Indonesia issued the first ever FLEGT licenses in mid-November last year with high expectations that these would boost the value and share of Indonesia’s wood exports to the EU. This is a reasonable expectation, given the very significant commitment and investment by Indonesia, supported through the FLEGT Voluntary Partnership Agreement with the EU, and the mandatory requirement that all timber and timber products exported from Indonesia to the EU must now be licensed.

The fact that EU importers no longer need to undertake a potentially expensive due diligence assessment to demonstrate EUTR conformance for any timber product of Indonesian origin should give a significant edge in the EU’s highly competitive market.

Nor has Indonesia stopped short at imposing a requirement for exports to the EU. The SVLK certification system on which FLEGT licensing is based (and which was first introduced in 2010) is now mandatory for nearly all wood produced and traded in the country and applies to industrial plantations (HTI), natural forest concessions (HPH) and community plantation forests (HTR).

Anecdotal evidence indicates that Indonesia’s SVLK certificates and FLEGT licenses have been well received and are at least benefitting some Indonesian suppliers. For example, the Jakarta Post reported on 17 March that “many exhibitors at the recent Indonesian International Furniture Exhibition (IFEX) said the SVLK helped them increase exports, especially to the EU”.

The news report quotes one Indonesian furniture exporter as suggesting that “with the SVLK, buyers from the EU are more confident about us and we can even sell directly to them without using traders, and so we enjoy high profit margins and a market under our own brand”. The increase in profit margin in this instance was reported to be up to 40% compared to 10% previously.

There is similar anecdotal evidence from European importers. In an interview published on the Global Timber Forum website in February this year, a representative of one of Europe’s largest importers of Indonesian plywood said that “arrivals from Indonesia have increased over the last few weeks as importers and traders are stocking up on FLEGT licensed material”.

He noted that the FLEGT license has given European importers more confidence to engage in active promotion to increase sales of Indonesian plywood and to make more product available in the market. He added that Indonesia will have an increasing advantage over time as EU Competent Authorities are getting stricter and there are more checks on operators.

These early anecdotal reports are encouraging, but they refer to isolated cases and the underlying question of the extent to which FLEGT licensing contributes to real increases in export share and value remains uncertain.

Relaunch of IMM programme to monitor impact of FLEGT licensing

This is a question which will be a key focus of the FLEGT Independent Market Monitoring (IMM) programme which prepared baseline market research during the period March 2014 to 2016, and which was relaunched on 1 April 2017. IMM is a multi-year project supervised by ITTO and financed by the EU to support implementation of VPAs between the EU and timber supplying countries.

The task of assessing the impact of FLEGT Licensing on Indonesian trade with the EU and other markets is complicated by the changing profile of timber product exports from Indonesia.

In Europe, the trade has traditionally viewed Indonesia primarily as a source of tropical hardwood plywood and decking. While these products are still significant, Indonesia has evolved a very diverse wood manufacturing sector and supplies the EU with increasingly wide range of more added value wood products such as furniture, doors and other joinery.

In 2016, the value of EU imports of joinery products from Indonesia was close to €75 million and wood furniture around €300 million. This compares to EU imports of around €70 million of decking and other mouldings and €75 million of plywood from Indonesia.

Last year the EU also imported pulp and paper products from Indonesia with a total value of €225 million. Although this is only a very small proportion of both EU and Indonesian trade in pulp and paper, the industry is so large that this value is comparable to that of wood products.

If all these products are considered and Brazil is excluded (since most Brazilian wood product exports now derive from outside the tropical region), Indonesia is the largest tropical supplier of forest products to the EU by a significant margin.

Total EU forest product imports from Indonesia were just over €1 billion in 2016, up 3% on the previous year. This compares to EU imports of €816 million from Vietnam and €550 million from Malaysia (both of which unlike Indonesia exported less to the EU in 2016). Last year Indonesia accounted for 24.4% of EU imports of timber and timber products from the tropics (by value), up from 23.8% the previous year.

Changing profile of Indonesia’s wood product supply

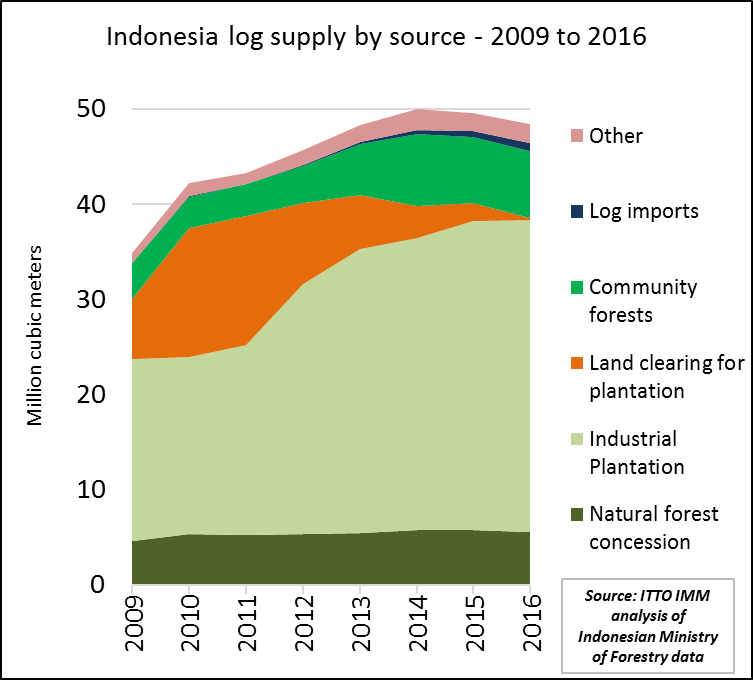

The changing profile of Indonesia in product supply is closely tied to the changing structure of the resource. This is evident from data published by the Indonesian Ministry of Forestry on the source of log supply which shows that industrial plantations are becoming increasingly important while the share of supply from natural forests is falling. Production from sustainably managed concessions in natural forest is now stable, but there has been a sharp decline in forest conversion operations (Chart 1).

Last year Indonesia produced 47.5 million m3 of logs of which 69% derived from industrial plantations (HTI), 15% from community forests (HTR), 12% from natural forest concessions (HPH), less than 1% from land clearing, and 4% from a variety of other sources. This compares to 2009 when log production was 34.8 million m3 of which 55% was from industrial plantations (HTI), 11% from community forests (HTR), 13% from natural forest concessions (HPH), 18% from land clearing operations, and 3% from a variety of other sources.

Another complexity in monitoring market impacts of FLEGT licensing is that the EU only takes a relatively small share of Indonesia’s total timber product exports. The priority attached to the EU in market development, and the size of flows to the EU, are therefore heavily dependent on events in other parts of the world.

Data from the Environment and Forestry Ministry show that total forest product exports through Indonesia’s legality licensing system were 17.46 million tons with a value of USD9.27 billion in 2016. Of these exports the EU accounted for only 4.7% of tonnage and 9.4% of value. The large majority of Indonesian forest product exports are destined for other Asian markets (86% of tonnage and 71% of value) while exports to North America are also significant (4.3% of tonnage and 10.7%) of value.

While the EU has a low share of Indonesia’s total forest product exports, the data is influenced by the small proportion of Indonesian pulp and paper destined for the EU. In the EU, Indonesia faces very stiff competition from Brazil in the market for chemical pulp (which derives from fast-growing plantations of eucalyptus and other hardwood species) and from domestic European producers in supply of finished paper products. The large majority of Indonesia’s pulp and paper product exports are destined for China and other Asian markets.

The EU is relatively more important in Indonesian exports of some wood products, most notably furniture. Of Indonesia’s total wood furniture exports of 435,000 tonnes with a value of USD1.34 billion in 2015, 127,000 tonnes (29%) with a value of USD319 million (24%) were destined for the EU.

A preliminary review of prospects for Indonesian wood products in the EU market due to FLEGT licensing was provided in a previous ITTO MIS report (16-30 Sept 2017). This suggested that FLEGT licensing offers an immediate opportunity for Indonesian suppliers to retake share in those sectors – such as decking, plywood and flooring – where Indonesian products are familiar to EU importers and already favoured for their strong technical performance, but where demand has been dampened by concerns over the legality of wood supply.

It also suggested that, in isolation, FLEGT licensing is less likely to generate immediate benefits in those high value sectors like furniture and joinery where the specific technical and environmental features of Indonesian wood products have been less significant barriers to competitiveness than wider issues such as labour costs, red tape, logistics, processing efficiency, innovation, and marketing.

In these sectors, increasing share is only likely to be achieved if FLEGT licensing is combined with market development initiatives to improve the international competitiveness of Indonesian wood manufacturers across a wider range of issues. However, the long-term benefits of investment in these initiatives, alongside FLEGT licensing, would be considerable given the sheer size of markets for consumer products like furniture, the relatively high proportion of Indonesian furniture exports already destined for the EU, and the greater potential to add value to wood fibre.

Near real-time monitoring of FLEGT licensed trade

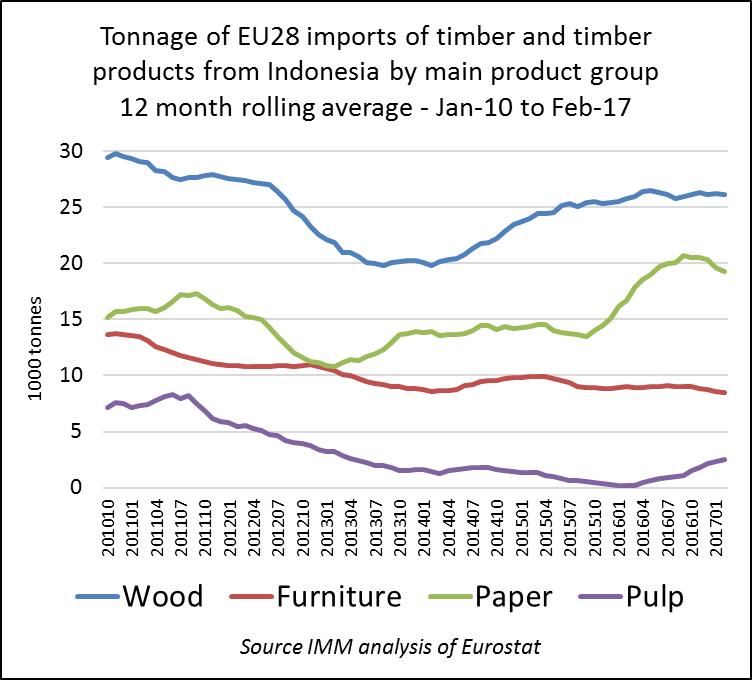

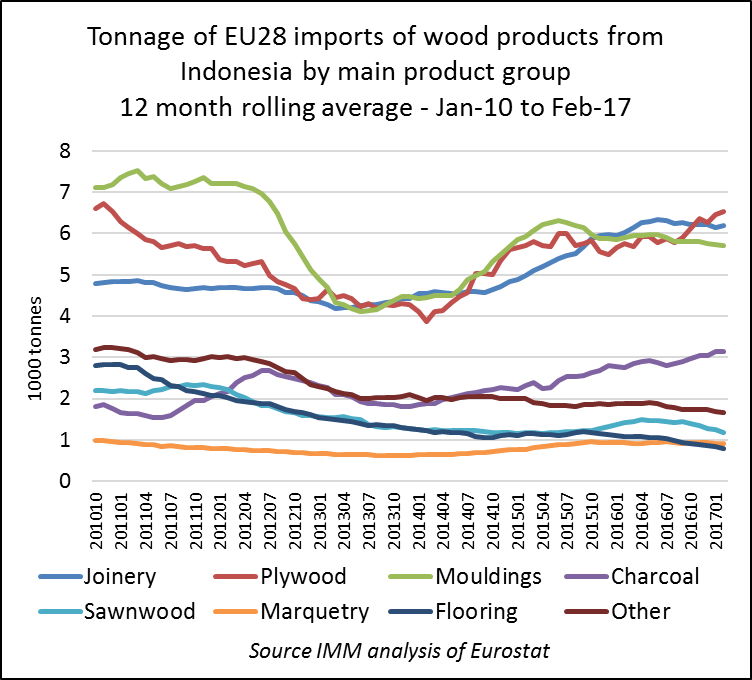

The ITTO FLEGT IMM has been gearing up to test these various assumptions, as nearly as possible on a real-time basis. To provide a taste of the kind of analysis being undertaken, the following three charts show the evolution of EU imports from Indonesia, on a monthly basis, in the 7-year period running up to, and immediately following, the issue of the first FLEGT licenses in November 2016. These charts establish the baseline against which the impact of FLEGT licensing on Indonesia’s trade with the EU trade will be assessed.

Because EU imports from Indonesia tend to be highly seasonal (furniture imports rise sharply in the run-up to Christmas and January sales, while decking importers build stock in the winter months in preparation for the spring and summer surge in demand), the charts show 12-month rolling average data to remove short-term variability and highlight long term trends.

Tonnage data is provided here rather than value data to remove variations due to very volatile exchange rates during the period – notably the 20% fall in the value of the euro (and linked currencies like the Polish zloty and Swedish krona) against the U.S. dollar between 2014 and 2015, and a 30% decline in the value of the British pound between mid-2014 and the end of 2016 (with a particularly steep plunge after the Brexit vote in May 2016).

Chart 2 shows that while pulp and paper have recently become more important in the mix of products imported into the EU from Indonesia, imports of wood products (i.e. those listed in Chapter 44 of the internationally harmonised HS system of product codes) are still the largest component.

The data shows that after a period of recovery in 2014 and 2015, EU imports of Chapter 44 wood products from Indonesia stabilised at the higher level in 2016 (averaging around 25000 tonnes per month). Still very early days, but there was no immediate discernible uptick in total EU imports of these products between December 2016 and February 2017 after the first licenses were issued.

EU imports of wood furniture from Indonesia were declining between 2010 and 2013 and then in 2014 showed slight and short-lived signs of recovery. In 2015 and 2016, the decline in imports resumed and continued through to February 2017.

Trends in pulp and paper imports from Indonesia have followed a very different path. The EU was importing small volumes of Indonesian chemical wood pulp before 2013, but these volumes fell to negligible levels in 2014 and 2015, presumably in the face of very stiff competition from Brazil. However, there were signs of a revival in EU imports of Indonesian wood pulp from the middle 2016, although the volumes involved are still very restricted.

EU paper product imports from Indonesia, while still limited, also recorded a significant uptick in 2016, averaging below 15,000 tonnes per month at the start of the year rising to over 20,000 tonnes at the end of 2016. EU paper imports from Indonesia dipped a little at the start of this year.

Chart 3 shows how EU imports of Indonesian forest products has varied in different EU member states over the last seven years. Following a surge in imports between 2014 and 2016, the UK has emerged as by far the largest single importer in the EU – which highlights the significance of imminent Brexit negotiations on the future direction of policy in relation to FLEGT licensing. The recent surge in UK imports from Indonesia has been distributed across a range of product groups including paper, plywood, and wooden doors and furniture.

Another notable trend in Chart 2 is the recent sharp rise in imports by Italy and a range of “other” EU countries not previously significant importers of Indonesian forest products. Italy has emerged as the leading destination for EU imports of Indonesian wood pulp in the last two years, and is also importing a small but rising volume of Indonesian paper products. The “other” EU countries now importing more from Indonesia are also mainly trading in Indonesian paper products and all are in South-Eastern Europe – Slovenia, Romania, Hungary, and Greece.

Chart 4 focuses in on trends in EU imports of HS Chapter 44 wood products from Indonesia. It shows that EU imports of Indonesian joinery products (mainly doors), mouldings (mainly external decking) and plywood all increased in 2014 and 2015, before stabilising and converging at around the same level of 6000 tonnes per month throughout 2016. Of these products, only plywood registered an uptick in early 2017 lending some early statistical support to anecdotal evidence of EU importers stocking up immediately following issue of the first licenses.

Notable trends in other product groups are the progressive rise in EU imports of charcoal from Indonesia – a product which incidentally is excluded from both the FLEGT licensing requirements in Indonesia and the due diligence requirements of the EUTR – and the continued slide EU imports of Indonesian wood flooring to negligible levels.

In coming months, IMM will look closely at the evolution of all these trade flows, comparing the flows with those of competing products, while also monitoring underlying economic conditions, and factors such as exchange and freight rates with an important bearing on relative competitiveness.

The statistical analysis of trade data will be supported by a network of IMM correspondents which are currently being recruited to liaise with relevant authorities and keep track of important developments on the supply side in Indonesia and other VPA Partner countries, and to undertake market assessment interviews with traders and other interests in seven EU countries which together account for over 90% of all imports of wood products from VPA partner countries into the EU (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Spain and the UK).

ETTF forecasts general stability in European tropical wood trade in 2017

The European Timber Trade Federation’s latest newsletter includes a commentary on the tropical hardwood trade in Europe by Armand Stockmans, Director of Belgium-based Somex Wood Import. Mr Stockmans suggests there will be no seismic trends this year, although there are concerns beyond trading factors, such as the extent to which FLEGT-licensed timber will impact demand for certified sustainable timber.

According to Mr Stockmans, while 2016 ended with a slowdown, and individual markets are showing a range of trends, overall indicators point to general stability. France, for instance, remains difficult. Prices and volumes are low and turnover decreasing. However, the Netherlands is picking up with timber and construction sectors ahead nearly 9.5% in the last three months. Initial 2016 growth in Belgium petered out in the second half. But currently the situation looks stable. Meanwhile, Spain is in better mood and consumption is increasing.

The supply side looks reasonably calm, says Mr Stockmans, with availability and price trending static or down for some species, but up for others. Asian demand is picking up again in Africa and some species like Tali and Azobe logs are difficult to get. However, Sipo prices are level and Iroko is rising, but slowly. FSC Ayous is scarce and demand is strong. But Padouk availability has improved, thanks to lower demand from China and India. In fact shortage turned into a surplus, although, with strong Belgian consumption and Asian buyers returning, this could evaporate.

Mr Stockmans observes that sapele prices are up again too; 5% generally, and 10% for fixed sizes. The basis of this though is the positive Dutch market, which is moving increasingly to finger-jointed product in sapele and meranti. After increases in heavier variants Nemesu and Bukit, Meranti prices have plateaued at a higher level. Suppliers of Brazilian decking also upped prices, which buyers, mainly in France, refused to pay. Once existing stock is exhausted, however, Mr Stockmans expects that these increases will feed through.

Mr Stockmans also notes demand increases for finger-jointed laminates in all European countries – presenting an opening for using lesser known species.

Mr Stockmans believes that the arrival of the first FLEGT-licensed timber from Indonesia is positive overall but also suggested that availability of FLEGT-licensed timber could lead buyers and suppliers settling for legally assured

only and not progressing to FSC or PEFC-certified material. Mr Stockmans observes that “in Africa we’re already hearing ‘Our FLEGT VPA will soon be implemented, we don’t need to do anything until then’ – to minimise these risks, while welcoming FLEGT-licensing, the trade should emphasise that our goal is legality and sustainability.”

The ETTF newsletter is available at: http://www.ettf.info/sites/ettf/files/ETTF%20Newsletter%20Winter-Spring%202017.pdf

EU Parliament proposes that EUTR be extended to other commodities

The European NGO Earthsight reports that on 4th April, the EU Parliament passed a ‘Resolution’ calling for action by the world’s largest economic bloc to urgently address tropical deforestation, including regulations to address the EU’s role in driving the destruction through its imports of agricultural commodities grown on illegally deforested land.

The EU Parliament report repeatedly cited a 2014 study for Forest Trends written by Earthsight’s Director, Sam Lawson, which showed that nearly half of all recent tropical deforestation is the result of illegal clearing for commercial agriculture and that this destruction is driven by overseas demand for agricultural commodities, including palm oil, beef, soy, and wood products. The legislators described themselves as being ‘alarmed’ by the associated findings by forests and rights NGO Fern, which estimated that a quarter of all illegal deforestation commodities were destined for the EU.

The resolution received near-unanimous support from the Parliament’s Environment Committee, which includes representatives from across the political spectrum and all EU member states. Though the Resolution was focused mainly on palm oil, it recognised the need for action by the EU in relation to other agricultural commodity imports linked to deforestation, such as soy and beef.

The Resolution calls on the European Commission to urgently develop an EU Action Plan on Deforestation which would “include concrete regulatory measures to ensure that no supply chains and financial transactions linked to the EU result in deforestation and forest degradation”.

The Parliament specifically called on the EU to enact new laws regarding forest-risk agricultural commodity imports along the lines of those already passed on timber in the EUTR.

The Resolution won’t change anything on its own – since the power to introduce new laws in the EU lies with the European Council and not Parliament – but Earthsight note that it sends a strong signal that one of the world’s largest markets for agricultural commodities will no longer tolerate its imports contributing to tropical deforestation.

PDF of this article:

Copyright ITTO 2020 – All rights reserved