Demand for wood furniture in the EU is rising slowly but the signs are not very positive for external suppliers into the region, particularly from the tropics.

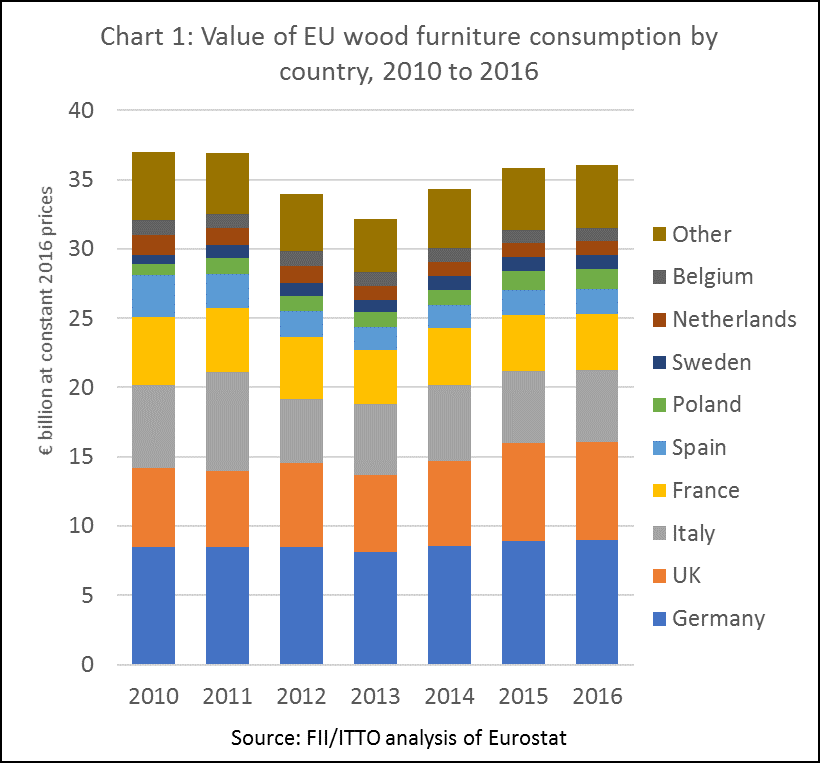

Although the official Eurostat annual production data has yet to be published, a review of Eurostat indices and trade data suggests that EU consumption of wood furniture was around €36.1 billion in 2016, a gain of 1% compared to 2015. During 2016, consumption was quite stable in the largest markets including Germany, the UK, Italy and France compared to the previous year, but consumption increased slightly in Spain, Poland, Sweden and the Netherlands (Chart 1).

The value of EU wood furniture production is estimated to have been around €39.6 billion in 2016, 1% higher than the previous year, but still 20% down on the level prevailing before the financial crises in 2008. A slight slowdown in production in Italy and Germany, the two largest manufacturing countries offset gains in Poland, the UK, Spain, Romania and Lithuania. (Chart 2).

Analysis of Eurostat trade data reveals that internal EU trade in wood furniture was €16.2 billion in 2016, 4% more than the previous year and continuing a rising trend of the previous two years. This trend is driven both by the slow rise in EU consumption and by rising dependence of the internal EU market on manufacturers located in lower cost member states of Eastern Europe, particularly Poland, Romania, and Lithuania.

The EU has maintained a trade surplus in wood furniture since 2011 when exports to non-EU countries overtook imports from outside the EU. However, this surplus has been narrowing, falling from €2.59 billion in 2013 to €1.60 billion in 2016. In 2016, EU exports to non-EU countries fell 4% to €7.31 billion, while imports from non-EU countries fell 1% to €5.71 billion. (Chart 3).

Taken together these trends are indicative of intensifying competition in the EU wood furniture market. EU manufacturers, particularly in Eastern Europe, are producing more at a time when domestic consumption is growing slowly and exports to other parts of the world are weakening.

Last year EU wood furniture exports declined into the Middle East and Russia and were flat into North America, Switzerland, Norway, and Japan. Minor gains in China and a few other emerging markets were insufficient to offset declining demand elsewhere.

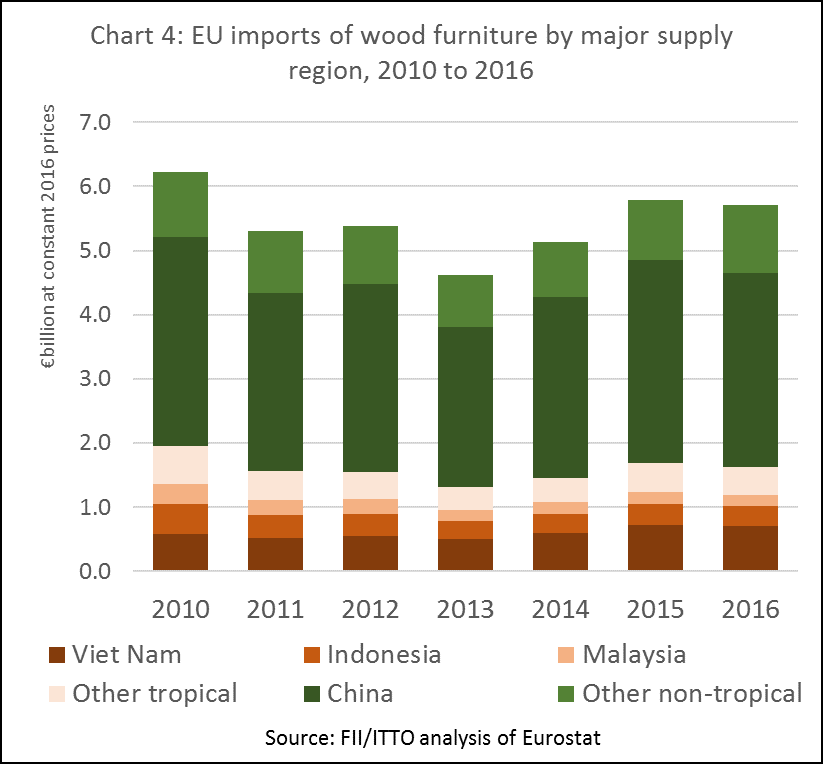

After making significant gains in the EU market in 2015, EU wood furniture imports from China and tropical countries slipped back last year. In 2016, import value declined 5% from China to €3.01 billion and was down 3% from tropical countries to €1.63 billion. However, EU import value from non-EU temperate countries increased by 14% to €1.07 billion, with particularly large gains by Turkey, Bosnia, Serbia, Ukraine and Belarus (Chart 4).

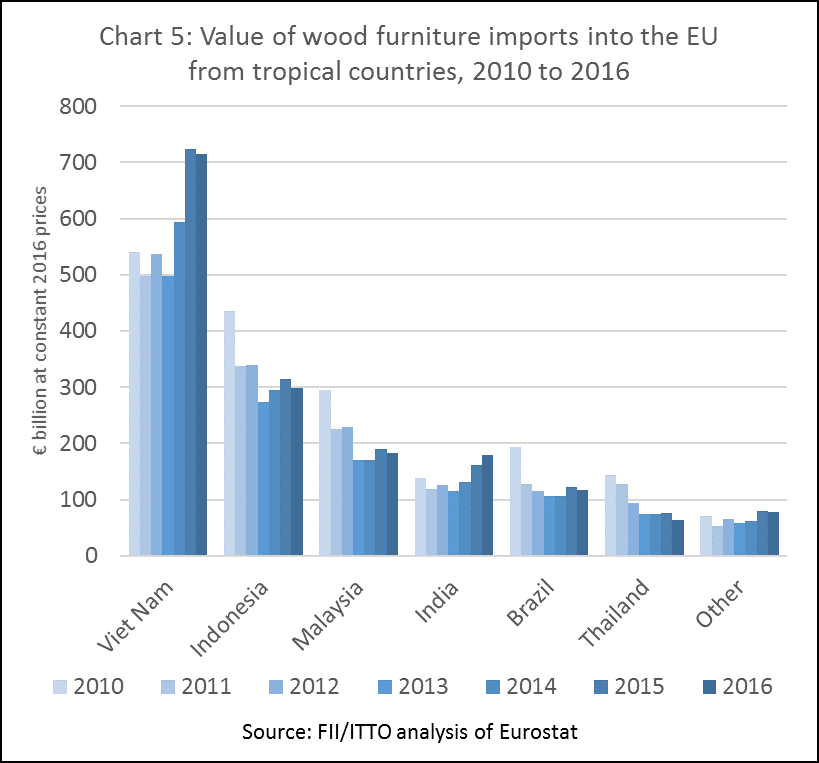

EU import value of wood furniture declined from most of the largest tropical suppliers in 2016. Import value was down 2% from Vietnam to €716 million, 6% from Indonesia to €299 million, 5% from Malaysia to €183 million, 18% from Thailand to €63 million and 3% from Brazil to €118 million. However, India bucked the trend and increased sales in the EU by 10% in 2016, to €179 million (Chart 5).

The total share of tropical countries in EU wood furniture import value remained level at between 28% and 29% in the last four years. However, during this time the share of Vietnam increased at the expense of other South East Asian countries, and also to some extent at the expense of China, although the latter is still dominant. Other temperate supplying countries outside the EU – including Turkey, Serbia, Ukraine and Belarus – have also been increasing share at the expense of China and tropical countries other than Vietnam.

Meanwhile, unlike in North America, the EU’s domestic manufacturers are maintaining their domination of the European wood furniture market. In 2016, domestic manufacturers accounted for around 87% for the total value of wood furniture supplied into the EU market, the same proportion as the previous year and little changed, in fact, since 2007.

There are many reasons for the continuing dominance of domestic manufacturers. An obvious short term factor is weakening of European currencies in the last 2 years – particularly the UK pound – against the dollar and Chinese yuan.

More enduring factors include: the relative high degree of fragmentation in the European retailing sector – which greatly complicates market access for overseas suppliers; the underlying strength of European furniture manufacturers and their brands in terms of innovation and design; the obstacles to overseas suppliers complying with European technical and environmental standards; and the expansion of furniture manufacturing in Eastern Europe, a location which combines ready access to raw materials and to the internal EU market.

Although labour costs are quite high in Europe relative to China and South East Asia, furniture manufacturers in the EU are making a virtue of their shorter supply chains which not only reduce transport costs but also allow products to be delivered and, if necessary, returned more rapidly.

Long-term implications of Brexit for EU wood furniture market

Looking to the future, the UK’s decision to withdraw from the EU, an event scheduled to take place by 2019, has particularly important implications for long-term growth in EU demand for wood furniture from tropical countries, although the precise effects are still far from clear.

The UK’s decision is particularly significant for the wood furniture trade because the UK is not only one of the largest consuming markets in the EU, but is relatively highly dependent on imports.

As much as 45% of all wood furniture purchased in the UK in 2016 was imported, more than in any other large European consuming market including Italy (8%), Spain (26%) and Germany (40%). A relatively high proportion of the wood furniture imported into the UK is from countries outside the EU. The UK accounted for more 34% of all wood furniture, and 40% of tropical wood furniture, imported by the EU from outside the region in 2016.

The immediate impact of the Brexit vote was to increase the rate of depreciation of the British pound on foreign exchange markets. The pound fell 15% against the US dollar and 10% against the euro in the immediate aftermath of the vote, and the value has remained at the lower level ever since.

The effects of the Brexit vote and weak pound have taken time to filter through into the British furniture market place. The British Retail Consortium (BRC) reported no discernible impact on retail spending and shop prices in the second half of 2016.

However, the higher prices for imported goods combined with uncertainty about long-term economic effects of Brexit now appear to be discouraging consumer spending. According to a study from Deloitte LLP, U.K. consumer confidence weakened in the first quarter of 2017 and households were the most pessimistic about their finances in more than two years.

Longer-term, U.K. market prospects for wood furniture exporters in tropical countries will be significantly impacted by the outcome of negotiations on the terms of the withdrawal from the EU.

In the event of a so-called “soft Brexit” in which the U.K. remains a part of the EU single market, there may not be a significant change in the current trading environment.

However, this will require both parties to compromise on what, at present, are polarised positions on difficult political issues such as the size of the U.K.’s on-going contribution to the EU budget and the free movement of labour within the single market.

If there is a so-called “hard Brexit” in which the UK fails to reach agreement with the rest of the EU and withdraws or is ejected from the single market – an event which could occur in 2019 – there is very likely to be severe economic fallout in the UK and, to some extent, other EU countries.

Unlike the Brexit vote – which didn’t actually lead to any change in the terms of the trading relationship – the U.K.’s withdrawal from the single market would have immediate and very profound effects.

It would impact on investment decisions, consumer spending and confidence, and on immigration and the level of access to, and the price of, labour. The UK’s pre-eminent position in the EU in several large service sectors – such as finance and pharmaceuticals – would come under threat with far-reaching implications for the long-term health of the national economy.

A “hard Brexit” would also lead to immediate imposition of tariffs on goods from the EU that previously entered the country tax free. There would be very profound economic dislocation in those sectors that have progressed furthest to integrate supply chains between the EU and UK, such as car manufacturing, electrical goods and chemicals.

There would also be far-reaching effects on those sectors – such building materials and children’s toys – where technical and safety standards have been harmonised across the EU.

In these sectors, if the U.K. leaves the single market without, at minimum, mutual recognition with EU conformity assessment bodies, trade would be severely curtailed until the required agreements are put in place. Given the number and complexity of sectors involved, that would take some time.

It should be said that the wood furniture importing sector in the UK is relatively less exposed to this form of dislocation compared to other industries. EU import tariffs are already zero on all wood furniture with the exception of components and kitchen furniture which are subject to 2.7% tariff.

The furniture sector is also a so-called “non-harmonised sector” in EU trade law. This means goods are not subject to common EU rules and instead come under national rules. The sector is regulated through the so-called “mutual recognition principle” which states that a Member State must allow a product lawfully produced and marketed in another Member State into its own market.

This is true even if the importing Member State’s local rules impose more stringent (or different) requirements to which the product does not conform.

The importing Member State can disregard this principle only under strictly defined circumstances, such as where public health, the environment or consumer safety are at risk, and where the measures taken can be shown to be proportionate.

In the U.K., there are national requirements for fire safety in furniture which are mandatory for all products placed on the market, irrespective of whether from the EU or outside the EU. Imported furniture must be accompanied by documented proof of compliance and with the required permanent labels attached.

What this means in practice is that the U.K.’s withdrawal from the single market may not significantly alter the terms of trade for wood furniture imported into the country – since there is already a fairly level playing field between U.K. imports from inside and outside the EU.

Nevertheless, the U.K.’s departure from the free market would mean, at minimum, restrictions on the current free movement of EU goods into the country. A customs clearance process would be imposed for goods coming into the UK from the EU, and vice versa. Each furniture product would need a customer code and be subject to scrutiny by customs at the border.

This adds a layer of trading complexity and increases the potential for delayed shipments, a critical issue in the furniture sector.

The large furniture retailers in the U.K. that already import a lot of product from outside the EU are geared up for this and may benefit from the U.K. leaving the single market.

In contrast, smaller U.K. retailers, and others that are heavily dependent on imports from the EU, might be at a competitive disadvantage. Large pan-European retailers like Kingfisher and IKEA that operate a centralised sourcing strategy and have gone a considerable way to integrate their distribution networks and harmonise sales activities across the continent would have to alter their business model in the U.K.

IKEA, which currently sources the majority of its wood furniture from mainland Europe, is sufficiently concerned about the prospect of the U.K. leaving the single market that it recently announced its’ intention to manufacture more furniture in the U.K. According to IKEA, this will help fend-off Brexit-led price rises and competition from outside the EU. The company has stated that it aims to double market share in the UK irrespective of the outcome of Brexit negotiations.

Overall, it seems that the U.K.’s departure from the EU might provide some new opportunities for suppliers of wood furniture in tropical countries into the country. However, it would be wrong to overstate the potential.

A “hard Brexit”, although a distinct possibility, is not certain and there are powerful commercial voices on both sides still lobbying hard for the U.K. to remain a part of the single market.

Even if the U.K. leaves the EU single market, the U.K. domestic furniture industry, and large European manufacturers like IKEA, are already developing strategies to steer off what they perceive to be a renewed challenge from competitors outside the EU.

If new opportunities are to emerge for tropical wood furniture suppliers in the U.K. post-Brexit, they will need to work closely with the large retailing chains – both the high-street stores and e-retailers – that already have global supply chains and will be most willing to make savings and offer lower prices by expanding procurement in tropical countries.

There may also be opportunities at the lower-volume, high end of the market for good quality designer products from the tropics, if these can be shown to be supported by a strong social and environmental narrative. However, that requires significant investment in both design and marketing.

PDF of this article:

Copyright ITTO 2020 – All rights reserved