The French tropical wood company Rougier reported revenues of €78.5 million for the first-half of 2016, down 9.3% from the same period the previous year, in their consolidated accounts issued at the Board of Directors meeting in October. At the same meeting, the company also launched a strategic action plan to improve the group’s profitability and financial resources.

According to Rougier, the first half of 2016 was affected by a drop in sales prices for some of the timber species sold and weak demand on several markets in Asia, particularly China, and the Americas, as well as highly volatile levels of demand in the Middle East and North Africa. These developments have been partially offset by the dynamic performance for sales in Europe and certain sub-Saharan African countries.

Sales to Europe, accounting for 51.1% of group revenue, increased 6.8% in the first half of 2016, while sales to Sub-Saharan Africa, accounting for 11.3%, were up 19.5%. However, sales declined to all other regions including: Asia (down 25%, 26.7% of revenue); Middle East and North Africa (down 30.3%, 6.2% of revenue); and Americas and Pacific Region (down 37.6%, 4.5% of revenue).

The slowdown in demand in certain emerging countries has particularly impacted Rougier’s sawn timber sales. Some of the decline in sawn timber sales was offset by improving log sales in the second quarter of 2016 when there was an upturn in exports from Cameroon and strong local demand in Gabon driven by the resumption of sales of certain high value-added timber species, such as Kevazingo, which had been suspended by a government decree in the second half of 2015.

Performance of Rougier’s Import-Distribution branch in France has continued to improve with diversification of products offered and customers served. Rougier’s plywood and veneer sales achieved strong growth in the first half of 2016, supported by rising demand in Europe. However, in Gabon the turnaround in forest production and plywood was held back by insufficient levels of productivity in the sawmills. While Rougier’s operations in Cameroon and Congo have remained profitable, margins have been reduced as demand across the full range of products has declined with significant volatility in the main emerging markets.

Rougier expects sales to gradually improve over the second half of the year. The Group has carried out an in-depth strategic review of its activities and mapped out an action plan to restore profitability over the coming years. The action plan is based primarily around the strategic realignment of operations in Africa: focusing on higher value-added production activities, reorganizing industrial resources and starting up the first production operations in the Central African Republic from early 2017. Its deployment will be supported by a major cost reduction program in all the Group’s subsidiaries.

EIA alleges companies importing Myanmar teak are in breach EUTR

According to an article by Mongabay (www.mongabay.com), following a two-month undercover investigation, the campaigning NGO Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) allege that nine companies in five EU countries had failed to meet the EU Timber Regulation (EUTR) for legal importation of Burmese teak from Myanmar. EIA contends that all teak from Myanmar for sale in the EU should be considered illegally sourced.

As background, Mongabay observe that in 2012 the EU lifted a ban on timber imports from Myanmar while, in August this year, the Myanmar government imposed a moratorium on all logging until March 2017 to allow the country’s forests to recover. That means that all wood currently moving from Myanmar to international markets must come from existing stockpiles.

Mongabay report that EIA staff posed as prospective buyers and approached nine importers working in five EU countries and requested information on the source of the teak being imported. However, according to EIA, the companies consistently failed to identify the source.

The EUTR requires that companies doing business with countries where there is a non-negligible risk of illegal harvest take steps to mitigate any risk of sourcing illegal wood by identifying the original concession of harvest. According to EIA, businesses operating in the Netherlands, Italy, Belgium, Denmark and Germany have failed to meet this obligation.

According to Mongabay, EIA have acknowledged that the importers they met with appeared to be trying to follow the rules, but in this instance they were relying on information and documentation supplied by the Myanmar Timber Enterprise (MTE) at point of export and had stopped short of looking further upstream in the supply chain.

The importers involved have since argued that this type of upstream investigation in Myanmar just isn’t possible or appropriate as the MTE does not allow anybody to go back to the forest operator to verify documentation. They say the allegations are unfounded, and argue that they cannot be held accountable for problems in a supply chain controlled by the Myanmar government.

However, EIA allege that the MTE is exporting parcels of teak claimed to originate from a single location which actually comprise logs from multiple areas with fake origin documents. EIA claim that “in simple terms, no teak from Myanmar can legally be placed on the EU market due to the high risk of illegality associated with timber from that country and the lack of transparency by its Government to allow access to information that might demonstrate compliance.”

The importers argue that If there are inconsistencies in the certification process for the country’s timber, those issues should be sorted out at the government-to-government level, between the EU and Myanmar.

More at: https://news.mongabay.com/2016/10/illegal-myanmar-teak-importation-widespread-to-eu-investigation-finds/

Asian wood furniture manufacturers losing share in European market

There was a robust rebound in EU wood furniture production and trade in 2014 and 2015. As noted in earlier ITTO reports, wood furniture production value in the EU (excluding kitchen furniture) was €31.15 billion in 2015, 4.4% more than 2014 and nearly 9% up on 2013, with gains made in all the main EU manufacturing countries. EU imports of wood furniture from outside the EU were worth €5.73 billion in 2015, 13% more than the previous year and 25% up on 2013. EU exports of wood furniture rose to €8.73 billion in 2015, up 3.5% from 2014 and 6% more than in 2009.

While no EU furniture production data for 2016 has yet been published, early signs are that production has continued to rise this year even while external trade with non-EU countries has declined. In other words, European manufacturers are taking a larger share of the internal EU market in 2016, squeezing out overseas competitors at home as their efforts to expand sales to non-EU countries are beginning stall.

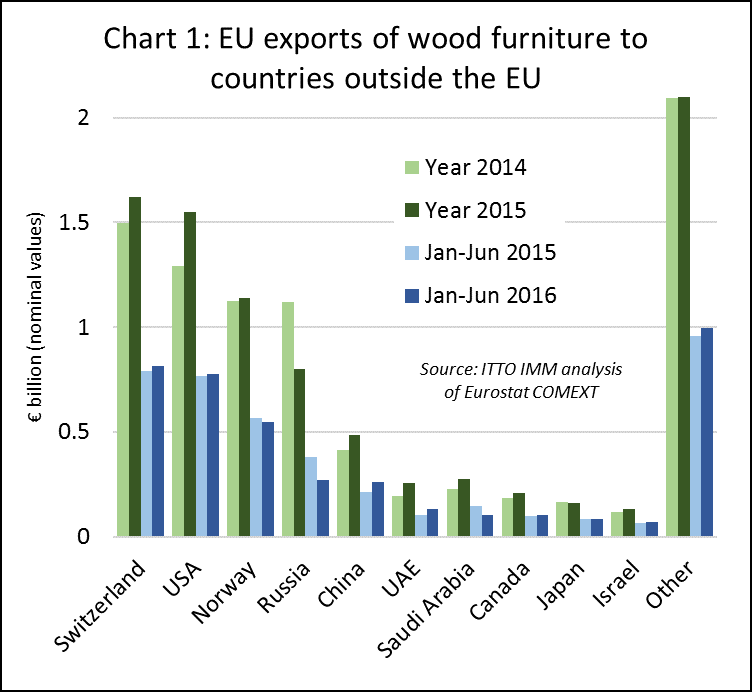

Eurostat data shows that the value of wood furniture exports by EU countries to other countries within the EU was €8.16 billion in the first half of 2016, 7.3% more than the same period in 2015. In contrast, the value of exports to countries outside the EU declined 1% to €4.16 billion in the first half of 2016. The slowdown in EU exports this year is mainly due to a 30% decline in exports to Russia. EU exports to other countries has continued to rise (Chart 1).

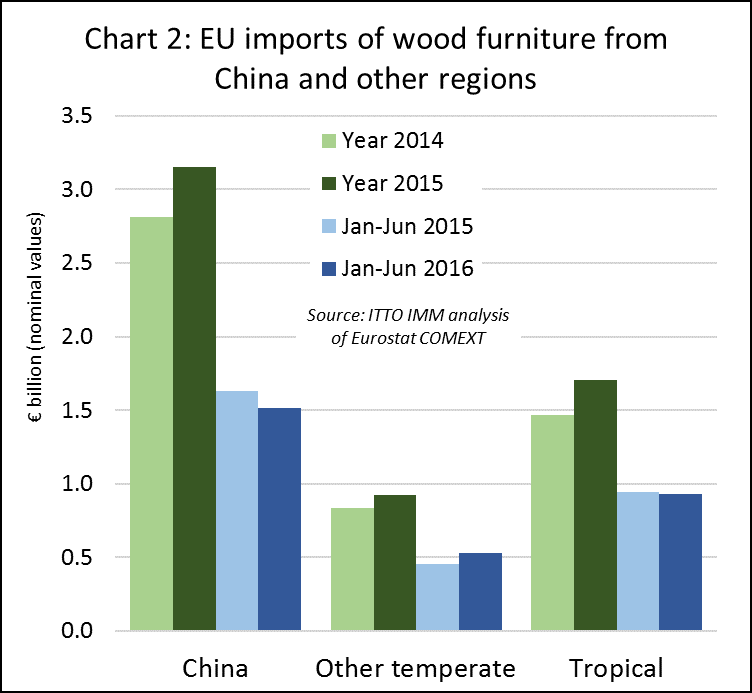

Meanwhile external suppliers of wood furniture, particularly in the tropics, seem to be struggling in what has become an extremely competitive market. The EU imported wood furniture with a total value of €2.97 billion in the first six months of 2016, 2% less than the same period in 2015.

After making significant gains in the EU market in 2015, EU wood furniture imports from China and tropical countries have slipped back this year. In the first six months of 2016, import value from China declined 7% to €1.51 billion and import value from tropical countries declined 1% to €930 million. However, EU import value from non-EU temperate countries increased by 16% to €528 million, with particularly large gains by Turkey, Bosnia and Serbia (Chart 2).

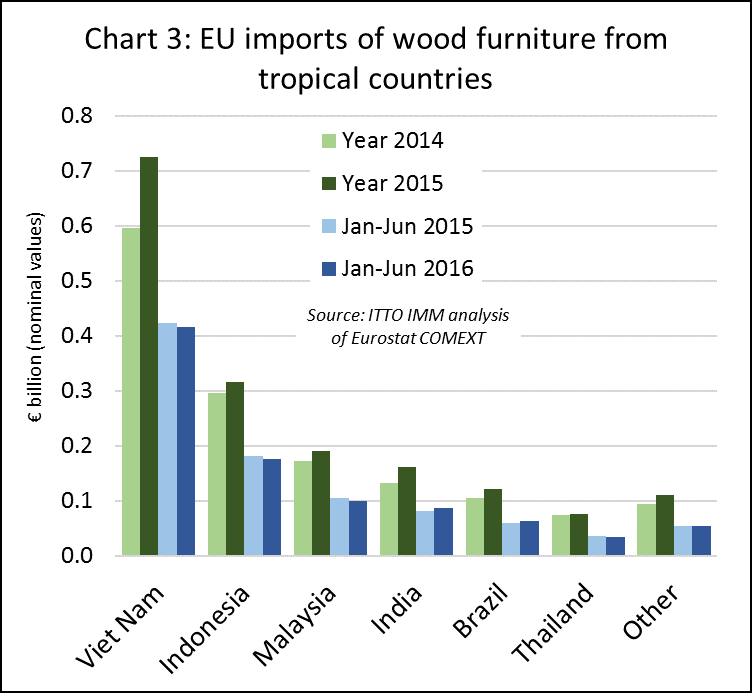

EU import value of wood furniture declined from all of the largest South East Asian suppliers in the first six months of 2016. EU import value declined by 1.5% from Vietnam to €416 million, by 3.1% from Indonesia to €176 million, by 5.2% from Malaysia to €100 million, and by 8.8% from Thailand to €34 million. However, there were gains in imports from India (+7% to €87 million) and Brazil (+7% to €63 million). (Chart 3).

Overall the signs are that, unlike in North America, domestic manufacturers are maintaining, even extending their domination of the European wood furniture market. There are many reasons for this. An obvious short term factor is weakening of European currencies in the last 2 years – particularly the UK pound since Brexit – against the dollar and Chinese yuan. More enduring factors include: the relative high degree of fragmentation in the European retailing sector – which greatly complicates market access for overseas suppliers; the underlying strength of European furniture manufacturers and their brands in terms of innovation and design; the obstacles to overseas suppliers complying with complex EU technical and environmental standards; and the expansion of furniture manufacturing in Eastern Europe, a location which combines ready access to raw materials, relatively cheap labour, and the internal EU market.

While it seems likely that domestic manufacturers will continue to dominate Europe’s wood furniture market in the years ahead, there are significant changes underway which are altering the terms of trade. While some changes are likely to create new obstacles for external suppliers, others may provide opportunities.

Two factors are particularly significant and explored in the following sections: the decision of the UK to leave the EU, so-called Brexit; and the strategy of IKEA, already a dominant force in the European market place, to increase their market share through a strategic focus on “sustainability” and all that implies for product design, material procurement, energy efficiency and waste management.

Brexit: far-reaching consequences for EU wood furniture market

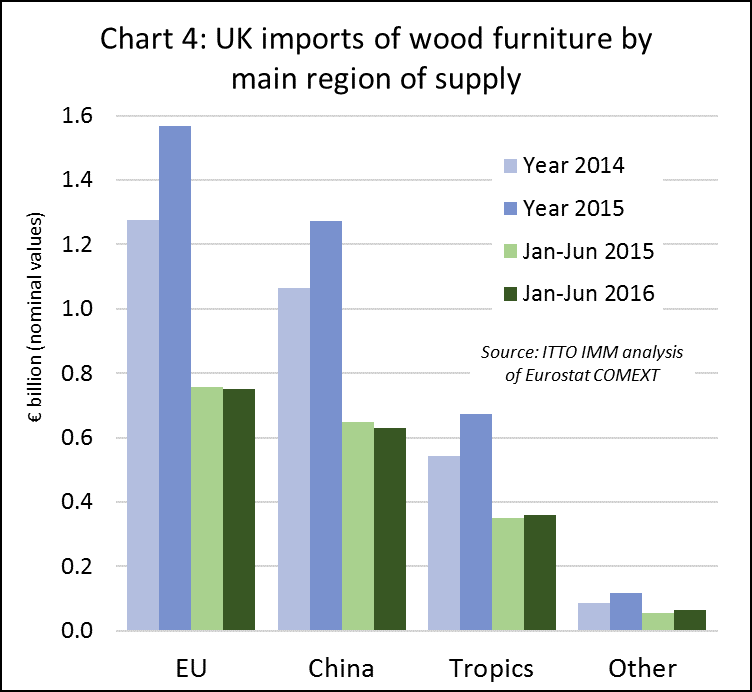

Brexit is particularly significant for the wood furniture sector as the UK is the largest single EU destination for this commodity imported from outside the EU. In 2015, the UK accounted for 36% of all EU imports of wood furniture from outside the single market. This is due to the relatively high degree of consolidation in the UK’s furniture retailing sector compared to other EU countries, and the UK’s relatively high level of openness to foreign trade and products, comparatively small domestic furniture sector, and longer distances from the heartland of EU furniture manufacturing in Italy, Germany and Poland.

Fears of economic fallout from Brexit have led to an immediate and large devaluation of the British pound against other currencies. Throughout October, the pound has been trading at around $1.22 against the dollar, the lowest level for 31 years and 18% less than just before the Brexit vote. At times during the month the pound also dropped below the psychologically important €1.10 mark against the euro, its lowest level since March 2010 and 15% less than before the vote.

After a year of strong growth in 2015, the UK’s imports of wood furniture had levelled off at the higher level in the first half of 2016, prior to the Brexit vote. UK imports from other EU countries and from China had declined slightly during this period, but were continuing to grow slowly from the main tropical suppliers including Viet Nam, Malaysia, Brazil and Indonesia (Chart 4).

The impact of Brexit on UK high street retailers in the immediate aftermath of the Brexit vote seems to have been muted. The British Retail Consortium (BRC) reports no discernible impact on retail spending and shop prices stemming from the EU vote. The first three months after the referendum saw continuation of a two-year downward trend in overall retail sales growth. The one per cent year on year growth in the three months to September was below the 1.2% average growth in the twelve months leading up to the vote. Shop prices remain firmly in deflationary territory, falling 1.8% year on year in the three months following the vote.

The latest GDP data supports the general conclusion that the economy has not yet suffered damage from the Brexit vote, at least in the short term. Data from the UK Office of National Statistics shows that the economy grew by 0.5% in the three months to September, slower than the 0.7% growth achieved in the previous quarter but stronger than 0.4% growth in the first quarter. Annualised growth is currently at 2.3%, amongst the highest of rich western economies this year. The IMF now predicts that the UK will be the fastest growing of the G7 leading industrial countries in 2016.

However, the future implications of Brexit for the UK and the wider EU market for wood furniture remain very uncertain. Although some importers and retailers have been able to protect themselves in the short term through smart procurement and forward currency purchases, the pound’s devaluation is likely to have dampened UK imports of wood furniture and other timber products over the summer months and will continue to act as a drag in the months ahead. At some point in the near future, probably early in 2017, it is widely expected that the pound’s devaluation will begin to feed through into higher retail prices and slower sales.

Much press coverage on longer term impacts of Brexit emphasises the downside, notably uncertainty created for business investment and consumers, the potential for new tariff and non-tariff barriers in trade with the UK, and the possibility of rising labour costs if more stringent controls are imposed on immigration. None of this should be under-estimated, and politicians in both the UK and EU face a considerable challenge to reach an agreement that limits the economic and political damage.

But expectations in the British retailing community are not entirely negative. This is well illustrated in the speech by Richard Baker, the BRC Chairman, at an October meeting of major UK retailers to discuss their response to Brexit. Baker was realistic about the challenges of greater uncertainty, the weaker pound, and tighter controls on immigration. He observed that a huge proportion of the goods sold in the UK are sourced from outside the country, with the EU being by far the single biggest part of this trade. There is no clarity at all on how much customs duty will have to be paid on a huge range of items, both from within and outside the EU, after Brexit.

However, Baker also noted that “in my view there is good reason to believe that smaller, more agile government that is wholly focused on the needs of Britain has a good chance of being more successful than one that must endeavour to satisfy 28 member states and balance their frequently conflicting agendas”.

Baker also wondered whether “there is in fact potential for reduced costs of trading”, speculating that there may well be opportunities to reduce the burden on UK businesses currently imposed by the EU through rules on competition and state aid, environmental protection, workers’ rights, consumer protection and information, health and safety, data protection, food and other product safety, and so on.

Under the terms of the Great Repeal Bill announced by the UK Prime Minister in early October, the UK Government plans to adopt EU legislation wholesale. However, once the UK exits the EU, there will be a lengthy period of national consultation when the UK government, guided by the electorate, decides which rules to repeal, amend or retain.

Baker indicated that during this period, the BRC “will be campaigning for an outcome that enables retailers to offer great choice and value to their customers by ensuring access to quality, responsibly-sourced, safe products from all around the world, free of unnecessary costs and charges”. Specifically, the BRC will aim to “ensure that there are no new tariffs and that the costs of bureaucracy do not increase”.

Baker noted that that the UK retailer sector is the UK’s biggest importer and pays billions of pounds each year in customs duties. It therefore has a considerable stake in ensuring a favourable outcome. He noted that “one BRC member has calculated that the customs bill could quadruple without a trade deal with the EU and if the UK loses its privileged trading status with other countries. Any significant increase in tariffs will inevitably find its way into shelf prices”.

On the other hand, according to Baker, there may be opportunities to reduce tariffs where they currently exist. There may be potential, for example “for an extension to the Generalised Scheme of Preferences to allow more goods from developing countries to enter the UK free of duty. This would be good for shoppers, good for retailers and great for the UK’s commitment to a strong international development agenda”.

Furthermore, Baker asked, “Could the UK, as an independent trading nation, in fact find it easier and cheaper to trade beyond the borders of the Single Market with, for example, the United States?” In a reference to the extremely slow pace of negotiations of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) and the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) between the EU and the U.S. and Canada respectively, Baker asked “does a bi-lateral trade agreement need to take seven years with only two countries involved?”

It should be said that tariffs are not a particularly critical issue for external suppliers of wood furniture into the EU. EU import tariffs are already zero on all wood furniture with the exception of components and kitchen furniture which are subject to 2.7% tariff.

However, some suppliers of tropical wood would benefit from a reduction of tariffs or extension of the GSP framework by the UK. Tariffs of 4% to 5% currently apply to planed, sanded and finger-jointed sawn tropical timber. Hardwood veneers and plywood also attract tariffs of between 3% and 10%.

Baker’s comments also shows that UK businesses are not just looking to minimise the damage from Brexit, or waiting passively for politicians to come to terms, but are looking creatively at the new opportunities that may arise from Brexit.

If there is a so-called “hard Brexit” in which the UK fails to reach agreement with the rest of the EU and withdraws or is ejected from the single market – an event which could occur as early as 2019 – there will be severe economic fallout in the UK and, to some extent, other EU countries. But UK businesses would then have a very strong incentive to expand trade with countries outside the EU. This may be particularly significant for suppliers of wood furniture in the tropics whose main competitors in the UK market are manufacturers located in the EU.

Implications of IKEA’s drive to expand market share

The continuing expansion of IKEA, the world’s largest furniture company, is another factor driving change in the EU market for wood furniture. In 2015, IKEA’s sales increased by 11.2 % to €31.9 billion and the company booked a net profit of €3.5 billion, 5.5% more than the previous year. Growth was well distributed across IKEA’s markets and sales were highest in Germany, the US, France, the UK and Italy.

At the end of the 2015 financial year, IKEA boasted 328 stores in 28 countries, 27 Trading Service Offices in 23 countries, 48 distribution centres in 17 countries, and 43 IKEA industry production units in 11 countries. Much recent expansion has been in other regions, notably in South Korea and India, but the company is still heavily oriented towards Europe. Europe accounts for 229 Stores, 19 distribution centres, and 34 IKEA industry production units.

Of IKEA’s purchases of home furnishing articles from suppliers – both the company’s own industry production units and external suppliers – 60% of value derives from Europe, 35% from Asia, 3% from North America, 2% from Russia and 1% from South America. In terms of countries, China is now the largest single supplier to IKEA, accounting for 25% of purchases, followed by Poland (19%), Italy (8%), Sweden (5%) and Lithuania (5%).

IKEA is the largest single buyer of wood material in Europe, probably in the world. The company consumed 16.2 million cubic meters of wood (roundwood equivalent) in the 2015 financial year, up 4% compared to the previous year. Around 60% of this comprised solid wood and 40% board products. If paper and packaging is included, the company is estimated to need close to 20 million cubic meters of wood fibre every year.

Most of IKEA’s wood supply derives from Europe, the largest suppliers being Poland (around a quarter), Lithuania (7.5%), Russia (7%), and Sweden (6.5%). Swedwood, an IKEA subsidiary, handles production of all wood based furniture. To date, IKEA has been almost entirely reliant on wood owned and managed by other companies, but recently it has bought a few relatively small forest areas in Romania and the Baltic States in order to secure long-term access to sustainably managed wood at affordable prices.

In 2012, IKEA set an ambitious target to double sales value to €50 billion ($55 billion) by 2020. Since the company is also committed to lowering overall prices each year, that implies more than a 100% increase in sales volume. However, IKEA claims that this will not lead to a doubling in use of wood due to a strong focus on increased material efficiency in product design.

IKEA is committed to making every product with what it refers to as “democratic design” principles in mind. Democratic design seeks to find way to balance the often contrasting demands of form, function, quality, sustainability and a low price. An important component of this is a commitment to create a “circular IKEA” where products are designed to last as long as possible, for easy upcycling and recycling, and secondary materials are preferred to virgin raw materials.

Another component is to forge a closer link between the product designers and the operators of the machines on the factory floor. Although most IKEA products are still designed at Älmhult in Sweden or at IKEA’s product development centres in Asia, more and more are now being developed directly in the factory where the designers work closely with the production specialists and craftsmen to utilise existing technology, their experience and know-how to maximise each dimension of democratic design.

IKEA’s product ranges now bear witness to this approach to design, with potentially important implications for the use of wood, fashion and the wider furniture design community in Europe. For example, the tops of trees and other irregular pieces of wood that would formerly have been discarded as waste are now utilised to manufacture IKEA’s Norden series of tables. In IKEA’s Lacka series of coffee tables and for wardrobe doors, IKEA increasingly uses a board on a frame rather than a thicker piece of solid wood. IKEA’s Mockelby table is made of small pieces of jointed wood covered by a layer of veneer.

Similarly, IKEA’s Nornas line is described as “a modern collection in raw, untreated, high-quality pine from forests in Northern Sweden”. While this suggests utilisation of a potentially sensitive slow-growing forest resource, IKEA claim to have minimised the environmental footprint by ensuring that the technical specification closely matches the natural features of the raw material. The product is made from small logs that can be derived from thinning operations. The production process is adapted to accommodate boards in a wide variety of widths to maximize the utilization of the log. The product also makes a virtue of the numerous dark knots that characterise the raw material, showing them off to highlight the natural authenticity of the product.

Other, more subtle measures are used to improve material efficiency. For example, IKEA now more carefully controls the density of the particleboard used for the backs of products like wardrobes and dressers. Rather than use one sheet of particleboard of standard thickness, the company designs its boards to be thicker around the hinges and corners, and thinner toward the middle, which needs less support.

IKEA is not a major user of tropical wood and, in fact, has played a leading role over the last quarter century to drive European consumers towards the clean and light ‘Scandinavian look’, heavily dependent on softwoods and temperate hardwoods. And, due to the company’s very high profile, IKEA is inevitably a principal target for negative environmental campaigns whenever a tropical wood appears in any product line. One environmental group, Robin Wood in Germany, went so far as to test a wide range of IKEA products for tropical wood content and launched a highly critical public campaign following their identification of tropical wood fibre in paper supplied by the company.

Nevertheless, IKEA has not excluded tropical wood from their product range. The company’s Skogsta product line is made of acacia which, in line with their broader environmental strategy, seeks to maximise utilisation of the material. The product line shows off the natural colour variation in the wood, utilising both the light blond and dark shades of timber.

While IKEA does not exclude use of tropical wood in its product lines, the company is ratcheting up the procurement requirements imposed on all suppliers. Since 2000, IKEA has operated a supplier code of conduct for purchasing all products, materials and services referred to internally as IWAY. It sets out our minimum requirements for suppliers, covering environment, social and working conditions, and it is a pre-condition for doing business with the company. IKEA employs 87 IWAY auditors to carry out around 2,000 audits per year.

For timber supplies, IKEA has set a target to ensure that 100% derives from “more sustainable sources” – currently defined as FSC certified or recycled wood – by 2020. In 2015, IKEA reported that 50% of wood used – somewhere in the region of 8 million m3 – derived from these sources. To meet all their targets, IKEA will likely have to find at least another 10 million m3 of “more sustainable” timber every year after 2020.

Due to the volumes involved, IKEA’s timber procurement policy has the power to drive wider changes in the wood supply chain. In practice, IKEA have been a major factor behind the moves to reduce the length of wood furniture supply chains, increase dependence of the European wood furniture sector on local wood supplies, and to discourage a movement by manufacturers to other regions.

This is all made explicit in IKEA’s corporate sustainability strategy which states: “in IKEA purchasing, we want to exploit our competitive advantage of economies of scale. Volume is our best friend. Our large volume approach enables us to invest in efficient industrial production set-ups and focus on affordability, accessibility, sustainability and quality. To enable professional purchasing, we continuously shorten the distance between customers and suppliers, with fewer people involved. By using an end-to-end perspective, we can ensure better products faster at a low price. One example is locating the material supply close to the production, and/or locating production closer to sales markets. Thereby we can reduce transportation cost and CO2 impact in the value chain”.

IKEA Global Forestry Manager Anders Hildeman agreed, but also said that other keys to success for FLEGT-licensed timber and products in such large markets as furniture and retail would be availability and momentum.

“Industry take-up of FLEGT-licensed products will depend on achieving critical mass, so once those first countries start supplying them, we need others following quickly behind,” he said. “So, while I don’t underestimate the challenges involved, my message would be let’s get on with it!”

Illegality risk assessment and due diligence were already integrated into their operations, and they are also all working towards 100% certified sustainable sourcing. What the EUTR did do, however, was prompt renewed scrutiny and reappraisal of existing systems and a step up in communication on illegality risk. “The Regulation has specific due diligence requirements we had to accommodate,” said Mr Hildeman. “We also undertook extensive EUTR training and, I believe, it also helped us strengthen legality messages to suppliers.”

Occasionally we’ve stopped sourcing from companies when documentation is inadequate, but we work with them and restart trading when problems are resolved,” said Mr Hildeman. “I understand some operators dropped suppliers where due diligence was particularly challenging, but that wasn’t the EUTR’s objective. It disincentivises suppliers from raising legality standards in places which need most support. It’s an area the EU should examine.” If we harmonise legality definitions internationally, it could give all schemes momentum and create a ripple effect into other markets,” said Mr Hildeman. “It would also further benefit the battle against organised crime, which operates in the illegal trade globally.”

Mr Hildeman believes that once FLEGT-licensed timber is available in the EU market, the initiative could also have value as evidence of risk mitigation under other market legality regulation, such as Lacey and the AILPR.

PDF of this article:

Copyright ITTO 2020 – All rights reserved