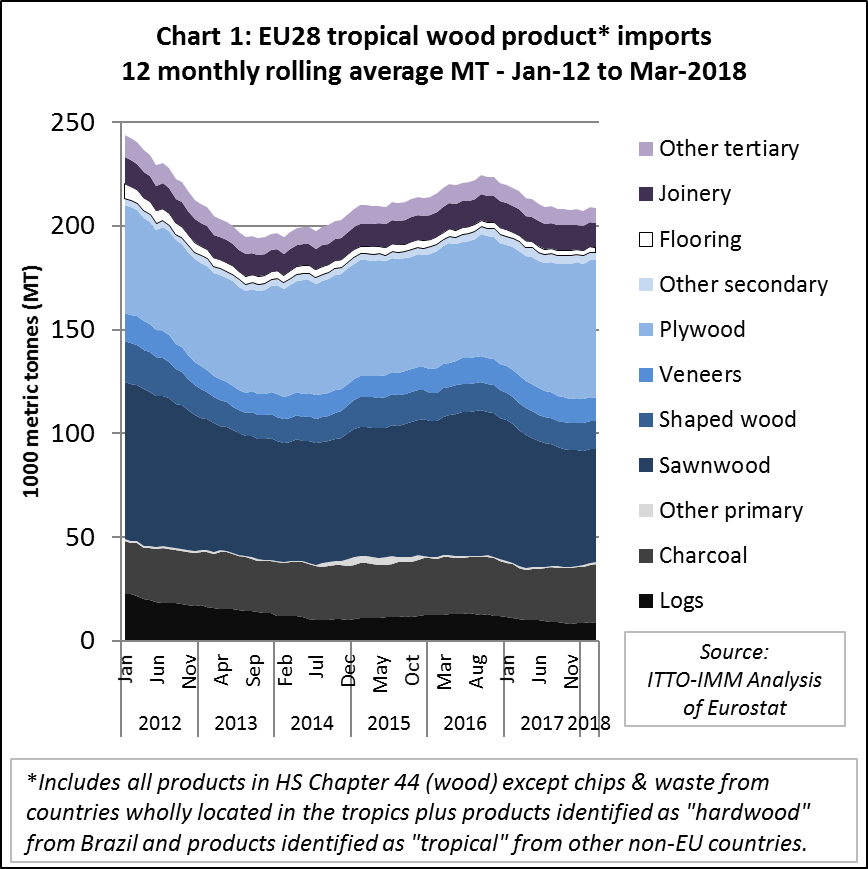

The slowdown in EU imports of tropical products, which began in 2016 and continued throughout last year, levelled off in the first quarter of 2018. Chart 1 shows twelve monthly rolling average imports (to iron out seasonal fluctuations) into the EU of all tropical wood products listed in HS Chapter 44 (excluding wood waste and chips). It shows that imports peaked at an average of 224,000 metric tonnes (MT) per month in September 2016, slipped to a low of 207,000 MT in January this year and recovered only slightly, to 209,000 MT, by March 2018 (Chart 1).

EU imports of tropical wood products in the first quarter of 2018 were only around 7% more than the all-time low of 195,000 MT per month recorded in the middle of 2013 at the height of the euro-zone crises.

In value terms, EU imports of tropical wood products averaged around €203 million per month in the first quarter of 2018, 13% more than the all-time low in 2013 but 6% down on the level prevailing in 2016.

Most of the rise and subsequent slowdown in EU tropical imports in the last three years was driven by sawn wood. The stabilisation of the EU’s tropical wood trade so far in 2018 is mainly due to a slight uptick in imports of plywood and charcoal.

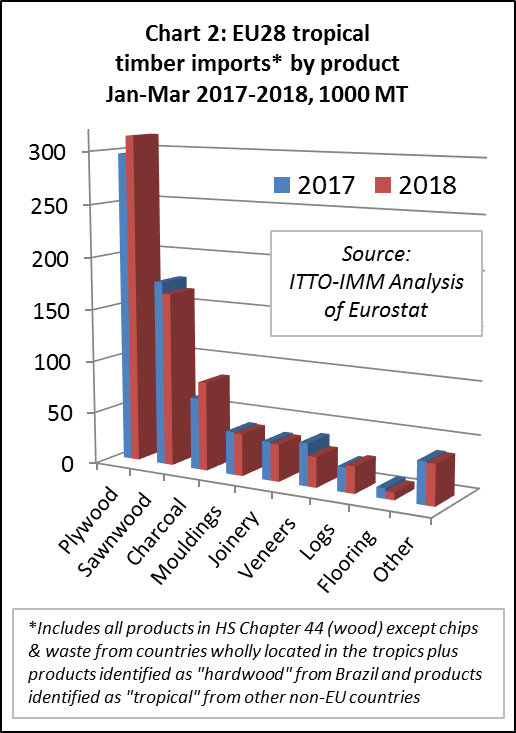

In the first quarter of 2018 compared to the same period in 2017, total EU imports of tropical wood products increased 1% to 740,000 MT. There was a 23% rise in imports of tropical charcoal to 85,000 MT, a 6% rise in imports of tropical plywood to 314,000 MT, and 9% rise in imports of other secondary products (such as fibreboard and sleepers) to 14,000 MT.

However, these gains were largely offset by a 6% decline in EU imports of tropical sawn to 166,000 MT, a 28% decline in imports of tropical veneer to 29,000 MT, a 2% fall in imports of tropical mouldings to 40,000 MT, and a 10% fall in imports of various tertiary products (such as flooring, glulam and other joinery, marquetry, and wooden tools) to 64,000 MT (Chart 2).

Recorded rise in UK tropical imports may be misleading

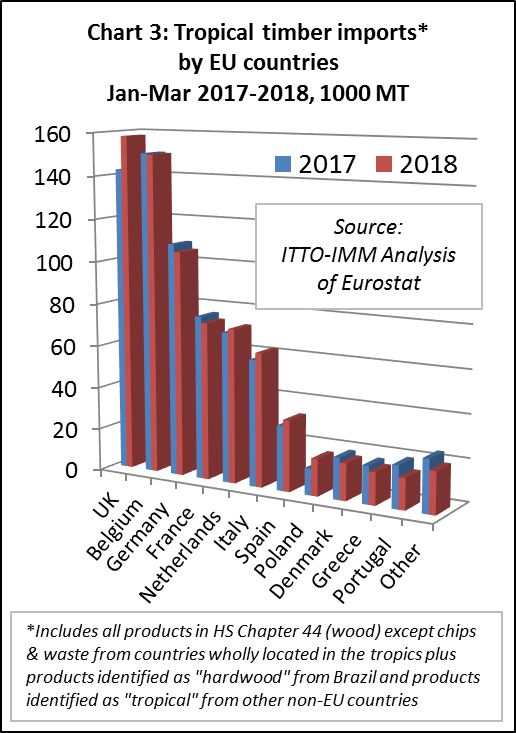

In the first quarter of 2018, imports of tropical wood products appear to have been more buoyant in the UK than other EU markets. UK imports were 158,000 MT during the period, 11% more than the previous year.

However, this gain was almost all due to an apparent rise in UK imports of hardwood plywood from Brazil. The sharp increase recorded in Eurostat import statistics is not matched by any significant increase in Brazilian export statistics for hardwood plywood to the UK. This may well be a statistical error (such as Elliottis pine plywood being misidentified as hardwood).

Other EU markets reporting growth in tropical wood imports the first quarter include the Netherlands (+3% to 72,300 MT), Italy (+6% 62,600 MT) and Spain (+10% to 33,300 MT). However, the fastest growth of all was in Poland which registered an increase of 39% to 17,300 MT. This was due almost entirely to a sharp rise in Poland’s imports of charcoal from Nigeria.

Imports of tropical wood products in Belgium were 150,000 MT in the first quarter of 2018, the same as in 2017. Imports in Germany and France slipped a little in the first three months of 2018, down 3% and 4% respectively compared to the same period last year. (Chart 3).

6% decline in EU imports of tropical sawn wood.

EU imports of tropical sawn wood decreased 6% to 166,100 MT in the first quarter of 2018. This was mainly due to a continuing slide in imports from Cameroon, on-going since the end of 2016. EU imports of tropical sawn wood from the central African country declined a further 24% to 49,000 MT in the first three months of 2017. Imports also fell from Congo (down 4% to 9,400 MT), and Côte d’Ivoire (down 21% to 6,800 MT)

However, after a decline in 2017, EU imports of tropical sawn wood from Malaysia increased 18% to 29,300 MT in the first quarter of 2018. There was also a rise in imports from Brazil (+3% to 27,600 MT), Gabon (+7% to 22,600 MT), and Ghana (+8% to 3,600 MT) and DRC _+36% to 3,000 MT). (Chart 4).

An 86% rise in EU imports of sawn wood from Indonesia (to 5,000 MT), a country which restricts exports in this product group to profiled wood, may be partly due to reclassification of some wood mouldings products from HS4409 to HS4407.

Introduction of the FLEGT licensing system in Indonesia since November 2016 has led to some changes in the HS codes used for Indonesian products by EU customs and operators to ensure consistency between codes identified on the licences issued in Indonesia and the codes entered on to customs forms for entry into the EU.

In the first quarter of 2018, tropical sawn hardwood imports declined 14% to 51,900 MT in Belgium, 9% to 18,600 MT in France, 30% to 10,700 tonnes in the UK, 11% to 6,800 MT in Germany, and 50% to 3,800 MT in Portugal. These losses were partially offset by a 33% rise to 35,200 MT in the Netherlands, a 22% rise to 17,800 MT in Italy and a 6% rise to 12,600 MT in Spain.

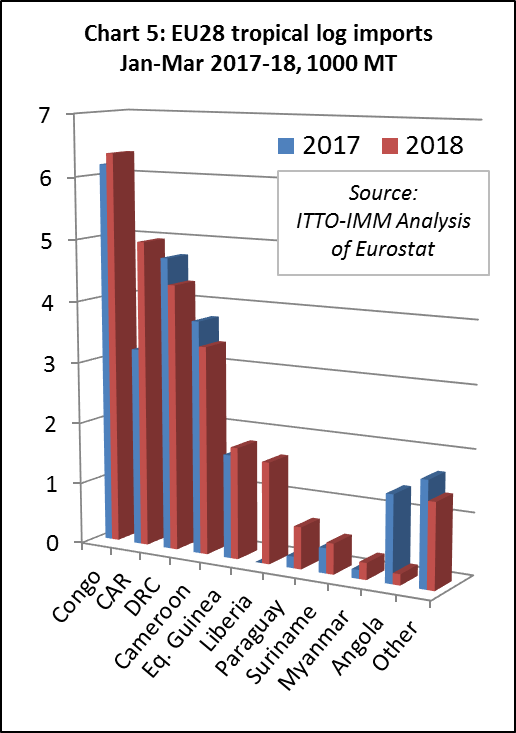

EU imports of tropical logs recover a little ground

After a downturn in 2017, EU imports of tropical logs recovered a little ground at the start of 2018. Imports of 25,500 MT during the first quarter of the year were 9% greater than the same period in 2017. EU imports of tropical logs increased from the two leading suppliers, Congo (rising 3% to 6,400 MT) and CAR (rising 54% to 5,000 MT).

EU log imports from Equatorial Guinea also increased during the period, by 8% to 1,800 MT. Imports from Liberia, of which there were none in the first quarter last year, were 1,600 MT in the same period this year.

However, during the first quarter of 2018, EU imports of tropical logs declined 9% from DRC to 4,300 MT and 11% from Cameroon to 3,400 MT. EU log imports from Angola, which increased sharply in 2017, were again at negligible levels in the first quarter of this year (Chart 5).

Most of the gain in EU imports of tropical logs in the first quarter of 2018 was concentrated in France (+43% to 11,400 MT) and Belgium (+15% to 5,800 MT). Imports of tropical logs in Portugal fell 32% to 3,800 MT during the period.

Stability in EU tropical decking imports

EU imports of tropical mouldings (which includes both interior mouldings and exterior decking products) fell slightly, by 2% to 40,200 MT in the first quarter of 2018. A 10% rise in imports from Brazil to 17,000 MT offset a 17% decline in imports from Indonesia to 14,900 MT. As noted earlier, the latter decline may be partly due to alterations in the HS codes used to record imports from Indonesia following introduction of FLEGT licensing.

EU imports of mouldings increased for some smaller suppliers of this commodity in the first quarter of 2018 including Malaysia (+29% to 2,800 MT), Peru (+33% to 2,000 MT) and Bolivia (+100% to 1,400 MT) (Chart 6).

In the first quarter of 2018, imports of tropical decking increased in France and Belgium but declined in Germany, the Netherlands and the UK.

Sharp fall in EU imports of tropical glulam

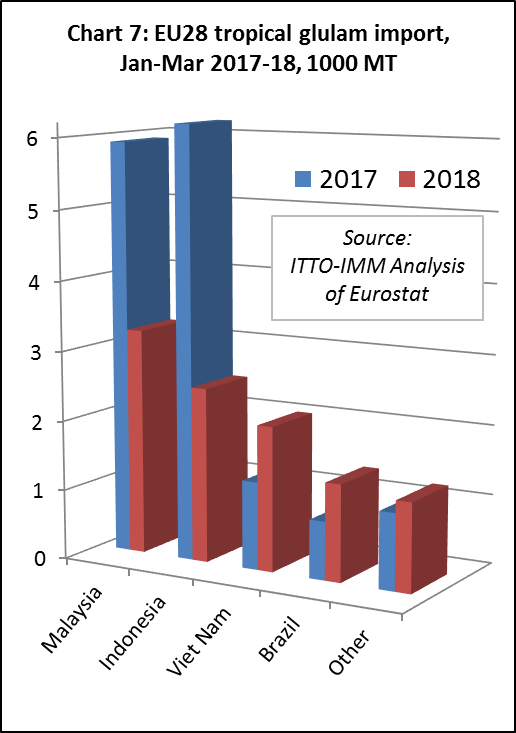

EU imports of tropical glulam, mainly laminated window scantlings, decreased 37% to 9,800 MT in the first quarter of 2018. Imports decreased from both the leading suppliers, falling 45% to 3,200 MT from Malaysia and 60% to 2,500 MT from Indonesia. (Chart 7).

Following introduction of FLEGT licensing in Indonesia, a proportion of Indonesian products previously identified as glulam (EU CN product code 44189010) is now being classified as plywood (EU CN Code 4412) on EU customs forms to ensure consistency with the FLEGT licenses issued in Indonesia. Indonesia has no code comparable to the EU code for “glulam” in their national system to classify products in trade.

In the first quarter of 2018 EU imports of tropical glulam fell by 73% to 1,880 in the Netherlands, by 18% to 3,000 MT in Belgium, and by 38% to 1850 MT in Germany. However, imports increased by 146% to 2,250 MT in France.

Note that EU import data for the first quarter of 2018 for tropical veneer, plywood, flooring, and wood furniture will be included in the next market report.

European economic recovery loses momentum

During the first quarter of 2018, there was a loss of momentum in the economic recovery that has been underway in the EU since the start of 2017. The pace of economic expansion in Germany was cut in half during the period due mainly to weaker trade.

The 0.3% increase in GDP in Europe’s largest economy was softer than forecast and the weakest in more than a year. Dutch and Portuguese growth also cooled more than expected in the first quarter, while a similar trend was seen across central and eastern Europe.

Overall, euro-area growth was only 0.4% during the 3-month period, well below expectations. It is unclear at this stage whether the slowing rate of growth at the start of 2018 is merely a soft patch or indicative of something more alarming.

So far, official forecasters have largely dismissed the sluggish start to the year — blaming factors such as colder weather — and expressed confidence that weakness will dissipate.

The IMF’s latest forecasts, published following the first quarter results, suggest that growth in advanced European economies, mainly the euro zone, would slow to 2.3% this year from 2.4% in 2017 and then decelerate to 2.0 percent in 2019.

The European Commission also downplayed concerns and has maintained its forecast that full-year growth will almost match the decade-high pace hit in 2017.

However, there are threats. The euro fell to six-month low after the German GDP figures and other discouraging data from the latest IHS Markit purchasing managers’ surveys which showed that forward looking indicators had also deteriorated, suggesting no immediate bounce-back.

The IMF latest report highlights that European governments have so far largely failed to use the breathing space offered by improved economic conditions to push forward with reforms needed to boost long-term growth.

Despite the recent growth, some of the biggest euro zone economies like France, Italy or Spain have been slow to further reduce their budget deficits towards a balanced position while others, like Belgium, are increasing the shortfall.

Concerns are also mounting in Europe about rising trade protectionism, higher oil prices, the fallout from Brexit scheduled for March next year, and the political situation in Italy.

Of these issues, the last is potentially the most critical. Economists calculate the cost of the promises made by Italy’s newly installed government – which include lower taxes, higher benefits, and earlier retirement – could reach Euro170bn, or about 10% of Italy’s GDP. This would add to the country’s Euro2.1trn debt mountain and potentially trigger the EU’s worst-case scenario: a Greek-style debt crisis in the eurozone’s third-biggest economy.

There are also clouds on the horizon in the UK. One of the UK’s leading economic thinktanks has slashed its forecasts for 2018 following evidence that growth almost came to a halt in the first three months of the year.

The National Institute for Economic and Social Research (NIESR) said it expected GDP expansion of 1.4% in 2018 – a sharp reduction from the 1.9% it had been predicting three months ago. The revision followed publication of official figures showing the UK economy grew by only 0.1% in the first three months of 2018 – well below the 0.5% the thinktank had been forecasting.

As elsewhere in the EU, it is not clear if this is just a soft patch or the start of a prolonged period of weakness. At present, NIESR still expects UK to pick up to average around 0.4% in each of the next three quarters.

The latest data on UK construction provides some little reassurance. A pick-up in housebuilding helped the building sector, which suffered from very poor levels of activity in the first quarter, to bounce back in April.

However, overall demand for new buildings in the UK remained subdued, according to the Markit/Cips UK construction purchasing managers’ index, with total new work rising only modestly on the month. While housebuilding bolstered growth in April, the picture was less positive in other areas of construction, with commercial building and civil engineering work rising only marginally.

UK construction market analysts suggest that heightened economic uncertainty, alongside lack of clarity on the Brexit negotiations, is creating a risk-averse mood among clients, leading to spending plans being delayed. Growth in the UK construction sector is also likely to be dampened by a planned 5.4% reduction in public sector investment this year.

PDF of this article:

Copyright ITTO 2020 – All rights reserved