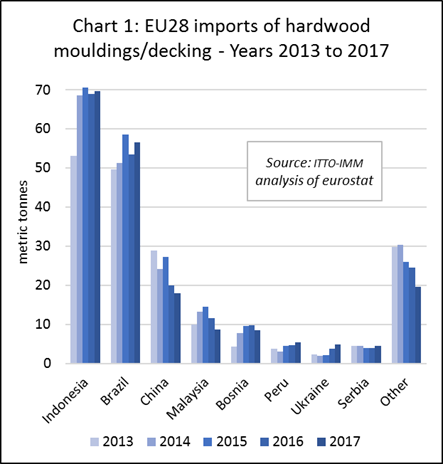

EU imports of “continuously shaped” wood (HS code 4409) includes both decking products and interior decorative products like moulded skirting and beading. Total EU imports of hardwood products under this heading declined by just over 3% in 2017, to 122,800 metric tonnes (MT). However, imports from Indonesia and Brazil, the two largest suppliers, increased last year.

Indonesia’s leading role as a supplier of this commodity group to the EU is due both to the popularity of bangkirai for decking applications in Europe, and to Indonesia’s ban on rough sawn exports encouraging greater focus on profiled products. After a steep rise in 2014, imports from Indonesia remained broadly flat in the next three years and were 69,600 MT in 2017, 1% more than the previous year (Chart 1).

Brazil has access to several Amazonian species like ipe, garapa and massaranduba that perform well as decking timbers. Following a 9% decline in 2016, EU imports from Brazil rebounded 6% to 56,600 MT in 2017.

China’s trade in this commodity with the EU has been declining in recent years owing both to rising costs of production in China and declining availability of raw material. Imports from China fell a further 10% to 18,000 MT in 2017. China depends on imported tropical timber with a strong preference for teak in the decking sector. China also supplies small quantities of interior hardwood mouldings to the EU market.

While total EU trade in decking and similar garden products has been gradually increasing in recent years due to a slow improvement in EU construction activity, tropical timber faces intense competition from substitute materials in this sector, notably Wood Plastic Composites (WPC), thermally and chemically modified European hardwoods and softwoods, and preservative-treated softwoods. Tropical hardwood decorative mouldings for interior use are also being replaced by European timbers and MDF.

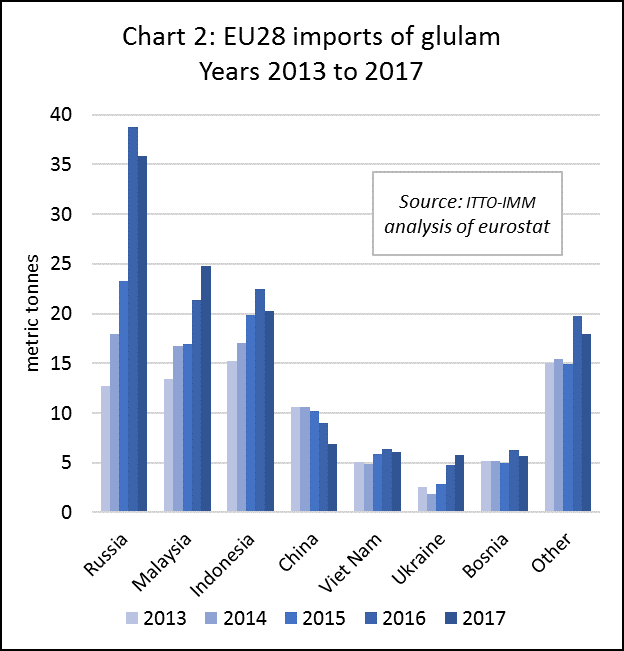

EU market for glulam challenging for external suppliers

Anecdotal reports indicate that the glulam sector in Europe struggled with over-supply and low margins in the 2013 to 2016 period. Taken together these trends suggest relatively poor prospects for external suppliers to expand glulam sales in the EU market.

Nevertheless, EU imports of glulam were increasing between 2013 and 2016 when they reached a peak of 128,700 MT. Last year total imports fell back 4% to 123,300 MT, but Malaysia, the leading tropical supplier, continued to make gains. Imports from Malaysia increased 16% to 24,800 MT in 2017 (Chart 2).

In contrast to Malaysia, in 2017 imports from Indonesia declined by nearly 10% to 20,300 MT and imports from Viet Nam fell nearly 4% 6,100 MT. Imports also fell 8% from Russia to 35,800 MT and 24% from China to 6,900 MT.

The relative strength of tropical glulam imports at a time of intense competition in the wider EU glulam market is partly due to the specific mix of products involved. Whereas much of the EU internal market comprises large beams and other structural elements, a large proportion of imports are more specialised small dimension products for non-structural applications.

Imports of tropical glulam have remained reasonably buoyant in response to improved demand in specific niche sectors, notably for durable laminated window scantlings in the Netherlands and Belgium.

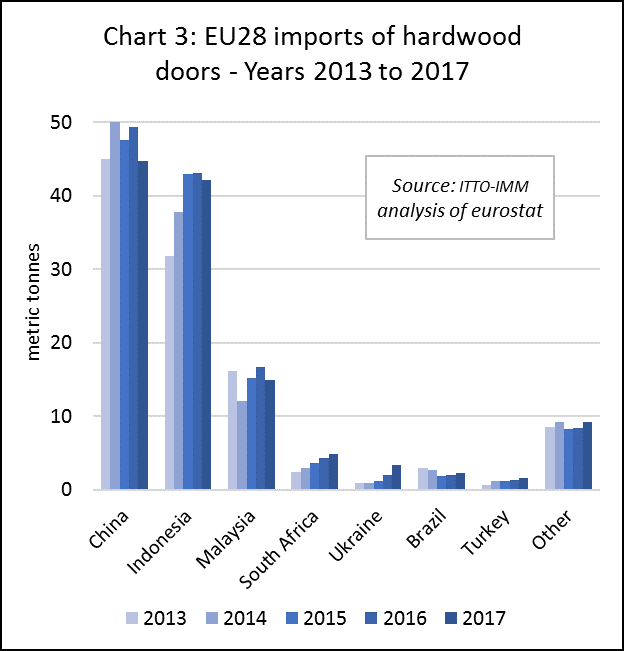

EU imports of wooden doors lose ground in 2017

Most new wood door installations in the EU comprise domestically manufactured products. Imports from outside the bloc account for less than 5% of total consumption value in the EU. Imports from the three largest non-EU countries – China, Indonesia and Malaysia – all lost ground in 2017. However, imports increased from several smaller external suppliers last year, including South Africa, Ukraine, Brazil and Turkey (Chart 3).

In 2017, EU imports of wood doors fell 9% to 44,700 MT from China, 2% to 42,100 MT from Indonesia, and 11% to 14,900 MT from Malaysia. In contrast, imports increased 11% to 4,800 MT from South Africa, 69% to 3,300 MT from Ukraine, 14% to 2,300 MT from Brazil, and 14% to 1,500 MT from Turkey.

The European wood door sector is increasingly dominated by products manufactured using veneered panels and finger-jointed timbers rather than from solid timber. Requirements to comply with higher energy efficiency standards and efforts to provide customers with long-life time guarantees are driving this concerted shift to engineered wood products.

Doors with a real wood veneer have also been losing share to doors manufactured using High Pressure Laminate (HPL) foils and white lacquered products. This is partly due to a shift in overall door production from Southern European countries such as Spain and Italy, which strongly favoured real wood veneer, to Germany where there is a very sophisticated foil and laminates industry.

German slowdown dampens European wood flooring demand

An insight into the current status of the EU wood flooring market and the wider economic situation in individual EU countries is provided by the report of the meeting on 4 April 2018 of the Board of Directors of the European Federation of the Parquet Industry (FEP).

According to the report, compared to the same period last year, provisional results for the first quarter of 2018 point to a continuation of the moderately positive European parquet consumption trends observed in 2017 with the exception of Germany which is reporting a significant decrease.

The report notes that new build projects are the main driver of the market for wood flooring in Europe, although renovation is creates significant additional activity.

It also notes that despite the long and wet winter in Europe, the availability of raw material is not a critical issue for the time being. This implies some easing of the supply problems that have emerged in recent years owing to the sectors very heavy reliance on oak which now accounts for around 80% of production.

The report includes a rapid-fire appraisal of the market situation in each of the countries represented by the FEP membership:

- Austria: parquet sales continued to increase by 2% in the first quarter 2018 compared to the same period last year.

- Belgium: parquet sales are estimated to have 3% during the first three months of 2018.

- Baltic States: Baltic countries’ markets showed a slightly positive trend in the first quarter 2018.

- Denmark: The Danish parquet market remains flat overall, a decrease in the retail market is compensated by rising demand from building contracts and projects.

- Finland: parquet sales increased by 1% in the first quarter, mainly driven by moderate growth in large projects while the residential market is stable.

- France: parquet sales are gradually recovering, rising an estimated 2% in the first quarter of 2018.

- Germany: parquet sales are estimated to have fallen 5% in the first quarter of 2018 compared to the same period in 2017. This decrease reflects the subdued residential market, a lack of installation professionals, intense competition from “wood look” floor coverings, and diminishing store space allocated for hardwood flooring by DIY retailers.

- Italy: parquet sales increased 2% in the first quarter of 2018 and continue to benefit from more positive economic developments in the country.

- Netherlands: parquet sales increased by an estimated 3% during the first quarter 2018 in line with improving economic conditions in the country.

- Norway: the market was flat with some signs of slight improvement (less than 1% growth) during the first months of 2018.

- Spain: despite the turbulent political situation, the Spanish market expanded slowly by between 1% and 2% in the first quarter of 2018.

- Sweden: parquet consumption increased 2% in the first quarter. Declining retail sales were offset by increased demand from building projects. Sweden is currently the most dynamic market in Scandinavia.

- Switzerland: parquet consumption remains flat but at a high level with numerous large on-going renovation projects.

Weak start to the year in UK construction sector

As a country without a significant domestic flooring manufacturing sector, the UK is the only large EU consuming country not covered in the FEP’s rapid appraisal of market conditions. However, information from the UK Construction Products Association (CPA) indicates market conditions for flooring and other joinery products in the UK deteriorated in the opening months of 2018.

According to the CPA’s market statement for the first quarter of 2018, the start of the year was a bad one for UK construction. Carillion, the UK’s second biggest contractor, went into liquidation in January and this led to an hiatus on infrastructure and commercial projects. Poor weather also badly affected work on site in February and March and, as a result, 2018 Q1 construction was around £1.5 billion lower than in 2017 Q4.

The CTA statement goes on to note that construction activity in the UK is forecast to be flat this year and rise by 2.7% next year, primarily driven by infrastructure and private house building.

Infrastructure output is forecast to grow 6.4% this year and 13.1% in 2019 as main civil engineering work commences on several large projects. In private housing, output is forecast to rise 5.0%, with demand for new build underpinned by government support for first home buyers.

This performance contrasts with other sectors of the construction industry, however. The sharpest decline is forecast in the commercial sector, where a post-EU Referendum fall in contract awards for new offices space since the second half of 2016 is expected to translate into a fall in activity this year. Office construction is expected to decline 20.0% in 2018 and 10.0% in 2019.

Market role of EUTR and FLEGT licensing

A key question for the long-term future of the EU trade in tropical timber products is the impact of the EU Timber Regulation (EUTR). This is particularly true of suppliers in those tropical countries, like Indonesia, that have a Voluntary Partnership Agreement (VPA) with the EU and are seeking an assurance that FLEGT licensed timber will benefit in the market from the “green lane” offered by EUTR.

FLEGT licensed and CITES certificated timber products are the only products recognised by EUTR as requiring no further checks by EU importers to ensure their legal status.

For those suppliers of tropical timber products that are not FLEGT licensed, there are key issues surrounding the types of information that the EU importers will accept as assurance that there is a negligible risk of illegal harvest.

These issues have been highlighted in recent weeks by the prosecution of one UK importer for a failure to comply with EUTR in relation to sawnwood imported from Cameroon. The prosecution was solely focused on the company’s due diligence systems relating to its purchases of FSC-certified ayous from Cameroon in January 2017.

Although the prosecution acknowledged that none of the material imported was from an illegal source, the company was found guilty of failing to adequately check the legality of the timber when placing it on the market.

The company was fined £4000 in the second successful EUTR prosecution in the UK. The first was last year when a designer furniture retailer was fined £5000 for importing a sideboard from India without carrying out the required due diligence assessment.

Commenting on the latest prosecution, a representative of the British Woodworking Federation said:

“Companies bringing timber products in directly from outside the EU need to have their own due diligence system in place even for one-off transactions and cannot rely on suppliers to carry this out on their behalf.

“This must include information about the supply of timber products, an evaluation of the risk of placing illegally harvested timber and timber products on the market and necessary steps to mitigate this risk; for example additional information and third party verification.

“Simply bringing in FSC, PEFC or similar Chain of Custody certified timber is not enough to satisfy the due diligence requirements for these importers, although FLEGT licenced timber would suffice.”

In practice, given the extra due diligence steps required to import even FSC certified timber into the EU market, EUTR should offer significant market advantages to tropical suppliers of FLEGT licensed timber.

At present that applies only to Indonesia, which has licensed timber for the EU market since November 2016. The latest data from the FLEGT Independent Market Monitor, hosted by ITTO, suggests that this market advantage may be filtering through into a rise in EU trade with Indonesia for product groups like plywood and decking that have been an immediate focus of EUTR enforcement activity.

There has been quite a sharp increase in EU imports of Indonesian plywood since November 2016, lending support to anecdotal reports of EU plywood importers being encouraged to stock more Indonesian product due to licensing. EU imports of decking products from Indonesia were sliding in the first half of 2017 but recovered in the second half of the year.

However, it would be a mistake to attempt to attribute these trends to a single cause, even one so significant as a regulation applicable to every company placing timber on the market in the EU. An increase in trade can be expected in a year when the EU economy began to grow more strongly after a long period of slow growth following the European debt crises.

It’s also apparent that the rise in trade with Indonesia during 2017 was not universal across product groups. EU imports of wood furniture from Indonesia were flat during the year, while imports of Indonesian flooring and glulam declined (for more details see http://www.flegtimm.eu/index.php/newsletter/flegt-market-news/54-eu-imports-from-indonesia-in-2017).

These trends seem to be confirming earlier forecasts in the ITTO MIS (16-30 Sept 2016 & 16-30 April 2017) that the combination of EUTR and FLEGT licensing offer an immediate opportunity for Indonesian suppliers to retake share in those sectors – like decking and plywood – where Indonesian products are familiar to EU importers and already favoured for their strong technical performance, but where demand has been dampened by concerns over the legality of wood supply.

However, in isolation, FLEGT licensing is less likely to generate immediate benefits in those high value sectors like furniture and joinery where the specific technical and environmental features of Indonesian wood products have been less significant barriers to competitiveness than wider issues such as labour costs, red tape, logistics, processing efficiency, innovation, and marketing.

In these sectors, increasing share may well be achieved if FLEGT licensing is combined with market development initiatives to improve the international competitiveness of Indonesian wood manufacturers across a wider range of issues, although this is likely to take time.

ClientEarth: EUTR not “effective, proportionate and dissuasive”

The potential value of FLEGT licensing is also partly dependent on the extent to which EUTR is being implemented consistently across the EU. This is a question considered in a new report issued by ClientEarth, a UK based NGO specialising in analysis of environmental law.

In the report, ClientEarth provide their assessment of whether the enforcement regimes, which under EUTR are required to be implemented by the individual EU member countries, are “effective, proportionate and dissuasive” according to the law.

The report highlights that although the EUTR was first introduced in March 2013, some EU member countries delayed introduction of a national enforcement regime for some time after that date, although nearly had done so by the end of 2016.

ClientEarth show that penalties for EUTR infringements vary widely across the EU. Certain Member States (such as Austria, Poland, Romania and Bulgaria) have chosen a penalty regime relying mainly on administrative penalties; others (such as Denmark and the Netherlands) rely mainly on criminal penalties for key EUTR obligations. Some Member States (such as Belgium, Finland, France, Germany and Italy) have adopted a combination of the two systems.

EUTR penalties include notices of remedial actions, seizure of timber, suspensions of authorisations to trade, fines and imprisonment. ClientEarth conclude that competent authorities and Member State courts have been more actively enforcing the EUTR since 2016 compared to the years 2013 to 2015 when almost no penalties had been imposed.

ClientEarth summarise all the EUTR actions that have been reported publicly to date referencing the two UK cases mentioned earlier together with two cases in the Netherlands, two cases in Sweden, and one in Germany.

In the Netherlands, a fine of €1,800 per cubic metre of timber was imposed on a company for a failure to gather information tracing back the entire supply chain of imported sawn timber deemed to be risky from Cameroon. In another case, a preventive measure was ordered against two Dutch importers of Burmese teak, imposing a fine of €20,000 per cubic metre for each teak shipment placed on the market in breach of the EUTR.

In Sweden, the cases so far have all involved prosecutions for a failure to undertake appropriate due diligence in imports of Myanmar teak. One company was fined SEK 17,000 (approximately €1,700), another the much larger amount of SEK 800,000 (approximately €79,500) due to a failure to implement measures stipulated in an earlier injunction. In addition to these cases which led to fines, in 2017 several other Swedish companies were prohibited under EUTR from importing any products containing Burmese teak.

In Germany, an administrative court confirmed in 2017 a decision by the competent authority taken in 2013 to confiscate timber imported from the DR Congo due to irregular documentation. The timber will be auctioned and the money from the auction allocated to the federal budget.

While these few cases have been brought in a limited number of Member States, according to ClientEarth, ‘soft’ approaches involving no punitive action and a mainly educative purpose still seem to be the preferred enforcement option in many Member States. Such measures include advice letters and warnings, as well as injunctions and notices of remedial action without non-compliance penalties.

Based on this analysis of the cases brought date, the text of laws introduced at national level, publicly available information on regulatory checks and sanctions regimes, and interviews with several competent authorities, ClientEarth conclude that “EUTR penalties rarely seem enforced to the ‘effective, proportionate and dissuasive’ legal standard, even in Member States where a positive trend in EUTR enforcement is noticeable.”

Comment on ClientEarth assessment of EUTR

The ClientEarth study has limitations. The conclusions are based on a technical analysis of sanctions regimes – considering, for example, whether the costs of sanctions are likely to significantly exceed the costs of implementing EUTR due diligence measures and therefore to provide an effective deterrent.

There is no actual appraisal of whether the national differences in sanctions regimes is leading to significant failures in enforcement or other negative impacts, such as diversion of illicit trade through countries with weaker enforcement regimes.

It is notable that in none of the cases cited was it ever proved that the wood was from an illegal source – there is no obligation under EUTR on the EU authorities to provide such proof – the prosecutions were all due to the failure on the part of the importer to demonstrate compliance to the due diligence steps required in EUTR.

The fact that these prosecutions were brought and led to significant sanctions, even without evidence of illegality at source, suggests that the law has teeth and places a significant lever to encourage more far-reaching due diligence measures in the hands of the EU authorities.

It’s the kind of regulatory power that needs to be used wisely to avoid unintended consequences, such as the creation of technical barriers to trade, feeding of protectionist instincts and discrimination against smaller operators.

ClientEarth acknowledge that their conclusions are based on inadequate information, noting that there is relatively little publicly available information about the number of penalties that have been applied since the EUTR has been in force. The EC has already indicated an intent to improve transparency on this issue and much more information is expected to be available later in the year.

ClientEarth is also critical of what it refers to as ‘soft’ approaches, arguing that they do not provide an effective deterrent to timber products from placing timber at risk of being illegal on the EU market.

This is one interpretation, but in practice EUTR is a complex and innovative law for which most national authorities have had to acquire new knowledge and skills, often from the private operators they are required to regulate, many of which were implementing responsible procurement policies for years even before EUTR was introduced.

Regulating the purchasing decisions throughout 28 Member States of a fragmented industry with nearly half a million enterprises, one in five of all manufacturing enterprises in the region, is unprecedented.

In the early years of implementing EUTR, there has been some confusion and ambiguity over the exact measures required by individual operators to demonstrate conformance. Communicating to timber operators, often small traders with only limited access to legal advice, that they cannot accept either FSC certificates or government documents at face value as evidence of a “non-negligible risk of illegal harvest” takes time and effort.

It is challenging to explain to operators that it is their responsibility to identify which products are “non-negligible risk”, particularly when the EC and other regulators cannot advise on the relative risks associated with different supply countries and product groups.

In such a situation it would be unjust to rush to prosecution – and runs the risk of discrediting the legislation, particularly amongst those operators being regulated. The success of the EUTR to date has been built to a significant extent on the active support of the private sector within the EU. This support would quickly evaporate if a perception arose that it was just being used as a rod to beat the industry.

A lengthy period of “soft” regulation seems most appropriate, at least until such time as guidelines and supporting information sources have been properly developed and communicated and the authorities are sufficiently competent to accurately interpret and enforce the law.

However, there may be a distinction between certain member states using “soft” measures as part of a concerted effort to evolve an effective, efficient and equitable regulatory program, and others that may be hiding behind these measures to avoid more meaningful, and potentially costly, action.

If the latter attitude is widespread it could have the negative consequences mentioned by ClientEarth; an unequal playing field for trade in the EU, undermining the efforts of those operators that are conscientiously implementing due diligence procedures, undermining demand for FLEGT licensed timber, and encouraging diversion of illicit trade through less regulated countries.

So far, the information gathered by ClientEarth is not sufficient to judge the effectiveness of EUTR and their conclusion that the law does not provide a reliable deterrent to trading illegally harvested wood seems premature.

A clearer picture will emerge only when the EU publishes more comprehensive information on the regulatory measures and sanctions introduced at national level in the EU and with more detailed analysis of actual trade flow trends and the compliance steps being taken by operators across the EU.

PDF of this article:

Copyright ITTO 2020 – All rights reserved