The rebound in UK imports of tropical wood products as the first wave of the pandemic receded in summer last year slowed in the last quarter of 2020 as the country, like much of the rest of the Europe, reimposed lockdown measures in response to the second larger wave which hit at the start of the winter months. In addition to a slowdown in overall UK business activity at the end of 2020, there are also reports of severe supply problems in the UK building sector, including for products imported from South East Asia and China, due to limited container space and rising freight costs.

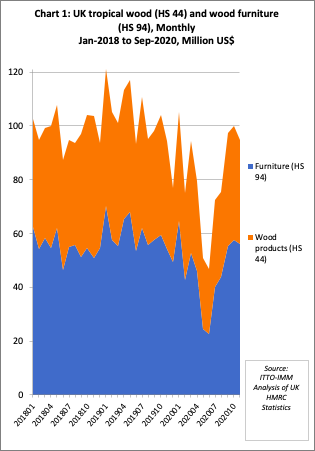

Total value of UK imports of tropical wood and wood furniture months increased only slightly from US$98 million in October to US$100 million in November, but then receded again to US$95 million in November (Chart 1). Total UK tropical wood and wood furniture imports in the 11 months to November 2020 were US$892 million, 23% less than the same period in 2019.

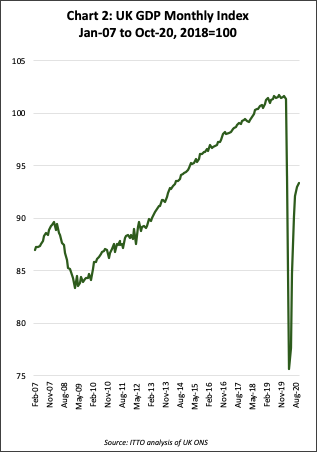

When the recovery in the UK economy began to slow in the last quarter of 2020, GDP in October 2020 was still 8% percentage points down compared to February 2020 just prior to the pandemic (Chart 2). The IMF now estimates that UK GDP contracted 10% for the year in 2020, the biggest fall of any G7 country, and forecasts that GDP will expand by 4.5% this year, down 1.4% points from the IMF’s previous 5.9% growth forecast published in October.

According to IMF, the recent acceleration of the UK’s vaccination programme is not expected to give an extra boost to UK growth until 2022 when the forecast growth rate has been upgraded by 1.8 percentage points to 5%. This aligns closely with the latest forecast by UK Treasury’s independent spending watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), which also indicates that the UK economy will not return to its pre-crisis level until the end of 2022, at the earliest.

Strong UK construction activity and freight problems lead to severe timber shortages

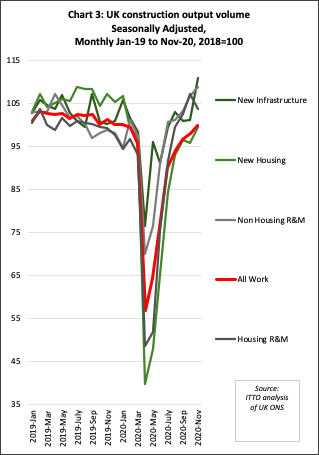

A positive factor for the UK timber trade in 2020 was that the initial downturn in construction sector activity, which is a key driver of timber demand, during the first “great lockdown” was short and followed by a stronger rebound than other areas of the economy. This rebound was losing momentum in the last quarter of 2020, but not before overall construction activity was nearly back to pre-pandemic levels. Repair and maintenance activity, both for housing and non-housing, an important driver for hardwood demand, was actually slightly higher than before the pandemic (Chart 3).

IHS Markit Purchasing Managers Index data for UK construction in December was also positive showing that the rebound in UK construction activity continued during the month. According to IHS Markit, new order levels for UK construction increased for the seventh successive month.

But according to IHS Markit, the combination of the pandemic and Brexit meant that supply chains to the UK construction sector were “groaning at the seams and delivery times increased to the most dramatic extent for six months. Low availability for finished products and raw materials as a result of port disruptions added to builders’ woes as suppliers named their price for goods in acutely short supply and input price inflation increased to its highest level since April 2019”.

Reports from UK trade associations and business groups highlight the development of a short supply situation for building products in the UK driven by a combination of strong demand and COVID and Brexit related supply problems. According to the Builders Merchants Federation (BMF), which represents 760 merchant and suppliers companies in Britain, high demand, escalating prices for shipping and delays at some British ports were all having a “major impact” on the supply chain.

John Newcomb, chief executive of BMF, said: “Merchants have seen an exceptional demand for building materials since the first lockdown. In November, we saw an average growth of 9 per cent across our membership compared to the same time last year. Looking at December’s figures, we are predicting that growth could be double digits, and that’s unprecedented.” More specifically on timber, it was noted that “prices in the UK have risen by an average of 20%”.

Housebuilders are racing to complete thousands of homes ahead of deadlines for the UK government’s Help to Buy scheme and stamp duty holiday in February and March, two measures introduced in 2020 to support the economy during the pandemic. Some of Britain’s biggest builders including Persimmon and Taylor Wimpey have reported record order books for the year ahead, as buyer demand shows no sign of abating.

A spokesman for the Home Builders Federation, which represents UK housebuilders, said: “Demand remains strong and whilst builders are committed to completing homes and increasing supply some constraints have emerged. Shortages of certain products are being experienced, alongside Covid-related delays but it is hoped these will be short term.”

The BMF said there has been a surge in costs of building products shipped in containers from the Far East, which was already a concern at the end of last year. Mr Newcomb said: “We continue to see issues with the availability of products imported in containers, mainly from the Far East”.

Container freight rates from Asia to the UK increased almost fourfold between November and the end of January to reach $10,000 for a 40ft unit for the first time, amid a global rebound in demand for consumer goods and materials, ships mothballed with their containers and crew and congestion across UK ports, where many empty containers have been left stranded making carriers particularly reluctant to take bookings for the UK .

The global rebound in shipping demand has been compounded by Britain’s hurry to stock up on materials and goods before the Christmas season and the severing of ties with the EU. This left many shipping containers stranded by warehouses and on the quayside of ports across the UK and Europe, after the influx of freight at the end of last year.

“Thin” Brexit deal does little to reduce UK costs of trading with the EU

The Brexit transitional period came to an end on 31st December when the UK left the EU single market. Contrary to expectations of a ‘no-deal’ – heightened earlier in December owing to continuing differences on the “level playing field” for competition, fisheries, and dispute resolution – an “EU-UK Trade and Co-operation Agreement” was eventually signed on 24th December. This combines a Free Trade Agreement with an overarching governance framework.

The signing of the deal means that the worst consequences of a “no-deal” scenario have been avoided, notably that there will be no tariffs imposed on bilateral trade between the EU and UK and there is an agreed governance structure for refining the details of future trade relations in specific sectors and for arbitration in the event of disputes. However, it does not alter the fact that the UK has left the single market and the days of “frictionless” trade between the UK and EU are over.

What this means in practice is now becoming apparent. The deal is notably thin, not covering the 80% of the UK economy accounted for by services and, while providing for zero-tariff trade, it does not exempt UK companies from the red tape associated with a customs border, including the need to handle customs declarations for imports and exports.

In the first few weeks of January, hundreds of trucks a day are being fined or turned away at cross-channel ports because they do not have the right paperwork, according to UK border officials in their reports to UK government. At the worst point during January, one in five lorries bound for the EU from the UK was turned back from the UK border.

This is having a severe knock-on effect. Many companies on both sides of the border have stopped exporting to avoid getting caught by new customs regulations and because of significantly higher transaction costs. At the end of January, the UK Road Haulage Association (RHA) said that freight exports to the Continent are still significantly down on expected levels nearly a month after the end of the transition period.

The RHA also warned that European hauliers, who make the bulk of the deliveries into the UK, were starting to reject UK-bound shipments. In addition to the delays and extra paperwork, these trips are now much less profitable because of a 40% decline in UK goods being sent to the EU since Brexit and many lorries returning empty. According to the RHA, new requirements for COVID tests are also very unpopular and having an effect on the number of hauliers prepared to make the trip.

The worst predictions for chaos and massive tailbacks at cross-channel ports, leading to shortages in UK supplies of essential goods such as foods and pharmaceuticals, were avoided in January as companies had stockpiled goods in anticipation of a hard Brexit. However there is now rising concern that the logistical problems in UK trade with the EU will worsen as stockpiles have been depleted and cross-Channel trade is due to pick up in February and March.

Considering the longer-term implications, the UK tax office (HM Revenue & Customs – HMRC), stated in evidence presented this month to the UK parliamentary committee on Brexit impacts, that British businesses will spend £7.5 billion a year handling customs declarations for trade with the EU — as much as they would have done under a no-deal Brexit. Jim Harra, chief executive of HMRC told MPs that the number of customs forms needed to trade with the EU under the Brexit deal “is not materially different from a no-deal situation”.

Mr Harra said that revenue estimates from October 2019, which found that the cost of no-deal to UK and EU business would be £15 billion a year, still held true under the deal, with half the bill landing on each side. HMRC’s impact assessment said that British businesses would need to handle 215 million more import and export declarations a year.

The complexity of new “rules of origin” has proved highly disruptive for many UK businesses, particularly those that use the UK as a distribution hub for the rest of the EU. The trade agreement only allows for duty and quota free trade between the UK and EU if exports meet stringent content requirements. Manufacturers must use a specific and high proportion of ingredients or parts made in the UK or the EU, the actual percentage varying depending on the product group.

This means that manufacturers exporting to the EU from the UK, and vice versa, must now be able to prove where all the parts came from. Manufacturers faced with similar free trade deals will often choose to accept the cost of the tariff to avoid the cost of all the paperwork.

UK trade relations after Brexit

Having achieved Brexit, the question now arises, what exactly does the UK government want to do with it? Given the additional costs and obstacles to trade with the country’s nearest neighbours and largest overseas customers, which are self-evident, the UK now needs to find some benefits.

For the past 45 years, Britain’s economic model has been clear: to make itself the most attractive destination for investment by firms looking for a hub for their European operations. As businesses are discovering, that model can no longer be sustained now that Britain is outside the EU’s single market and customs union. The UK government has yet to clearly articulate what model it believes should take its place to kickstart the business investment essential to any sustained recovery.

One objective is apparent: to encourage greater direct UK trade with a wide range of countries outside the EU. A key idea behind Brexit was to give the UK greater freedom to negotiate trade agreements with partners outside the EU that more directly benefit UK interests.

Certainly, the UK has been busy securing trade agreements since the Brexit decision. In the last 2 years, the UK has agreed trade deals covering 65 countries outside the EU. However, nearly all these just roll-over existing EU agreements and largely replicate the terms of trade that the UK previously enjoyed as part of the EU.

An agreement signed with Japan in October was the first to differ from an existing EU deal, going further in areas such as e-commerce and financial services, but according to Dr Minako Morita-Jaeger, International Trade Policy Consultant and Fellow at the University of Sussex: “while the Agreement has a certain political significance, its economic impact is likely to be very small. This is because it contains very limited improvements relative to the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA).”

The same is true of the UK-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement (UKVFTA), signed on 29th December, which also inherits most of the contents of the EU-Vietnam FTA (EVFTA), with only minor differences in relation to the UK’s commitments to tariff exemption for a limited range of Vietnamese agricultural products and differing commitments from Vietnam to opening the service market for British businesses.

Potentially more significant, and directly relevant for tropical wood suppliers, was the announcement in January by Liz Truss, the UK Trade Secretary, that the UK will shortly submit a formal request to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the free trade area comprising Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam.

The UK government has taken other steps to integrate with Asia’s regional blocs following its successful bid to become a Dialogue Partner of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). As a Dialogue Partner, the UK gains high-level access to ASEAN, alongside enhanced practical cooperation on various policy issues with the regional bloc. It also enables the UK to join other important dialogue partners, including the US, China, and India.

On the other hand, the UK government’s hopes of striking an early trade deal with the US — seen as one of the biggest prizes of Brexit — have faded after new warnings that such a deal would not be a priority for President Biden’s new administration. While the UK government claims that much of the work needed to secure a trade deal with the US has been done already, it has also admitted that an agreement is unlikely in 2021.

The most difficult areas of a UK-US deal — including agriculture and pharmaceuticals — are still unresolved and in any case the US is now more likely to prioritise a possible EU trade deal. The UK’s hope of facilitating greater trade with the US may now lie in the Biden administration’s decisions on CPTPP participation.

Little demand for “regulatory divergence” after Brexit from UK business

In addition to trade agreements, the UK government is consulting business leaders to provide ideas for so-called “regulatory divergence”; ways and means by which UK businesses may be made more internationally competitive by moving away from the EU’s regulatory regime. But here again there are no easy options or quick wins.

According to The Times, “the government’s problem is that businesses aren’t clamouring for Britain to diverge from EU rules. Rather the opposite….no one is demanding a watering down of employment and environmental regulations”. On the contrary, they are keen to abide by rules which are already well embedded into their business operations, that are demanded of their large customers in the EU, and any move to deregulate now carries the risk that the EU will retaliate by putting up additional barriers to trade. The Times concludes “the clamour in many sectors right now is not for divergence but convergence”.

It is still early days and perhaps in time new opportunities will emerge from Brexit for businesses in the UK as they adjust to the new trading regime and are, in effect, forced to increase their global competitiveness as they no longer have friction-free access to the large EU market. However, at present, it is hard to see how the new opportunities will be sufficient to offset the significant new obstacles imposed on trade with the UK’s nearest neighbours and largest export markets. In practice, the pressure from UK businesses is likely to be on retaining high levels of access to the EU market, even at the price of foregoing divergence with EU rules.

Implications of Brexit on demand for tropical wood in the UK

The long term effects of Brexit on UK imports of tropical wood products are still far from certain. At present, even the short term effects are obscured by the unprecedented disruption to supply chains, shipping operations and markets during the COVID pandemic.

However, it seems likely that, despite the agreement of a trade and co-operation agreement with the EU, the relative competitiveness of EU-based suppliers of wood and wood furniture products that previously benefitted from completely frictionless trade will be reduced in the UK market. Tropical suppliers will be competing on a more level playing field in this market.

Furthermore, the early signs of serious disruption in the trade between UK distributors and large hardwood traders in continental Europe – notably in Belgium and the Netherlands – has some potential to encourage once again more direct imports of tropical woods into the UK.

On the other hand, the ability of UK importers themselves to distribute tropical wood products across the EU is now much diminished. Furthermore, the potential gains due to tropical suppliers increased competitiveness in the UK may well be insufficient to offset the longer term drag on economic growth now that the UK has left the single market.

The UK government’s own 2018 analysis of the impacts of various different UK-EU trading relations following Brexit suggests that in the scenario closest to the actual outcome – a free trade agreement with tariffs on goods and non-tariff barriers equal to those in an average trade deal with the EU – the UK economy will be between 4.9% and 6.7% smaller fifteen years from now compared to continued EU membership.

Other implications of Brexit for tropical wood supplies in the UK were discussed in the December market report (ITTO TTMR Volume 24 Number 23, 1-31 December 2020 pages 27-30). The conclusions drawn there with respect to introduction of the UK’s new “Global Tariff” regime, the due diligence requirements of UKTR compared to EUTR, construction product standards, and phytosanitary requirements, are unaltered by the details of the EU-UK deal signed on 24 December.

UK tropical wood furniture imports down 23% to November last year

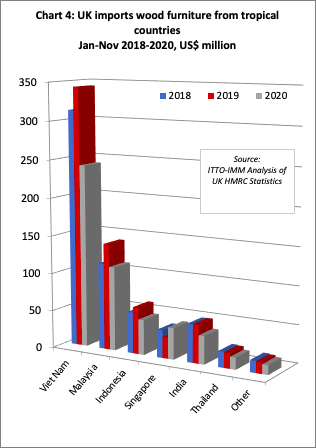

Overall UK imports of tropical wood furniture products in the eleven months to end November last year were USD506 million, 23% less than the same period in 2019. Imports gained momentum during October, rising to USD57.7 million compared to USD55.3 million in September, but then slowed a little to USD56.3 million in November.

Comparing the first eleven months of 2020 with the same period last year, UK imports of wood furniture declined sharply from all the leading tropical supply countries (Chart 4). Imports from Vietnam were down 30% to USD242 million, imports from Malaysia fell 21% to USD111 million, imports from Indonesia declined 25% to USD46 million, imports from India fell 26% to USD37 million and imports from Thailand were down 22% to USD16 million. In contrast, there was a 50% rise in imports from Singapore, to USD41 million.

The current quantity and direction of international trade in furniture is heavily influenced by freight issues. In an article in the Guardian newspaper on 27 January, Vincent Clerc, chief commercial officer for Maersk, the world’s biggest shipping company, is quoted as saying there are “simply not enough containers in the world to cope with the current demand”. He said that recent lockdowns in the UK and across Europe may even spur further online purchases of consumer goods including furniture for “at least for some weeks … It is really crazy how much we are moving at the moment, huge amounts,” he said.

The Guardian refers to one factor that might be driving recent growth in UK furniture imports from Singapore, noting that “Giant container carriers left off the coast of Singapore during the most stringent coronavirus measures last spring have already re-entered the shipping market to help ship containers to Europe”.

Pace of UK tropical wood products imports slows in November

UK imports of all tropical wood products in Chapter 44 of the Harmonised System (HS) of product codes in the month of October were USD42.3 million, the same level as in September, but declined to USD38.6 million in November.

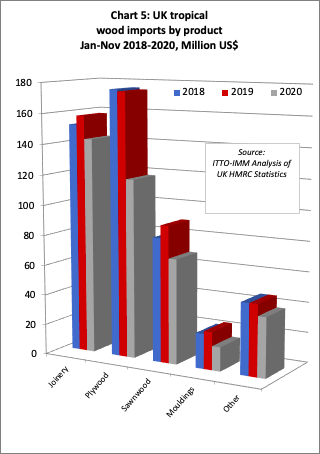

Comparing the first eleven months of 2020 with the same period in 2019, total UK import value of tropical wood products was, at USD386 million, 23% less than the same period in 2019. Import value of joinery products was down 10% at USD143 million, tropical plywood was down 32% at USD118 million, tropical sawnwood fell 23% to USD69 million, and mouldings/decking declined 36% to USD16 million (Chart 5).

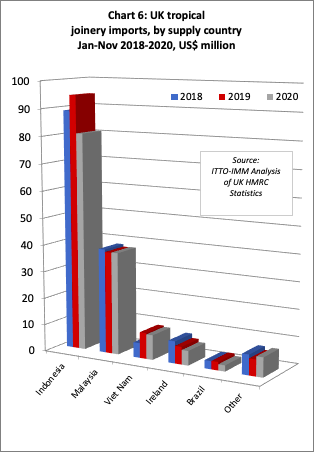

After making gains in 2019, UK imports of tropical joinery products from Indonesia, mainly consisting of doors, fell 15% to USD81 million in the first eleven months of last year (Chart 6). UK imports of wooden doors from Indonesia made up ground between September and November after very low imports between June and August.

After a strong start to the year, UK imports of joinery products from Malaysia and Vietnam (mainly laminated products for kitchen and window applications) stalled almost completely in May before recovering slowly in the summer months and gaining momentum between September and November. Total joinery imports in the first eleven months of 2020 from Malaysia were USD38.0 million, a slight gain from USD37.9 million in the same period in 2019. Imports from Vietnam were USD9.2 million in the first 11 months of last year, 5% less than the same period in 2019.

UK trade in joinery products manufactured from tropical hardwoods in neighbouring Ireland fell dramatically in 2020, down 18% to USD5.4 million in the first eleven months. Imports from Brazil were USD2.3 million, down 27% in the same period.

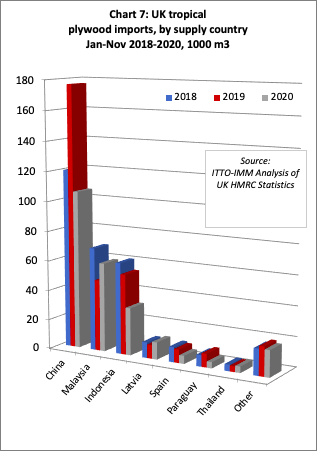

In the first 11 months of 2020, the UK imported 241,000 cu.m of tropical hardwood plywood, 27% less than the same period in 2019. Of this volume, around 44% (106,100 cu.m) comprised tropical hardwood faced plywood from China, 40% less than the same period in 2019 (Chart 7). UK imports of plywood from China ground to halt in the first quarter of last when China went into lockdown. There were hardly any deliveries from February through to early April and UK importers were forced to live off inventories. However imports picked up during the summer months, rising into the autumn with the arrival of significant volumes under delayed contracts.

Likely due to supply problems in China, UK imports of plywood from Malaysia, which were in long term decline before last year, recovered some ground during the pandemic period. Despite significant slowing in May, imports from Malaysia were still up 25% at 59,600 cu.m for the first eleven months of 2020.

In contrast to Malaysian plywood, UK imports of Indonesian plywood fell 41% to 31,900 cu.m in the first eleven months of 2020. In addition to supply problems during the pandemic, Indonesian plywood continues to face intense competitive pressure from birch plywood from Russia, Latvia and Finland.

In recent years, the UK has also been importing a growing volume of tropical hardwood plywood manufactured in Latvia. UK imports of this commodity from Latvia were 11,500 cu.m in the first 11 months of last year, 25% more than the same period in 2019. In contrast, UK imports of tropical hardwood plywood manufactured in Spain fell 40% to 5,400 cu.m in the first 11 months of 2020.

UK tropical sawn hardwood imports make up ground in the second half of 2020

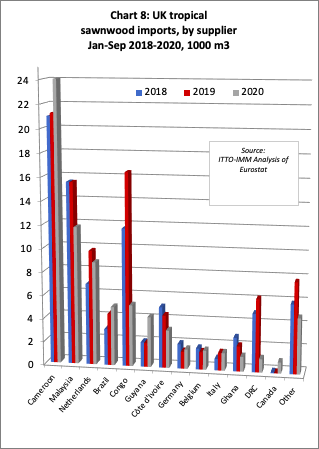

The total quantity of UK imports of tropical sawnwood was 75,300 cu.m in the first 11 months of 2020, 20% less than the same period in 2019. While the UK trade in sawn tropical sawnwood fell sharply in May and June last year, there was some recovery between July and November. By the end of November last year, UK imports were up on the same period in 2019 from Cameroon (+13% to 24,000 cu.m), Brazil (+14% to 5,000 cu.m) and Guyana (+110% to 4300 cu.m).

However imports from all other supply countries were still trailing, with declining imports from Malaysia (-24% to 11,700 cu.m), Republic of Congo (-68% to 5,200 cu.m), Côte d’Ivoire (-28% to 3,200 cu.m), Ghana (-41% to 1,300 cu.m) and DRC (-82% to 1,100 cu.m) (Chart 8).

The UK imported 15,600 cu.m of tropical sawnwood indirectly from EU countries in the first eleven months of 2020, 17% less than in the same period in 2019. Imports fell 10% from the Netherlands to 8,800 cu.m and 50% from Ireland to 400 cu.m. However, imports increased 14% from Germany to 1,700 cu.m and 9% from Belgium to 1,600 cu.m. Imports from Italy were stable at 1,500 cu.m.

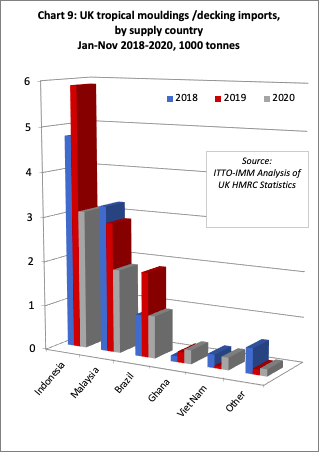

The UK imported 6,700 tonnes of tropical mouldings/decking in the first 11 months of 2020, 40% less than the same period in 2019. Imports were down 47% from Indonesia at 3,100 tonnes, 36% from Malaysia at 1,900 cu.m and 50% from Brazil at 900 cu.m. There was significant growth from Ghana and Vietnam, but from a small base, respectively rising 30% to 300 cu.m and 400% to 300 cu.m. (Chart 9).

PDF of this article:

Copyright ITTO 2021 – All rights reserved