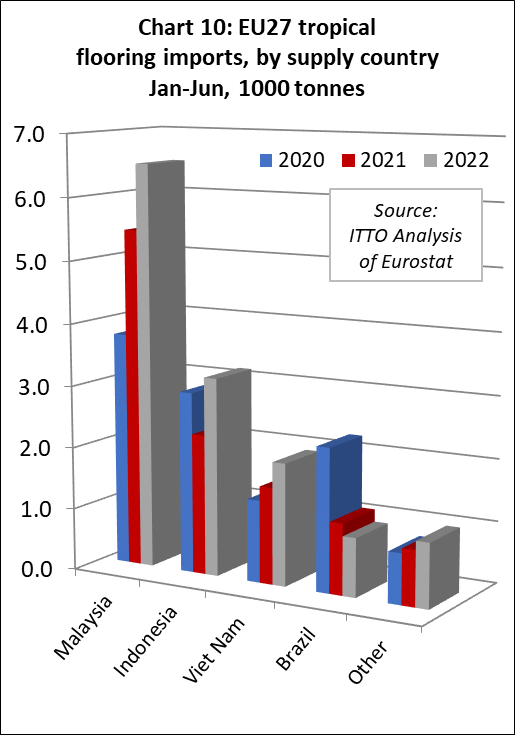

In the first six months of 2022, the EU27 imported 13,700 tonnes of tropical wood flooring, 21% more than the same period in 2021. The rise in EU27 wood flooring imports from Malaysia, that began in 2020, has continued this year. Imports of 6,500 tonnes from Malaysia in the first six months of 2022 were 19% more than the same period in 2021. There were also large gains, from a smaller base, from Indonesia (+41% to 3,200 tonnes) and Vietnam (+27% to 2,000 tonnes). However flooring imports from Brazil have continued to slide this year, at just 900 tonnes in the first six months, 17% down compared to the same period last year (Chart 10).

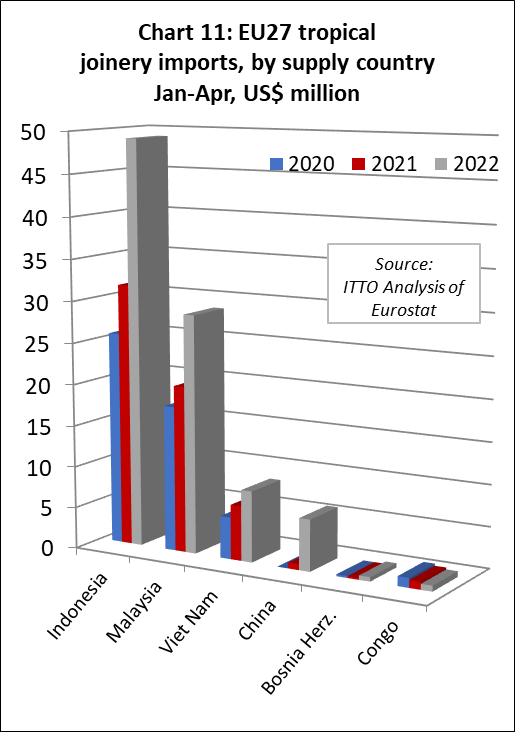

The dollar value of EU27 imports of other joinery products from tropical countries – which mainly comprise laminated window scantlings, kitchen tops and wood doors – increased 49% to USD155M in the first six months of 2022. Import value increased 38% to USD71M million from Indonesia, 49% to USD45M from Malaysia, and 45% to USD15M from Vietnam. The apparent large increase in imports of this commodity group from China, from negligible levels to USD9M in the first six months of this year, is due to a change in product codes from the start of this year allowing more joinery products manufactured using tropical hardwood in non-tropical countries to be separately identified (Chart 11).

Unlike for furniture, the rise in import value for joinery this year was not driven entirely by rising prices but was also indicative of an increase in import quantity. In quantity terms, the EU27 imported 58,300 tonnes of tropical joinery products in the first six months of this year, 35% more than the same period last year.

European Parliament Committee near unanimous on deforestation law

On 12 July 2022, the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety Committee of the European Parliament adopted its position with 60 votes to 2 and 13 abstentions on the Commission proposal for a regulation on deforestation-free products to halt EU-driven global deforestation.

The text of the Parliamentary Committee position, with their recommendations for amendments to the text proposed by the European Council in November last year, can be downloaded at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-9-2022-0219_EN.pdf.

Following near unanimous endorsement by the responsible Parliamentary Committee, Plenary is expected to officially adopt Parliament’s position in September. After that negotiations on the final law will begin with member states.

The negotiation process will aim to agree a final version of the law as a compromise between the Parliamentary text and the text agreed on 28 June by the European Council – which represents the Member States (see ITTO Market Report 1st–15th July 2022, page 29).

According to the European Parliament press release issued on adoption of the Committee’s position, the new law would make it obligatory for companies to verify (so-called “due diligence”) that goods sold in the EU have not been produced on deforested or degraded land. This would assure consumers that the products they buy do not contribute to the destruction of forests outside the EU and hence reduce the EU’s contribution to climate change and biodiversity loss globally.

European MEPs also want companies to verify that goods are produced in accordance with human rights protected under international law and the rights of indigenous people in addition to the relevant laws and standards in the country where the products are produced.

The Commission’s proposal covers cattle, cocoa, coffee, palm-oil, soya and wood, including products that contain, have been fed with or have been made using these commodities (such as leather, chocolate and furniture). Parliament wants to include pigmeat, sheep and goats, poultry, maize and rubber, as well as charcoal and printed paper products, and bring the cut-off date one year forward, to 31 December 2019.

The Commission would have to evaluate, no later than two years after the entry into force, whether the rules need to be extended to other goods such as sugar cane, ethanol and mining products, and how feasible this is. MEPs also want them to cover other natural ecosystems such as grasslands, peatlands and wetlands, if deemed appropriate by the Commission, within one year after the entry into force. Finally, MEPs also want financial institutions to be subject to additional requirements to ensure that their activities do not contribute to deforestation.

The European Parliament press release notes that “While no country or commodity will be banned, companies placing products on the EU market would be obliged to exercise due diligence to evaluate risks in their supply chain. They can for example use satellite monitoring tools, field audits, capacity building of suppliers or isotope testing to check where products come from. EU authorities would have access to relevant information, such as geographic coordinates. Anonymised data would be available to the public”.

The press release also states that “Based on a transparent assessment, the Commission would have to classify countries, or part thereof, into low, standard or high risk within six months of entry into force of this regulation. Imports from low risk countries will be subject to fewer obligations”.

American hardwood industry comment on EU deforestation law

The American Hardwood Export Council (AHEC) has issued a statement on the potential implications of the new EU deforestation-free proposal for the US hardwood trade. It is relevant for the tropical trade, firstly because American hardwoods are key direct competitors in tropical hardwoods in a wide range of European wood applications, and secondly because there are close parallels between the supply chains for tropical and American hardwoods, both of which derive primarily from managed semi-natural forest rather than plantations.

Drawing on information on the specific characteristics of these supply chains, the statement raises issues on the practical implications of the “geolocation” requirement specifically for wood sourced from diverse semi-natural forests where forest ownership is highly fragmented. According to the AHEC statement “More than 90% of U.S. hardwood supply derives from low-intensity harvesting of diverse semi-natural forest by non-industrial owners, mainly individuals and families”.

In such circumstances, AHEC suggest that supply of commercial volumes of hardwood of widely different grades, colours and textures requires that wood be aggregated from a large number of smallholders over a lengthy period of time, a process which inevitably involves a lot of mixing from different smallholders.

Although each of these smallholders will generally be within a 25 to 150 mile radius of each mill, a problem arises for American hardwoods because each “geolocation” must refer to a “plot of land” defined in the draft Regulation as “within a single real-estate property”. AHEC notes that “because harvest volumes from each plot of land are so small, a typical hardwood mill needs to purchase logs from as many as several hundred forest owners each year”.

AHEC go on to suggest that “under the current draft legislation, even a small U.S. hardwood mill would likely be under an obligation to provide a list of at least several tens, and probably hundreds, of geolocations to identify the ‘plots of land’ from which wood in each individual consignment might be derived. An exporter operating a concentration yard – purchasing from a range of sawmills and where additional sorts are often made to ensure each customer is supplied with wood of specific species, quality, size, and color – will be required to provide a list of several hundred, perhaps even thousands, of plots of land with each consignment”.

As a result the AHEC statement suggests that “In practice, linking all these geolocations with individual consignments would quickly overwhelm the management systems of even the largest most sophisticated companies, let alone the relatively small, often family-run, enterprises that predominate in the U.S. hardwood sector”.

AHEC contrast this situation with “a large industrial operation, dependent on state concessions or company owned lands, where each ‘plot of land’ extends to thousands of hectares, and each harvest comprises single-aged monocultures. It should be obvious this type of large industrial operation gains a clear competitive advantage from the geolocation requirement as currently set out in the draft EU law”.

AHEC also suggest that “If the regulation is adopted in its current form, the only American hardwood lumber likely to be available to EU buyers will be the around 10% of production from state-owned forest and the few areas of large industry lands. Log exports will be less affected, and in fact will be encouraged at the expense of lumber exports as the need for sorting and grading is much less”.

AHEC believe that this potential issue with the law could be “readily resolved through some minor amendments to the EU’s legal text”, specifically that “rather than linking to a single real estate property, the definition of ‘plot of land’ needs to be adaptable to the wide range of circumstances prevailing in supply of the regulated commodities. For non-industrial forest owners, a suitable definition would be to a specific jurisdiction, co-operative, or community where there is a demonstrably low risk of illegal harvest or deforestation”.

To link specific products with a low risk jurisdiction, AHEC say that they are “currently facilitating development of a new certification framework specifically designed for low-intensity non-industrial hardwood operations. The framework is based on third party assessment of risk at jurisdictional level (individual state in the case of US) in accordance with a ‘Jurisdictional Risk Assessment’ (JRA) standard which will assess specific risk of illegality, deforestation, forest degradation, plus non-conformance to a wider range of sustainable forestry principles”.

According to AHEC, “The certification system links with ideas pioneered in the EU FLEGT initiative to build robust governance at jurisdictional level. It requires and builds on increasingly accessible and good quality forest inventory data. It also links with a World Forest ID project to prepare a comprehensive database of US hardwood samples from across the US for Stable Isotope Ratio Analysis (SIRA). This will allow a regular check of the overall integrity of the system”.

The AHEC statement is available at: