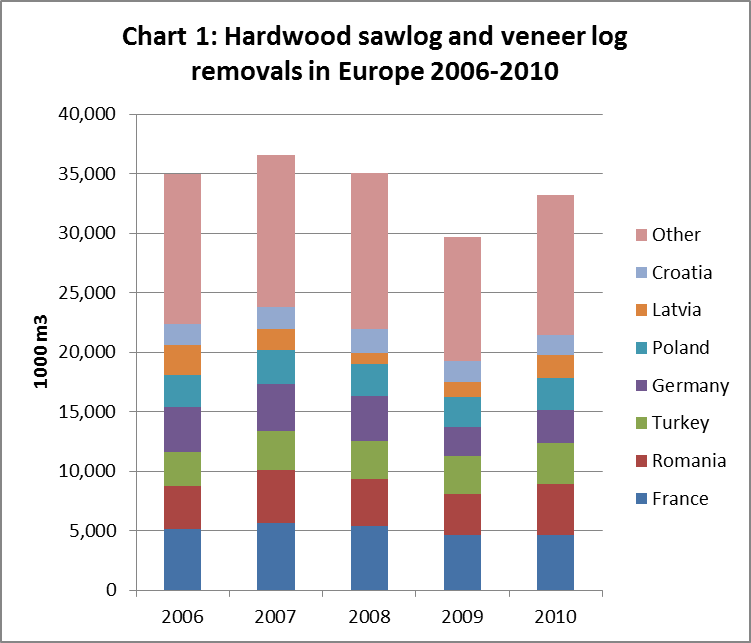

Data from the UNECE Timber Committee indicates that hardwood production across the European subregion rebounded during 2010 (the UNECE European subregion includes all countries within the continent of Europe plus Turkey but excluding Russia). Following an 18% decline in hardwood saw and veneer log production in the region between 2007 and 2009 to 29.7 million m3, production rebounded by 12% to 33.2 million m3 in 2010 (Chart 1). Significant increases in hardwood log production were recorded in Romania, Germany, Turkey, and Latvia during 2010. 26.2 million m3 (78%) of total European hardwood log production during 2010 was in EU countries.

Source: UNECE Timber Committee

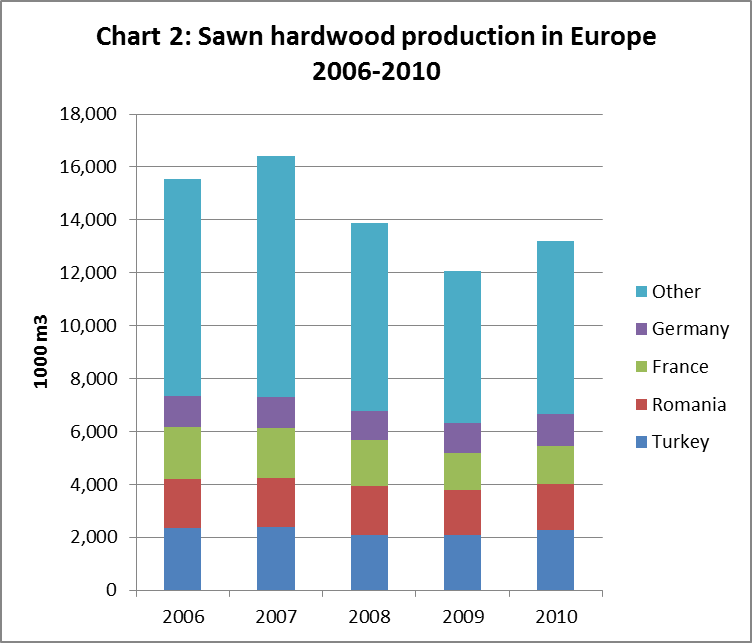

European production of sawn hardwood followed the same general trend. A 26% fall in production between 2007 and 2009 was followed by a robust 9% rebound during 2010 (Chart 2). Significant gains in production were in Turkey (8.8%), Germany (6.6%) and Croatia (5.6%).

Source: UNECE Timber Committee

Turkey was the largest producer of sawn hardwood in Europe in 2010. However most sawn hardwood in Turkey is produced from low-grade domestic timber, as well as small-dimension plantation logs and is destined for the pallet and packaging industry with only a small proportion earmarked for export. Germany, France and Romania remain by far the dominant producers of higher grades of European sawn hardwood.

The rising log harvest in 2010 combined with an underlying lack of consumption has meant that there have been no major hardwood log shortages in Europe in recent times. Supplies of beech logs have generally been adequate. Short-term concerns have occasionally arisen over supplies of oak logs, particularly with rising demand in export markets, notably from China, and following severe winter weather in both 2009 and 2010 which briefly curtailed harvesting levels. However oak log supply problems had eased greatly by the end of the first quarter of 2011 as weather conditions improved and log exporters were less active at French and German auction sales.

European domestic producers become more dominant

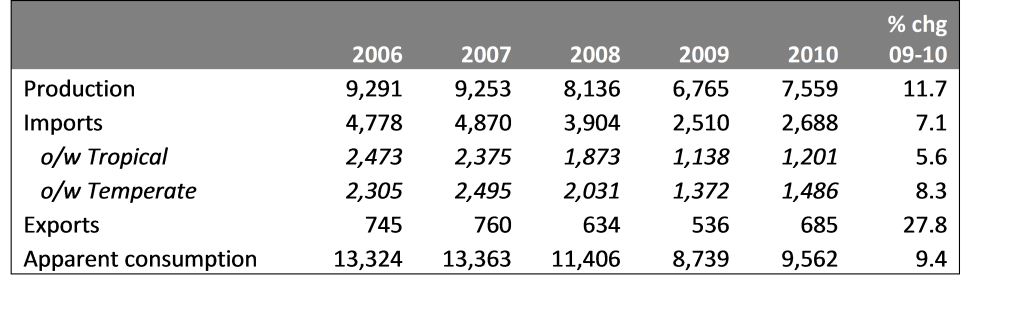

Within the EU-25 group of countries, apparent consumption of sawn hardwood increased by 9.4% during 2010, from 8.7 to 9.6 million m3 (Table 1). While a significant gain, consumption levels were still well down on levels of over 13 million m3 which prevailed prior to the economic crises. The overall figure also hides important changes in sources of supply and demand.

Table 1: EU-25 sawn hardwood balance 2006-2010 (1000 m3)

Source: Production data derived from UNECE Timber Committee, import and export data from Forest Industries Intelligence Ltd and BTS Ltd

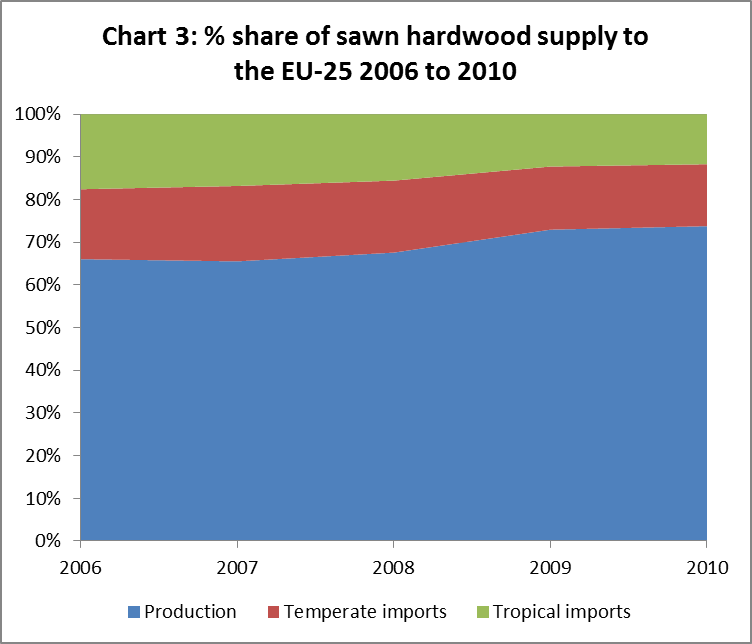

While all wood suppliers into the EU market suffered severely during the recession, the signs are that the domestic industry weathered the storm better than most external suppliers. During the period 2006 to 2010, the share of domestic hardwood sawn lumber in overall supply to the EU-25 group of countries increased from 66% to 74% (Chart 3). Meanwhile the share of non-EU temperate hardwood suppliers declined from 16% to 15%. However the major loser in this process has been tropical hardwood which saw share of European sawn hardwood supply fall from 18% to 12% in the four year period. While all major tropical supply countries experienced some slippage in European market share for sawn hardwood, the trend was particularly pronounced for Brazil (share of EU supply falling from 4.1% to 2.9%) Ivory Coast (share falling from 2% to 1%), and Ghana (share falling from 0.8% to 0.4%).

A number of factors have played a role in this major shift in European sawn hardwood supply including:

- increased diversion of global hardwood supply away from Europe to China and emerging markets;

- a move to smaller stock-holdings and just-in-time ordering during the credit crunch which has tended to favour more readily available products with shorter lead times;

- the willingness of European domestic suppliers to deliver to the precise specifications of European manufacturers;

- the willingness of the European state forest sector to continue to harvest hardwood logs during the recession despite relatively low log prices;

- the continuing strong fashion for European oak in the region;

- the development of an expanding range of treatment techniques allowing use of European hardwoods for a much wider range of looks and applications;

- and environmental concerns which have benefited FSC and PEFC certified hardwoods, the majority of which derive from Europe.

On the demand side, European consumption of sawn hardwood recovered quite strongly in France, Germany, and Sweden during 2010 and early 2011. However consumption has remained at historically low levels in many European markets, notably Spain, Portugal, and Italy due to continuing low demand in the cabinet, furniture and parquet industries. The strong euro has meant that Europe’s important furniture sector is coming under particularly intense pressure from competitors in Asia.

Export markets for European sawn hardwood, particularly oak and ash, in China and Vietnam have also been recovering. Between 2009 and 2010, EU-25 sawn hardwood exports to China increased from 115,000 m3 to 205,000 m3, while exports to Vietnam increased from 21,000 m3 to 40,000 m3. In contrast, European sawn hardwood exports to the Middle East and North Africa have been declining. Recent political upheaval in this region has resulted in declining demand, particularly for beech in Egypt, Jordan, Syria, and Tunisia.

Despite pockets of poor demand, according to the UNECE Timber Committee, reports from the European hardwood sawmilling sector have been generally positive in 2011 and there are expectations that overall sales this year may be 15% to 20% higher than in 2010.

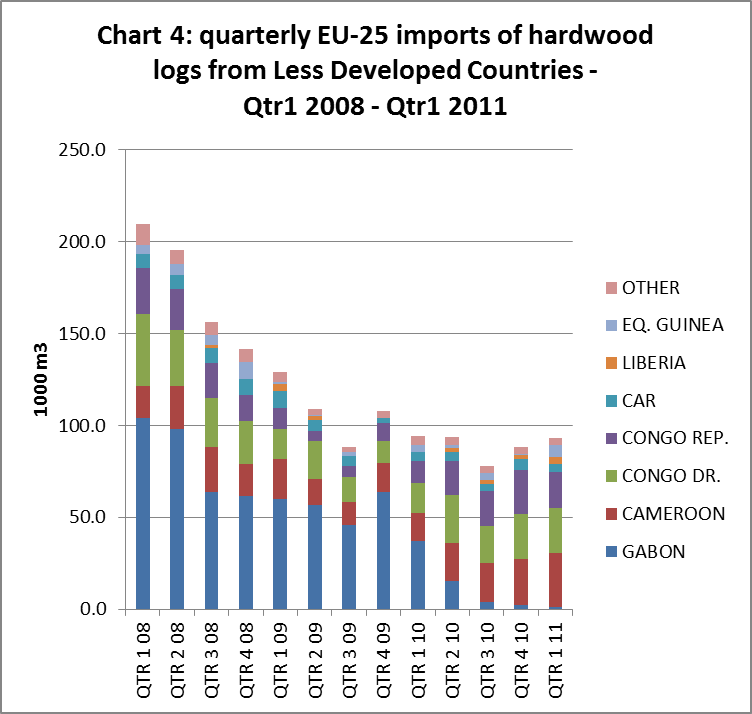

European tropical hardwood log imports low but stable

The EU-25 imported 93,400 m3 of tropical hardwood logs during the first quarter of 2011, a 6% increase on the previous quarter, but 1% down on the same quarter in 2010 (Chart 4). Following the dramatic decline in imports from over 200,000 m3 in the first quarter of 2008 to a low of 88,000 m3 in the third quarter of 2009, quarterly imports have stabilised at this lower level. In addition to the recession, a major factor driving the recent decline in log imports was Gabon’s imposition of a log export ban from May 2010 onwards. Rising log imports from Cameroon, Democratic Republic of Congo, Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea and Liberia have only partially offset the decline in availability from Gabon.

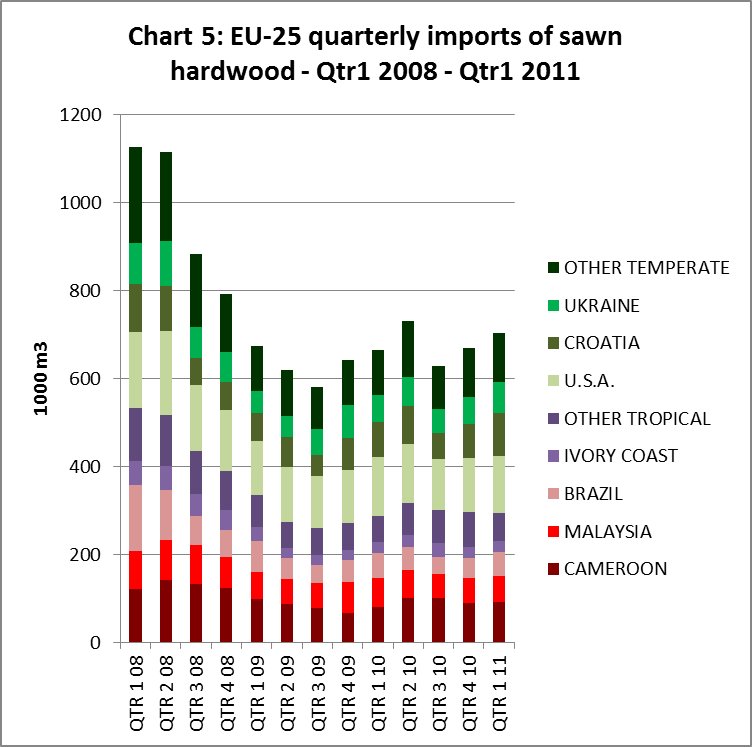

Rise in EU hardwood imports driven by temperate species

The EU-25 imported 702,000 m3 of sawn hardwood during the first quarter of 2011, a 5% increase on the previous quarter and a 6% increase on the same quarter in 2010 (Chart 5). However tropical sawn hardwood imports of 293,000 m3 during the first quarter of 2011 were 1% down on the previous quarter and only 2% up on the same quarter in 2010. This compares to temperate hardwood sawn imports of 409,000 m3 during the first quarter of 2011, up 10% on the previous quarter and up 9% on the same quarter in 2011. Most recent gains in EU-25 imports of temperate hardwoods have been made by Croatia and Ukraine. Recent news is not all bad for tropical hardwoods. Brazilian sawn hardwood has been regaining some of the ground lost in the European market, particularly in France and Belgium. In the first quarter of 2011, EU-25 imports of sawn hardwood from Brazil were 56,000 m3, up 22% on the previous quarter. Meanwhile European imports from Cameroon started 2011 much more strongly than the previous year, with larger volumes arriving in Belgium, Netherlands, UK, Ireland and Italy. Total EU-25 imports of sawn hardwood from Cameroon reached 92,000 m3 in the first 3 months of 2011, up 14% on the same period in 2010. These gains helped offset relatively weak first quarter imports of sawn hardwood from Malaysia (58,000 m3) and Ivory Coast (24,000 m3).

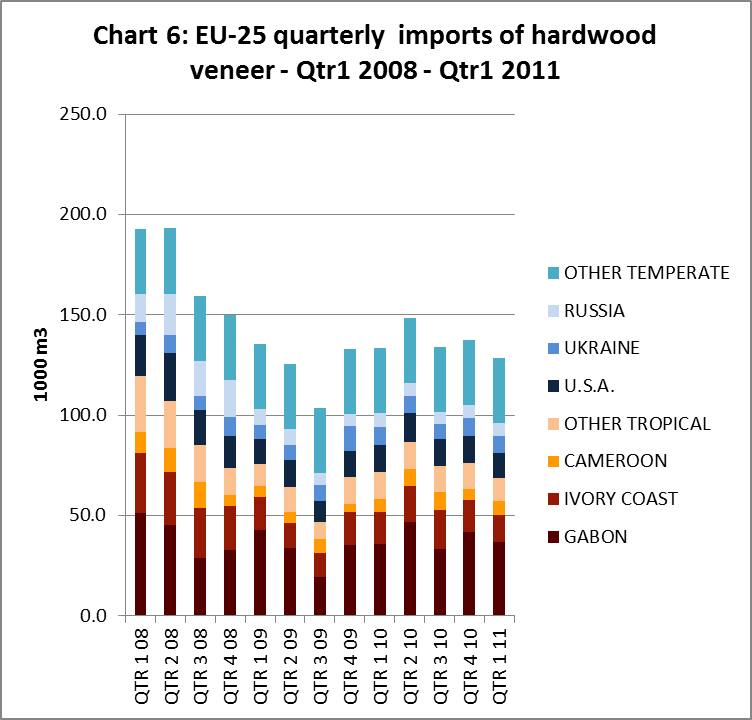

EU hardwood veneer imports weaken again

The EU-25 imported 118,000 m3 of hardwood veneer during the first quarter of 2011, an 8% decline on the previous quarter and a 4% decline on the same quarter in 2010 (Chart 6). Tropical hardwood veneer imports of 69,000 m3 during the first quarter of 2011 were 10% down on the previous quarter and 4% down on the same quarter in 2010. This compares to temperate hardwood veneer imports of 60,000 m3 during the first quarter of 2011, down 2% on the previous quarter and 3% on the same quarter in 2011.

The continuing weakness of the European veneer trade is particularly troubling considering the wide range of end-use sectors for hardwood veneers, the resources committed to boosting the share of real wood by large veneer manufacturers, and the decline in Europe’s tropical hardwood log imports.

European plywood manufacturers might reasonably have been expected to have offset the decline in availability of okoume logs by importing more rotary veneer from Gabon. However European imports of this commodity have remained low as manufacturers have been struggling in the face of tight margins and rising competition from a range of lower-priced panels. European imports of thicker rotary veneer for flooring are also depressed as European flooring output is low due to weak construction growth and competition from artificial surfaces.

The weak construction sector has also hit mainstream markets for sliced veneer, including doors, panels and furniture. The latter sector is struggling in the face of stiff competition from Chinese manufacturers. At the same time, real wood veneer has continued to lose out to artificial surfaces. As demand for sliced veneer has been increasingly marginalised in mainstream markets, demand is now focusing more on higher value niche markets -including high end interior fittings, yachts, and the car industry – which generate more value but absorb lower volumes.

Changes to the CE marking regime

Significant changes are underway in the CE Marking regime with potential to impact on the European trade in tropical timbers. The European Commission recently decided to end early the so-called “co-existence period” for strength graded structural timber and require mandatory CE-marking of these products from 1 January 2012. The EC had previously indicated that this requirement would only be imposed from 1 September 2012.

In a separate development, from July 2013 CE Marking will become mandatory in the supply of all eligible construction products in the four EU countries – the UK, Republic of Ireland, Finland, and Sweden – which, since 1989, have opted out of mandatory imposition of CE Marking under the Construction Products Directive (CPD). The change will happen when the CPD is replaced by the new Construction Products Regulations (CPR).

On coming into force in July 2013, the new CPR will also impose additional environmental standards on construction products. The CPR states that construction products should not “exert an exceedingly high impact over their entire life cycle to the environmental quality nor to the climate” and there should “be sustainable use of natural resources”. In the future, manufacturers and assessment bodies will be obliged to consider whether construction works and materials make sustainable use of natural resources.

CE Marking applies to construction products sold in the EU to ensure they meet safety, environmental protection, health and consumer protection standards required by the CPD. CE-Marking is applicable to construction products covered by a European Norm (EN). On publication of a new EN standard, the European Commission will also publish the date at which EU manufacturers may begin to apply CE marking to the product concerned – usually nine months after the date of availability of the standard. After this date the “coexistence period” begins (usually 12 months), during which manufacturers are free to use the new EN and apply CE marking, or continue to use the old national standards without CE marking. After the period of coexistence, conflicting national standards must be withdrawn (except, until 2013, in those EU Member States that have opted out) and all products must comply with the harmonised EN standard.

Wood-based construction products currently covered by harmonised EN standards include: strength-graded structural timber; wood-based panels; solid wood panelling and cladding wood flooring products; glulam; prefabricated structural members and wall, floor and roof elements; structural LVL; and impregnated and finger-jointed structural timber.

The exact procedures (the so-called Attestation of Conformance or “AoC” level) to demonstrate conformance to different EN standards varies. In most instances it will require the services of a “European Notified Body” which is a third-party recognised as competent to carry out the conformity assessment tasks laid down in the standard.

Further information on CPD European Notified Bodies may be obtained from: http://www.gnb-cpd.eu/index.jsp.

The list of notified bodies can be searched at: http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/newapproach/nando/index.cfm?fuseaction=search.main.

Further details of recent and anticipated changes to the CE Marking regime are available in a new briefing prepared by TRADA:

http://www.trada.co.uk/downloads/constructionBriefings/European%20CPR.pdf

EU Timber Regulation

A series of consultations have been held in recent months on “implementing regulations” for the EU Timber Regulation (EUTR) which from March 2013 will impose a prohibition on trade in wood from any illegal source and a requirement for importers to implement due diligence systems. The regulations will establish more detailed requirements for the risk assessment and mitigation procedures that must be implemented by importers from March 2013. They will also establish rules for so-called “Monitoring Organisations”, a concept introduced into the EUTR as a mechanism to reduce costs of compliance for smaller European importers and producers. The final report and recommendations from this series of consultations prepared by the European Forestry Institute (EFI) is published at http://ec.europa.eu/environment/forests/pdf/EUTR-Final_Report.pdf.

A central concern during consultations was the extent to which it should be necessary to trace timber to forest of origin in order to demonstrate a negligible risk of illegality. In their publicity material, the European Commission has tended to emphasise the role of the legislation in increasing traceability of wood products to source. However, discussions at consultation meetings highlighted the complexity of the supply chains that EU operators must deal with and showed that identification of the forest of origin would be an impossible task in anything other than the shortest and simplest of supply chains.

Furthermore, a close reading of the legislative text reveals that operators are actually under no obligation to identify the precise forest of origin of timber for each parcel of timber. Rather they are required, through their due diligence systems, to ensure that timber origin can be identified to the extent necessary to make a reliable assessment of negligible risk. In some cases this might require identification of source only as far as a low risk country of origin.

The EFI report considers the considerable progress being made to develop and expand third party verification and forest certification systems, which when available will provide an effective risk mitigation tool. However the report also cautions against over-reliance on these mechanisms noting that “only around 10% of the world’s forests are certified to date, and mostly outside of the tropics. Therefore the current global needs for wood cannot be fulfilled purely from certified forests. Moreover, due to the lengthy certification process, the associated costs, and the limited amount of licensed certifiers, this mitigation option has its restrictions as a quick and extensive mitigation response at a global scale.”

A key issue identified in the EFI report is that lack of awareness of EUTR amongst smaller companies is likely to be a major obstacle to implementation. The report notes that “very few” SMEs in Europe have ever even heard of the EUTR and that “even membership in a well represented association or federation does not mean that information [on EUTR] will reach them”.

In the light of these concerns, the EFI report steers clear of proposing any far-reaching additional traceability, documentation or certification requirements on timber traders. The report notes that: “It is evident that any possible outcome of the implementation regulation must acknowledge the variety of affected actors across the different industry sectors. For example, SMEs have fewer resources to spend for verifying legality than the big corporations have. Therefore, the operators should define their respective DDSs [Due Diligence Systems] and include the most suitable tool set for their implementation. Due to the high degree of different conditions, it is not feasible to develop a fixed and uniform DDS description which would be applicable for all operators”.

Proposals for specific documentation to be demanded of overseas suppliers by European importers are limited to “a signed commitment ….from the supplier side to deliver legal wood or wood based products to the operator” and a “signed legal document” which would be a “written contract signed between the parties of the transaction” to include information such as “type and description of the product, species (either a common name or scientific name), volume, country of harvest and contact details of the parties.” It is acknowledged that these documents “will not serve as a proof for legality” but will only provide an assurance of the suppliers’ policy to avoid illegal wood.

EFI also propose that “depending on the country of origin and the related risk level, the buyer may ask for more detailed information on the origin of the timber on a regional, sub-regional or stand level” and propose that this information be gathered through a standard “information collection form”.

However the EFI report acknowledges that many individual operators, particularly SMEs, will not have time, resources or expertise to undertake reliable assessment of information collected in these standard forms. There will be a need to develop frameworks for outsourcing of risk assessment to independent experts better qualified to assess risk and drawing on more detailed and relevant indicators. This may involve the establishment of centralised independent databases categorising levels of risk for regions or suppliers.

The EFI report also includes recommendations for Monitoring Organisations (MO). These form a key part of the European Commission’s strategy to overcome the challenges presented by industry fragmentation. Rather than having to develop their own due diligence systems, the EUTR gives European operators the option of participating in a group due diligence system managed by an MO.

The original assumption was that European trade associations and NGOs that are already operating green procurement codes and systems for member companies would apply to act as MOs. The role of MOs would be similar to that of organisations like forestry associations or consultancies that organise and act on behalf of groups of smaller forest owners to facilitate their participation in FSC or PEFC group certification. The regulatory authorities would benefit because the private sector would be engaged as active partners in the regulatory process. Members would benefit from lower unit costs of compliance. The MOs would benefit through expanded membership.

However, rather than seeing MOs as facilitating bodies, EFI’s recommendations assume that MOs should act more like conformity assessment bodies. As such, EFI proposes that they should conform to a complex set of ISO procedures and standards for such bodies. Requiring MOs to implement such standards might be costly and make compliance difficult for many organisations that had been hoping to act as MOs – notably timber importing associations. It remains to be seen how this issue will be resolved.

FLEGT VPA Process gathers pace

An underlying assumption of the EUTR is that the majority of tropical timber imported into the EU in the future will be covered by legality verification systems established as part of FLEGT Voluntary Partnership Agreements (VPAs). The EUTR states that FLEGT VPA licensed timber will be considered to have been legally harvested and therefore need not be subject to any further risk mitigation action by EU operators. Suppliers in countries that are signatories to a FLEGT VPA with the EU therefore need not fear any discrimination as a result of the legislation and may have a competitive edge over suppliers in non-VPA countries.

Recent reports from the FLEGT Unit at the European Forestry Institute indicate that the VPA process has been widening its range and gathering pace in recent months. No country has yet reached the “full implementation and licensing phase” when each timber product shipped from the partner country to the EU will have to be accompanied by a FLEGT license before being given access to the EU market.

However, there are now 6 countries in the “VPA system development phase”: Cameroon, Central African Republic, Ghana, Indonesia, Liberia, and Republic of Congo. During this phase, VPA partners develop systems and any new capacity required to control, verify and license legal timber in line with VPA requirements. The system development phase will only be concluded following an evaluation demonstrating that the “Legality Assurance System” (LAS) is fully operational.

An additional four countries are at the “VPA negotiation phase” and have yet to sign formal VPA agreements: Democratic Republic of Congo, Gabon, Malaysia, and Vietnam. Various other countries have not yet entered formal VPA negotiations but have requested and are being provided with more information. These countries include: in Central and South America – Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, and Peru; in Asia Pacific – Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and Thailand; and in Africa – Côte d’Ivoire and Sierra Leone.

PDF of this article:

Copyright ITTO 2020 – All rights reserved