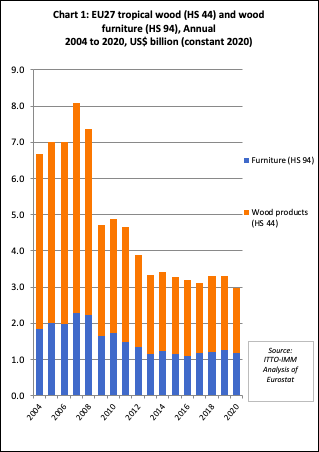

Total EU27 (i.e. excluding the UK) import value of tropical timber and wood furniture products was US$2.99 billion in 2020, 9% less than the previous year. This is a significantly higher level of import than forecast when the first waves of the COVID-19 pandemic hit the continent early in 2020. It was, however, the lowest level in recent decades and represented a further decline in a market that has been severely restricted ever since the financial crises (Chart 1).

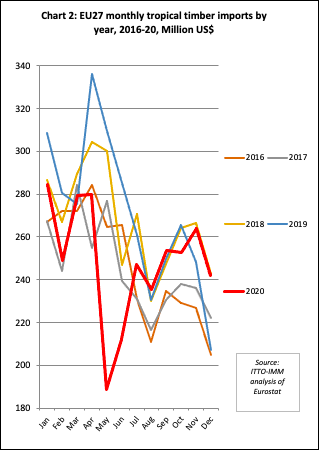

Total EU27 tropical wood and wood furniture import value in December was US$242 million, an 8% fall compared to the previous month. However imports during December were relatively high for that month, being 17% more than the same month in 2019, as products continued to arrive after delays earlier in the year (Chart 2). Consumption was holding up much better than expected across many sectors, from construction and DIY to merchants and furniture makers. In fact material supply has been more of an issue than demand, particularly due to lack of container space and soaring freight rates. With global container distribution disrupted by the pandemic, shippers out of Asia have been naming their price. Importers report five- and six-fold rises in container rates since mid-2020.

Decline in EU27 imports recorded for all tropical wood product groups

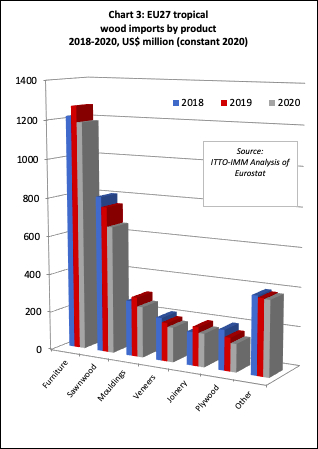

Unsurprisingly, EU27 imports of all the main tropical wood products fell in 2020, but in each case the decline was less dramatic than expected earlier in the year when the scale of the pandemic and associated lockdown measures was just becoming apparent. During the year, EU27 import value of wood furniture from tropical countries declined 7% to US$1185 million, while import value of tropical sawnwood declined 13% to US$659 million, tropical mouldings were down 15% to US$263 million, veneer down 10% to US$179 million, joinery down 14% to US$172 million, plywood down 16% to US$144 million, marquetry and ornaments down 14% to US$68 million, and logs down 25% to US$41 million. Import value of tropical flooring actually increased slightly, up 3% to US$62 million (Chart 3).

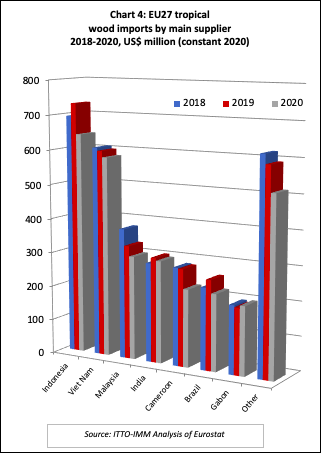

Indonesia maintained its position as the largest single supplier of tropical wood and wood furniture products to the EU27 in 2020 despite a 12% fall in value to US$643 million. Imports were down 3% to US$581 million from Vietnam, 9% to US$302 million from Malaysia, 3% to US$298 million from India, 20% to US$226 million from Cameroon, and 15% to US$223 million from Brazil. However, imports from Gabon increased 3% to US$200 million in 2020 (Chart 4).

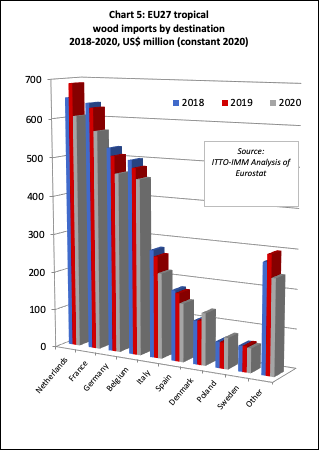

Import value fell into all six of the largest EU27 destinations for tropical wood and wood furniture products in 2020. Import value was down 12% to US$606 million in the Netherlands, 9% to US$570 million in France, 9% to US$465 million in Germany, 6% to US$455 million in Belgium, 16% to US$221 million in Italy, and 14% to US$151 million in Spain. However, import value increased in Denmark, by 18% to US$134 million, and in Poland, by 20% to US$80 million. Import value in Sweden declined, but by only 6% to US$63 million (Chart 5).

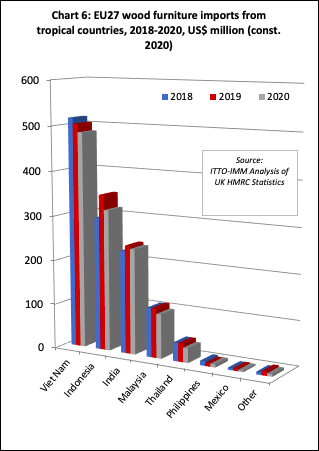

EU27 wood furniture imports from Vietnam close to last year’s level

In the furniture sector in 2020, EU27 imports from Vietnam were down only 4% to US$484 million in 2020, having recovered strongly from a sharp dip during the first lockdown. Imports from Indonesia were down 9% to US$317 million in 2020, although this compares with a strong performance in 2019 and imports were still higher than in 2018 (Chart 6).

EU27 imports of wood furniture declined sharply from Malaysia and Thailand in 2020, respectively down 11% to US$99 million and 21% to US$33 million. However, imports from the Philippines increased 5% to US$7.0 million.

EU27 imports of wood furniture from India were down only 3% to US$236 million in 2020. Partly due to supply side issues, imports from furniture from India almost came to a complete halt in May last year but rebounded very strongly in the second half of 2020 when they were at record levels for that time of year.

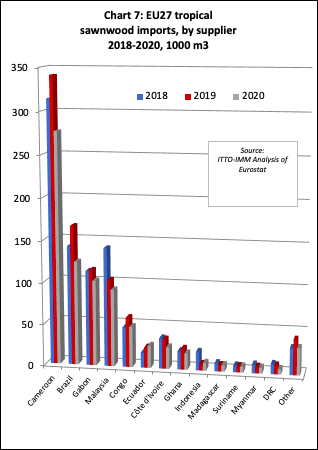

EU27 tropical sawnwood imports at record low in 2020

In quantity terms, EU27 imports of tropical sawnwood declined 18% to 783,500 cu.m in 2020, the lowest level ever recorded for this group of countries (well below the previous low of 836,000 cu.m in 2017). Imports fell sharply from all major supply countries; down 19% to 276,800 cu.m from Cameroon, 26% to 124,000 cu.m from Brazil, 11% to 102,100 cu.m from Gabon, 11% to 92,100 cu.m from Malaysia, 18% to 48,500 cu.m from Congo, 27% to 25,700 cu.m from Côte d’Ivoire, and 22% to 19,400 cu.m from Ghana.

However Ecuador bucked the downward trend, with EU27 imports of sawnwood from the country rising 10% to 26,600 cu.m in 2020, much destined for Denmark and driven by booming demand for balsa for wind turbines. Imports of sawnwood from Indonesia also increased sharply in 2020, by 21% to 9,000 cu.m, but this follows a 66% reduction in 2019.

There was a slight 2% rise in sawnwood imports from Madagascar to 7,400 cu.m, while imports from Suriname fell only 2% to 6,800 cu.m. Imports were down 12% to 6,600 cu.m from Myanmar. The largest percentage fall in imports was from DRC, down 39% to only 6,200 cu.m. (Chart 7).

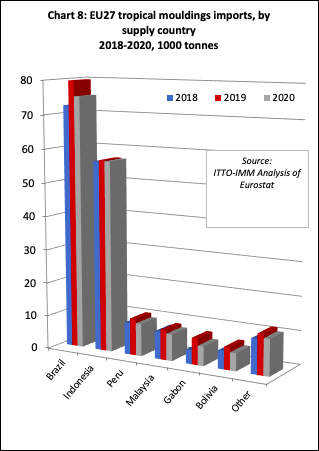

The decline in imports of tropical sawnwood in 2020 was mirrored by a similar decline in EU27 imports of tropical mouldings/decking. Imports of this commodity were down 6% overall at 171,300 tonnes, falling 6% from Brazil to 75,200 tonnes, 1% from Indonesia to 56,700 tonnes, 11% from Peru to 9,700 tonnes, 12% from Malaysia to 11,500 tonnes, 27% from Gabon to 5,800 tonnes, and 21% from Bolivia to 5,300 tonnes (Chart 8).

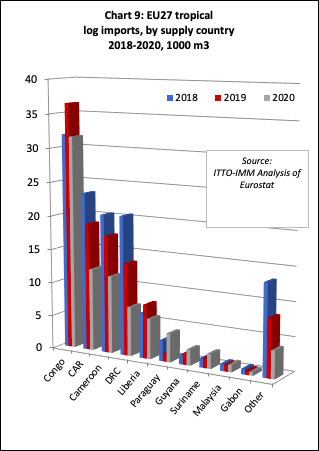

EU27 imports of tropical logs were down 24% to 82,900 cu.m in 2020. Imports held up reasonably well from the Republic of Congo, down 13% to 31,600 cu.m, but fell sharply from all other leading African supply countries including Central African Republic (-35% to 12,200 cu.m), Cameroon (-34% to 11,500 cu.m), DRC (-47% to 7,300 cu.m), and Liberia (-25% to 5,900 cu.m). However, there was a significant rise in imports from three smaller suppliers in South America; Paraguay (+262% to 4,200 cu.m), Guyana (+37% to 2,300 cu.m), and Suriname (+54% to 2,200 cu.m) (Chart 9).

EU27 tropical veneer imports from Gabon on the rise despite pandemic

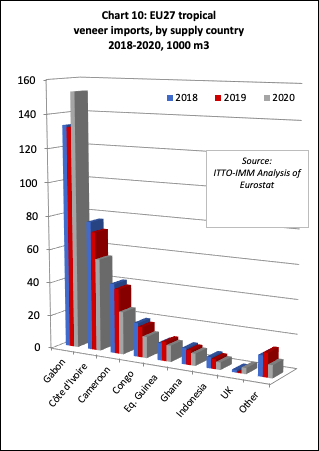

EU27 imports of tropical veneer declined 7% to 278,700 cu.m in 2020. Imports from Gabon bucked the wider downward trend, the EU27 importing 152,800 cu.m from the country during the year, 16% more than in 2019, mainly destined for France. Veneer imports declined from all other major tropical suppliers, including Côte d’Ivoire (-22% to 55,200 cu.m), Cameroon (-35% to 25,400 cu.m), Republic of Congo (-30% to 12,700 cu.m), Equatorial Guinea (-15% to 9,700 cu.m), Ghana (-16% to 7,300 cu.m), Indonesia (-23% to 4,400 cu.m). (Chart 10).

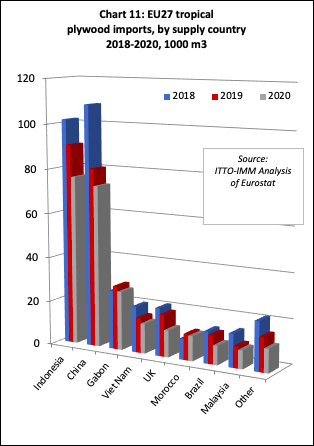

Although there were signs of an uptick in the pace of EU27 imports of tropical hardwood faced plywood in the last quarter of 2020, total imports of 239,900 cu.m for the whole year were still down 15% compared to 2019. Imports fell from all the leading supply countries including Indonesia (-16% to 76,200 cu.m), China (-9% to 72,900 cu.m), Gabon (-8% to 26,500 cu.m), Vietnam (-14% to 13,500 cu.m), Morocco (-5% to 11,200 cu.m), Brazil (-33% to 8,600 cu.m), and Malaysia (-14% to 8,300 cu.m). EU27 imports of tropical hardwood faced plywood from the UK – a re-export since the UK has no plywood manufacturing capacity – declined 36% to 12,100 cu.m in 2020 (Chart 11).

EU27 tropical flooring imports rise while other joinery imports decline

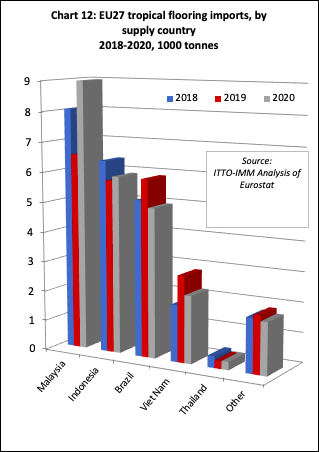

Given the situation in the wider market, one of the least expected trends in 2020 was a slight recovery in EU27 imports of tropical flooring products. This follows a long period of continuous decline. Imports increased 4% to 24,200 tonnes during the year, the gain due primarily to a 37% rise in imports from Malaysia to 9,000 tonnes, mostly destined for Belgium. Imports from Indonesia also increased slightly, by 3% to 5,900 tonnes. However, imports declined sharply from Brazil, down 16% to 5,000 tonnes and Vietnam, down 22% to 2,300 cu.m (Chart 12).

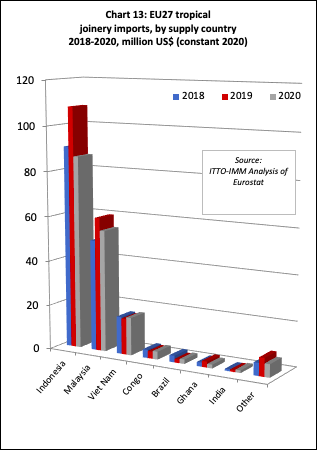

EU27 import quantity of other joinery products from tropical countries, which mainly comprise laminated window scantlings, kitchen tops and wood doors, declined 14% to 171,800 tonnes in 2020. Imports were down 20% to 86,400 tonnes from Indonesia, 9% to 54,400 tonnes from Malaysia, and 38% to 1,700 tonnes from Ghana. However, imports increased by 5% to 16,900 tonnes from Vietnam, 11% to 3,600 tonnes from the Republic of Congo, 26% to 2,000 tonnes from Brazil, and 41% to 1,200 tonnes from India. (Chart 13).

Paris 2024 Olympics’ timber commitment excludes tropical suppliers

Timber use in France has been given a massive boost by the French government’s commitment to ensure that the Paris 2024 Olympics is the first “climate positive” sports event and by their desire to ensure this leaves a lasting legacy in the French construction sector.

But this commitment will play no role to support sustainable forestry in the tropics unless the existing prohibition on use of tropical timber for Olympic developments is removed.

On 16 March, the Board of Directors of the Paris 2024 Olympics gave their official seal of approval to the Games’ climate strategy which, in line with the Paris Agreement, aims to considerably reduce greenhouse gas emissions and offset in excess of its residual emissions linked to the event.

A key aim is to greatly reduce emissions during the construction phase, notably for the 314,000m2 of accommodation and other developments for the athletes’ village and the 1,300 apartments being built for the media.

This should be a huge opportunity for the timber sector, not only because of the role it can play in mitigating carbon emissions directly associated with the Olympic developments but also due to the potential influence of Olympic green procurement requirements on future building regulations in France.

The good news for the timber sector in France is that there is already strong recognition at the highest level of government of its significant carbon mitigation benefits. The French government announced in early 2020 that any building in the Olympic development that rises more than eight storeys must be built entirely from timber.

Partly inspired by this Olympic vision, the French government also announced that from 2022 all new public buildings in the country must be built from at least 50% timber or other natural materials.

The French timber sector has formed a body, France Bois 2024, to promote wood use and press for the Olympics to live up to commitments on environmental impact generally and use of natural raw materials in particular.

The ‘Cahier de Prescriptions d’Excellence Environnementale’ (Environmental Excellence Prescription” referred to as the CPEE[1]), which is developed by the Paris Olympics delivery body SOLIDEO and is binding on all contractors involved in Olympic Village development, includes some positive aspects for promotion of sustainably sourced timber.

The CPEE emphasises the importance of “la traçabilité écologique des matériaux” and states that the challenge is to initiate an “approche globale” (as in “universal” or “holistic” rather than simply “global”) to ensure materials are chosen that reduce carbon emissions and protect biodiversity.

Therefore, the meaning of “la traçabilité” in the context of the CPEE implies much more than just identifying the place of origin of materials. It also requires a full accounting of environmental impacts across the product life cycle. Wood typically performs extremely well compared to other materials when such comprehensive accounting is undertaken in a fair and credible manner.

The CPEE also includes a requirement to “promote a diversity of species and/or a diversity of hardwood and softwood varieties in construction: in particular, give priority to solid wood from various hardwoods in the non-structural elements of buildings.”

This is an encouraging sign of growing awareness of the intrinsic value of expanding timber use away from a few well-known species to accommodate the full diversity of timbers that forests are able to produce.

However, as so often the case with public procurement requirements, these objective criteria in the CPEE are undermined by a series of other requirements driven more by political considerations, protecting certain supplier interests and brands, than by scientific assessment of the environmental impacts of different materials.

The CPEE requires that at least 30% of wood used for the development of the Olympic Village derives from mainland France. All wood used must be either FSC or PEFC certified. A serious concern for tropical suppliers, indeed for a large proportion of non-EU suppliers, is a specific prohibition on the use of wood of tropical and boreal origin from outside the EU.

The only exception to this prohibition is if non-EU tropical or boreal wood is required for “fire safety reasons”, in which case it must be FSC certified. Even in these limited circumstances, there is no recognition for PEFC certified tropical or boreal timber from outside the EU. There is no recognition at all for FLEGT licensed timber anywhere in the CPEE requirements.

Tropical trade associations protest against tropical timber discrimination

An open letter signed by several tropical timber trade and industry associations has been sent to SOLIDEO Executive Director General Nicolas Ferrand, protesting that the CPEE prohibition on tropical timber use is contrary to EU competition rules and has no clear environmental rationale.

Signatories to the letter are the Tropical Timber Technical Association (ATIBT), the French timber traders federation Le Commerce du Bois (LCB), the Union des Industries du Panneau Contreplaqué (UIPC), the Malaysian Timber Council (MTC), the European Sustainable Tropical Timber Coalition (STTC) and the Union des Métiers du Bois de la Fédération Française du Bâtiment (UMB-FFB).

According to the letter, the requirement ‘seem[s] to contravene the principle of free competition of products – a founding principle of the EU’. Nor, they maintain, is it based on ‘clearly defined environmental protection requirements’.

“SOLIDEO’s position [also] does not take into account recommendations of the French Ministry of Ecological Transition (MET), or NGOs, such as the WWF, which, subject to wood being supplied from forests certified for sustainable management, do not exclude geographical origins,” the letter states.

The letter also points to a statement in MET’s 2020 procurement guide, which supports use of sustainable tropical timbers and maintains that if these are boycotted ‘tropical forests lose their value [in generating] foreign currency’, resulting in ‘strong pressure to clear them for agropastoral or agroindustrial purposes’.

On releasing the letter, ATIBT and LCB said that the issue has been discussed with authorities in Cameroon, Gabon, Republic of Congo and Malaysia ‘in anticipation of a future concerted approach at the political level’.

Civil society calls on EU to extend support for FLEGT

A wide range of civil society organisations involved in the FLEGT process have issued a statement in response to recent presentations at various webinars by EU Commission representatives of their preliminary conclusions of the results of the ongoing Fitness Check of the FLEGT and EUTR regulations.

As reported in the previous edition of TTMR (Vol 25, No.7 1st–15th April 2021), the EC questioned the effectiveness of FLEGT licensing, a core component of the VPA process to date, and EUTR as measures to reduce illegal logging and trade.

Under the heading “Raising the bar”, the statement signed by around 50 civil society organisations from Asia and the Pacific, the Americas, Europe, and West and Central Africa, notes that “the [FLEGT] Action Plan remains a relevant and innovative response to the challenge of illegal logging”.

The civil society organisations emphasise that the Action Plan “has improved forest governance in partner countries and has put the issue of illegal logging at the forefront of policy concerns. It is strengthening legal and institutional frameworks, and increasing multi-stakeholder dialogue and participation, and transparency in partner countries”.

Specifically on the VPAs, the civil society organisations suggest these have “directly and positively impacted forest management and helped timber-producing countries and companies to improve their environmental practices and reputation”.

In a reference to EUTR, the civil society organisations suggest that “FLEGT has also created a level playing field and reduced demand for illegal timber in the EU”.

On the FLEGT Fitness Check, for which the EU Commission’s final evaluation report is still due, the civil society organisations “expect that the results will provide a balanced and comprehensive assessment of both regulations that includes the views of stakeholders, such as CSOs, both in the EU and in partner countries”.

The civil society organisations believe that the “EU’s response will provide an opportunity to strengthen FLEGT and the EUTR, while maintaining the integrity of VPAs to encourage the legal timber trade and more inclusive socio-economic benefits for producing countries.”

The statement concludes with a series of recommendations, including that: the EU to invest in VPAs; the EU keeps FLEGT licensing as a key element of VPAs; obstacles to the issuance of FLEGT licences – including capacity gaps, lack of resources, weak governance, and insufficient political support – are tackled effectively; EUTR enforcement is strengthened; the issue of corruption is given greater priority; and the EU to promote legality as the first step to sustainability.

The civil society statement is at: https://www.fern.org/fileadmin/uploads/fern/Documents/2021/Raising_the_bar_CSOs_statement-EN.pdf

[1] MIS received a copy of the CPEE but it has not been made publicly available on the SOLIDEO website. The SOLIDEO English website is at https://www.ouvrages-olympiques.fr/en/commitments/sustainable-city

PDF of this article:

Copyright ITTO 2021 – All rights reserved