Over the last 5 years, the words “flat”, “stagnant” and “slow” have frequently been used in relation to the European wood market. At the start of 2016, the situation has hardly changed. Overall growth in the European construction sector and wider economy has picked up only slowly since hitting bottom in early 2013. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that GDP in the 28 European Union countries will grow 2% in 2016, marginally up from 1.9% in 2015. But there is mounting concern that the world economy will enter a cyclical downturn before Europe regains the ground it lost in the financial and euro crises.

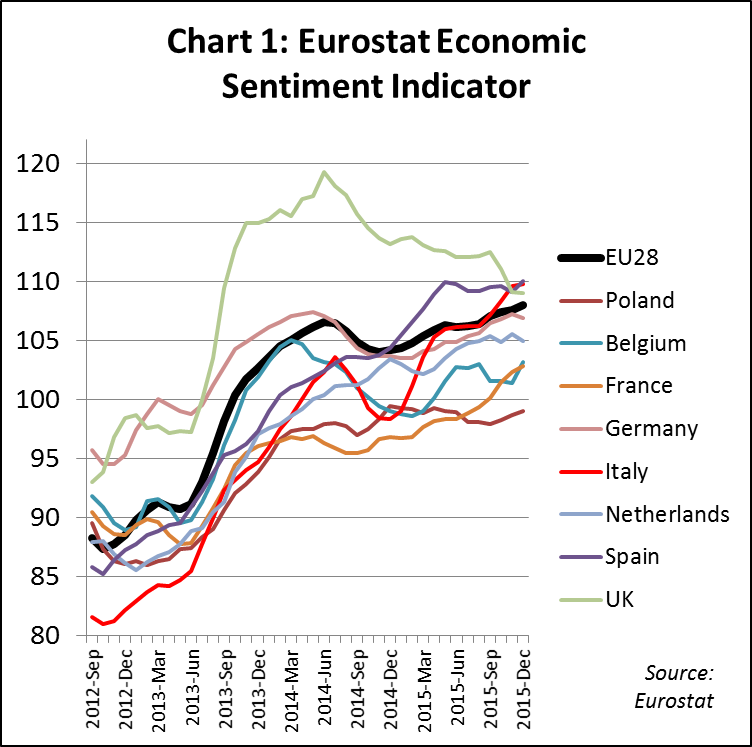

Overall there’s been some convergence in economic performance between EU Member States since mid-2015. This convergence is particularly apparent from the Eurostat Economic Sentiment Indicator (Chart 1) based on a monthly survey of perceptions and expectations in five surveyed sectors (industry, services, retail trade, construction and consumers) in all EU Member States. Although still positive, over the last six months economic sentiment has declined in the UK, the one large EU economy that recovered relatively early from the financial crises. Meanwhile sentiment has improved sharply in several countries that were lagging, notably Italy, Spain and France.

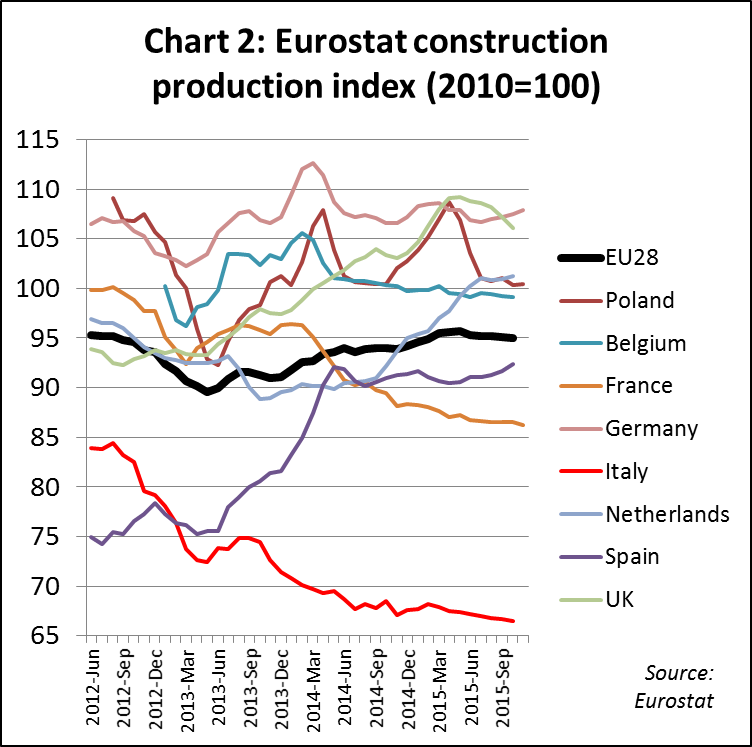

The Eurostat Construction Production Index (Chart 2) shows that the recovery in EU construction effectively stalled after March 2015, with activity stuck at only around 95% of the level in 2010. Construction activity in France and Italy was at historically low levels in 2015 and continued to decline throughout the year. Activity also lost ground in the UK and Poland, countries which were driving recovery in 2014 and early 2015. More encouragingly, activity remained robust in Germany, was rising in the Netherlands and at least remained stable at a higher level in Spain.

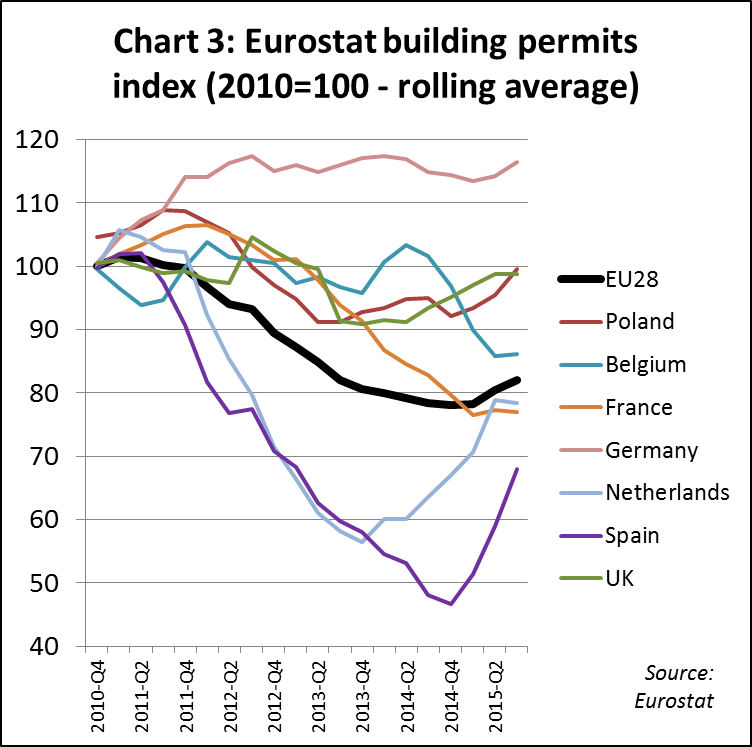

Slight uptick in building permits

The Eurostat Building Permits index (Chart 3), a forward-looking indicator, also provides some encouragement that the workload of the European construction industry will improve in the near future. There was an uptick in the level of building permits issued across the continent in the second half of 2015. This was particularly driven by a significant increase in building permits issued in Spain and the Netherlands. There was also a rise in building permits issued in the UK and Poland suggesting construction sector growth in those two countries will resume in 2016. Building permits remain at a high level in Germany.

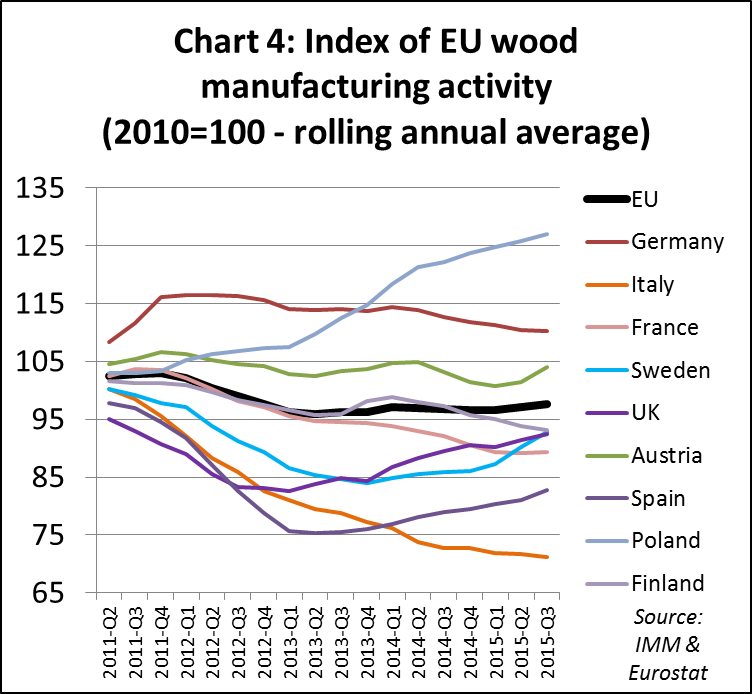

Demand for wood products has benefitted only a little from Europe’s slow economic recovery in the last three years. This is evident from the Eurostat index of EU wood manufacturing activity which covers the sawmilling, veneer, panels and joinery sectors but excludes wood furniture (Chart 4). European wood manufacturing activity remained stalled at around 97% of the 2010 level between the start of 2014 and second quarter of 2015. However there was an encouraging uptick in the third quarter of 2015, with activity increasing in Poland, Austria, UK, Sweden, and Spain. Rising activity in these countries during this period was sufficient to offset a slowdown in Germany and Italy, respectively the first second largest wood manufacturing countries in Europe.

Wood yet to make significant inroads into market share of other materials

The stasis in European wood manufacturing activity is a reflection of the slow growth in the European construction sector. It also suggests that wood has yet to make significant inroads into market share of alternative materials. Competition between suppliers of different wood products – such as between panels and sawn wood and between temperate and tropical hardwood – also remains intense.

While total European demand for wood products has remained flat, there are on-going significant shifts in the source of demand. Markets for sawn wood and wood-based panels have been particularly hard hit by the economic downturn and stagnation of the building and furniture sectors. The wood veneer sector has suffered profoundly from the contraction of the southern European joinery manufacturing industry and has come under intense pressure from substitute materials and new finishing techniques across the European continent.

However new opportunities are arising for value-added engineered and other forms of modified wood products, particularly in structural applications. The combination of strong technical performance and reduced overall costs of construction are the main drivers for uptake of these modern wood products. The carbon and sustainability message is a welcome bonus for those specifiers and contractors keen to burnish their green credentials. The relatively positive outcome of the recent Climate Change conference in Paris (see below) gives some confidence that this latter issue may become a more prominent driver in the future.

Euroconstruct forecast 3% growth in construction in 2016

At their 80th conference in Budapest in December, the independent research organisation Euroconstruct projected that total construction output in Europe increased 1.6% during 2015. This compares to their more optimistic forecast of 1.9% growth made at the previous Euroconstruct Conference in June 2015. However Euroconstruct is now more optimistic about prospects for 2016, forecasting 3% growth during the year (compared to their June forecast of only 2.4% growth). Euroconstruct also forecast growth of 2.7% in 2017 and 2% in 2018.

Euroconstruct estimate European construction output will have a value of €1412 billion in 2016, €1450 billion in 2017 and €1478 billion in 2018. This compares to a peak of €1532 billion just before the financial crises.

Euroconstruct forecast that the construction sectors of all 19 countries represented by the organisation will grow between 2016 and 2018. They note that during 2015, growth was particularly rapid in Ireland (+10.6%), Slovakia (+10.3%), Czech Republic (+7.4%), and the Netherlands (+6%).

In 2016-2018, annual construction growth is expected to exceed 7% in Poland and Ireland. However, the five largest construction markets in Europe – Germany, UK, France, Italy, and Spain – are also expected to grow more strongly and together will contribute more than two thirds of the forecast market expansion in 2016.

In recent years, much of the growth in European construction activity has been in repair, renovation and maintenance. These activities were responsible for 60% of the total residential market in 2015. However, Euroconstruct suggest that much increased growth in construction activity in 2016-2018 will be in the residential new build sector. This will be driven by the massive influx of migrants arriving in Western European countries such as Germany, the Netherlands, and to Nordic countries of Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. Using conservative assumptions, it has been calculated that in the next three years, excess demand for social housing will be at least 900,000 people, for whom the current social housing capacity is insufficient.

Euroconstruct suggest that the non-residential market will also grow in all 19 Euroconstruct countries during 2016 and that this growth will stall in only two countries – Finland and Sweden – in 2017.

Implications of Paris Agreement for forests

The UN climate summit in Paris that ended on December 12th did not deliver on all fronts, providing no guarantee that the world will avoid the worst impacts of climate change. However it did produce the most promising international climate agreement in years. Critically, the agreement built on initial commitments of over 180 countries to reduce their carbon emissions and includes a review clause to encourage countries to increase their pledges in the near future.

As the only the economic sector to be referenced explicitly, the Paris agreement also raised the political profile of forestry and signalled that cutting emissions from deforestation and promoting sustainable forestry is now recognised globally as one the most efficient ways to address climate change.

To make Paris a lasting success, it’s now important that the key agreements on issues such as financial support, the increase of emission-reduction pledges, and Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) are further developed and implemented in the months and years ahead.

The agreement is built on the commitment of signatories to deliver against “Intended Nationally Determined Contributions” (INDC) to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. By allowing countries to voluntarily declare their own commitments, discussions in Paris side-stepped the serious political conflict created in earlier negotiations which sought to allocate specific targets for emissions reductions to individual countries.

The downside of this approach is that, in aggregate, the commitments made fall well short of what the scientific community argues is needed to limit the global temperature rise to 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, the widely recognised threshold for major economic and environmental disruption.

The upside is that the agreement achieved unprecedented levels of political support. Close to 150 world leaders were in Paris to mark the start of the talks and negotiators from 195 countries signed off on the agreement when the talks ended. Paris was also significant for the high and positive levels of business engagement, a testament to the growing momentum behind global climate policy.

And while the INDC’s in aggregate fall short of what is required, some national commitments are ambitious and together they signal that measures to reduce carbon emissions will be an increasing factor in political and economic decision-making worldwide in the future.

For example the EU committed to reduce GHG emissions to 40% below 1990 levels by 2030. China indicated that it will reduce carbon intensity to 60-65% of 2005 level by 2030, increase the non-fossil fuel in national energy supply to 20%, and continue to expand forest area. The United States stated that it would reduce GHG emissions to 26-28% below 2005 level by 2025.

Many developing countries included action against deforestation in their INDCs. For example Brazil committed to “strengthening policies and measures with a view to achieve, in the Brazilian Amazonia, zero illegal deforestation by 2030 and compensating for greenhouse gas emissions from legal suppression of vegetation by 2030.”

Forestry related measures were also prominent in the text of the agreement. Article 5 encourages countries to “take action to implement and support, including through results-based payments” REDD+ activities. It also explicitly recognises “the role of conservation, sustainable management of forests and enhancement of forest carbon stocks in developing countries.”

The overarching “decision” that Annexes the Paris Agreement recognised “the importance of adequate and predictable” finance for REDD+ activities. Although the ‘rules of the game’ for REDD+ were already agreed – thus legitimising and ‘regulating’ REDD+ activities – the political signal of Article 5 is very important. It shows forest nations that this is a long-term game. This in turn should give added confidence to continue with REDD+ strategy and readiness activities.

Several groups of nations used the opportunity offered by the Paris Conference to launch new forestry-related initiatives. African nations, with support from NGOs and the German government, launched AFR100 at the Global Landscapes Forum during the Paris meeting. AFR100 is an initiative to restore 100 million hectares of degraded forest lands before 2030. It is led by ten African countries: the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Kenya, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Niger, Rwanda, Togo and Uganda.

There was also a “Leaders’ Statement on Forests and Climate Change” issued jointly by the governments of Australia, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, France, Gabon, Germany, Indonesia, Japan, Liberia, Mexico, Norway, Peru, United Kingdom and the United States. The Statement included a commitment to intensifying efforts to protect forests, to significantly restore degraded forest, peat and agricultural lands, and to promote low carbon rural development. It also included commitment to large-scale implementation of national REDD+ and sustainable land-use and climate change programs and, importantly, to generate and reward verified results.

Leaders from developing and developed countries also launched specific partnerships to help reduce deforestation. For instance, Brazil and Norway extended to 2020 their partnership to reduce deforestation in the Amazon Forest and Norway committed new financial support. Norway, Germany and the UK also pledged to provide US$5 billion from 2015 to 2020 for REDD+ programs.

Some private sector representatives of the private sector were also keen to lend their support. The co-chairs of the Consumer Goods Forum – M&S and Unilever – issued a statement that they will preferentially buy agri-commodities from areas that have “designed and are implementing jurisdictional forest and climate initiatives”.

Building on their commitment to “deforestation-free” sourcing policies through the New York Declaration on Forests, the two companies said in future they will preferentially source from jurisdictions that demonstrate commitment and progress towards an ambitious national INDC which includes a strategy for reducing emissions from forests and other lands whilst increasing agricultural productivity and improving livelihoods.

But perhaps more significant for forest policy than these statements of intent, was a pivotal reference in the Paris Agreement to the importance of “removals by sinks of greenhouse gas emissions in the second half of the century” to rapidly reduce global emissions after they peak “as soon as possible.” There was combined with a transparency clause which makes clear that removals by sinks must be included in national emissions inventories.

The implication is that forests – a vast sink which can be increased through active management – are acknowledged to be central to the solution of global climate change. Countries worldwide are also under an obligation to account accurately and regularly for all the carbon stored in the vegetation and soils in forests, as well as in agricultural land and protected areas and in the products of these lands (such as wood, crops, and biomass). As this data is collected and analysed, new market opportunities should arise for sustainable timber products as it becomes increasingly clear that increased use of such products is a particularly efficient way to reduce carbon emissions.

PDF of this article:

Copyright ITTO 2020 – All rights reserved