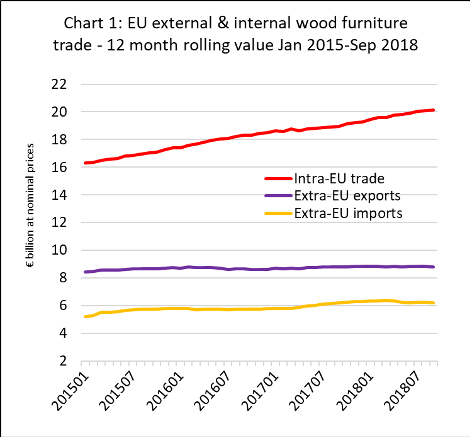

The latest Eurostat trade data for EU wood furniture trade indicates that the trends reported by ITTO MIS in September 2018 (Volume 22, Number 18) have continued; internal EU trade is rising, whereas external trade is broadly flat, both on the import and export side (Chart 1)

Internal EU trade in wood furniture, which increased 4% to €19.3 billion in 2017, increased a further 6% in the first nine months of 2018. The rise in internal EU trade is driven mainly by exports from Poland, particularly to Germany, and from the Netherlands to several neighbouring countries including Germany, France and Belgium. Wood furniture production is rising in Poland, while more imports into the EU from outside the region are now being funnelled via the Netherlands.

Meanwhile the pace of EU wood furniture exports to non-EU countries, which were flat at €8.7 billion in 2016 and 2017, continued at the same rate in the first nine months of 2018. EU exports to the USA, China and Russia have increased slightly this year but these gains have been offset by declining exports to Switzerland, Norway, Canada and UAE.

Wood furniture imports into the EU from outside the region increased 9% to €6.3 billion in 2017. Import value in the first nine months of 2018 was €4.7 billion, 1.6% less than the same period in 2017. After a strong start last year, imports slowed a little from May 2018 onwards.

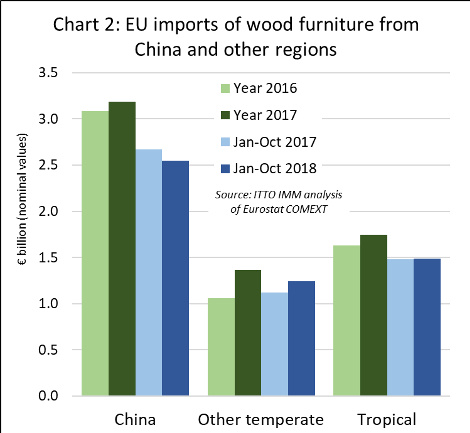

Fall in EU wood furniture imports from China and the tropics in 2018

After making gains in 2017, EU wood furniture imports from China, by far the largest external supplier, fell 5% to €2.55 billion in the first 10 months of 2018.

During the same period, EU imports of wood furniture continued to rise from other temperate countries, mainly bordering the EU. EU imports from these countries increased 11% to €1.25 billion in the first 10 months of 2018, building on a 28% gain recorded the previous year. The biggest gains in 2018 were made by Ukraine, Belarus, Russia, USA, Bosnia, and Turkey.

After a slow start to the year, EU imports of wood furniture from tropical countries picked up pace in the second half of 2018, and totalled €1.49 billion between January and October 2018, slightly exceeding the 2017 level (Chart 2).

In recent years China’s competitiveness in the EU wood furniture market has been impeded as prices have risen on the back of growing domestic demand and new laws for pollution control pollution in China. EU furniture importers also continue to question the variable quality of product imported from China and some have struggled to obtain the legality assurances required for EUTR conformance when dealing with complex wood supply chains in China.

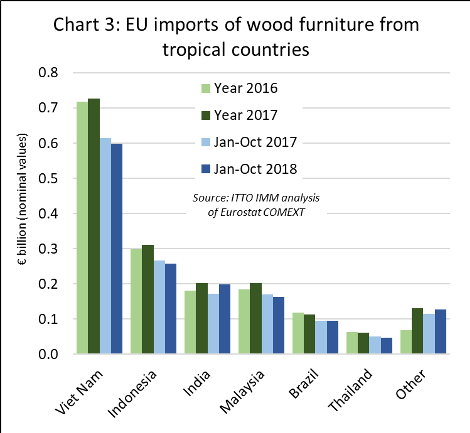

The main South East Asian supply countries have all followed a similar trajectory in the EU wood furniture market in the last two years. A rise in EU imports in 2017 was followed by a decline in 2018.

After increasing 1% to €730 million in 2017, EU imports from Viet Nam fell 3% to €599 million in the first ten months of 2018. Imports from Indonesia increased 4% to €311 million in 2017 but fell back 4% to €257 million in the first ten months of 2018. Imports from Malaysia increased 10% to €203 million in 2017 and were 4% down at €163 million in the first ten months of 2018.

In contrast, EU wood furniture imports from India have continued to rise, up 15% to €199 million in the first ten months of 2018 after a 12% increase to €202 million for the whole of 2017. Imports from Brazil were €57 million in the first ten months of 2018, matching the 2017 level (Chart 3).

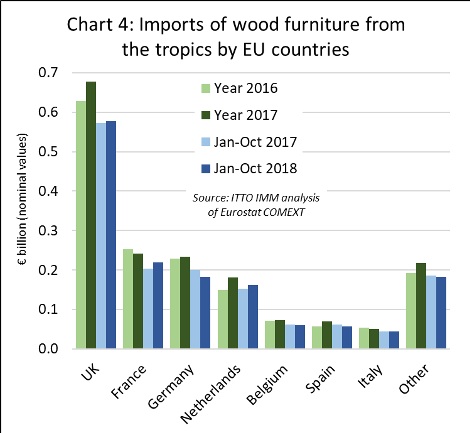

There were also shifts in the destinations for wood furniture imported into the EU from tropical countries in the first ten months of 2018. Imports in the UK, the largest market, were €577 million between January and October 2018, 1% more than the same period in 2017. There were also rising imports in France (+8% to €219 million) and Netherlands (+6% to €163 million).

However, in the first ten months of 2018 these gains were offset by falling imports of tropical wood furniture in Germany (-9% to €182 million), Belgium (-3% to €61 million), Spain (-7% to €57 million), and Italy (-2% to €44 million) (Chart 4).

IMM report examines impact of FLEGT licensing in furniture sector

With further support, development and communication of FLEGT and FLEGT licensing can play a role to underpin tropical timber product market share in the highly competitive European furniture sector. This is according to the latest survey by the Independent Market Monitor (IMM), an ITTO project funded by the EU (see www.flegtimm.eu).

The core aim of the IMM scoping study of procurement in the EU furniture industry is to gauge the sector’s perceptions of the value, impacts and process of sourcing products from supplier countries engaged in the FLEGT VPA process.

The report is based on individual country surveys undertaken by the IMM’s network of correspondents in seven lead importing countries. These were the Netherlands, UK, Germany, France, Italy, Spain and Belgium, which between them account for 83% of all furniture imported into the EU from VPA partner countries.

The key rationale of the survey is that assembled wood furniture consistently comprises 40% of the value of EU timber and wood products sourced from FLEGT VPA partner countries. So, canvassing furniture sector opinions of the VPA initiative and FLEGT licensing offers valuable lessons for the development of EU market awareness and penetration of VPA-sourced and licensed.

“[The aim is] to provide a preliminary assessment of the current and potential role of FLEGT licensing to improve market access for wood furniture from VPA countries in the EU, and to recommend a strategy to optimise the benefits of FLEGT licensing [in this respect],” states the report.

The study was also designed to provide a comprehensive baseline of perceptions and impacts of the FLEGT VPA initiative in the wood furniture sector in order to generate recommendations for IMM’s long term monitoring of the industry.

The report recognises that VPA country furniture and furniture product suppliers face in the €36 billion EU furniture arena a ‘crowded and fiercely competitive market’. The EU furniture industry comprises an estimated 130,000 companies, and 87% of wood furniture sold in the EU market is also made in Europe.

The basis of the survey comprised semi-structured interviews with 47 European companies, representing the spectrum of business type, from very large furniture retailers, to medium-sized manufacturers and distributors. Between them these imported indoor and outdoor furniture, plus wood furniture components and raw materials. They had sourced from a combined total of nine of the 15 VPA-engaged countries and altogether dealt with over 850 individual foreign suppliers.

The companies were asked about their perceptions of quality, price, lead times from order to delivery, logistics (the ease of moving products) and the range of products available from various countries and regions.

When asked to compare these variables on a country-by-country basis, it was clear that both western and eastern European EU countries were perceived as most competitive across the range of factors considered. The third-most competitive region identified was that of non-EU countries in eastern Europe. Viet Nam, Indonesia and China were perceived to be the next-most competitive.

The survey included questions on purchasing policies. Around one-quarter (11 of 47) of the companies interviewed did not have written environmental purchasing policies. For those that did have policies, the dominant feature was a requirement for “legality” or legal compliance regarding wood origin or trading (20 companies); the remainder (16 companies) were pro- certification, with a preference for the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification and/or the Forest Stewardship Council.

Products licensed under the EU FLEGT initiative were valued by 45% of those interviewed (typically those sourcing from Indonesia). An additional 19% of those interviewed stated that FLEGT licensing could play a role in their purchasing decisions if it were available in other countries.

Overall, the companies interviewed were positive towards the FLEGT process, although the lack of availability of licensed products from countries other than Indonesia was a common concern. Some respondents expressed doubt that the FLEGT process had led to on-the-ground improvements in forest governance.

The chief benefit identified for those favourably disposed towards FLEGT licensing centred on the linkage with the EU Timber Regulation and the simplified due-diligence process.

The study asked interviewees for their views on the outlook for tropical timber in the European furniture trade. Forty-three percent considered that the market for tropical wood furniture would grow or stabilize in the next decade, and 32% thought demand and volume would shrink (25% expressed no opinion).

The wide range of alternative materials and consumer and specifier attitudes towards tropical timber were seen as the main negative drivers.

Fashion largely drives the style and design of wood furniture, with end consumers destined to buy 80% of production. A complex web of interconnected drivers determines the choice of wood and accompanying colours and features. Consumers, retailers and manufacturers have a huge range of options for materials, and the choice of wood in furniture per se is no longer guaranteed.

The report concludes that ‘licensed timber alone will not reverse the trends that are [negatively] impacting on tropical wood in Europe’. However, it does have value and a role to play here, ‘as a tool to be utilised to form part of the process of building confidence in tropical timber in a wider [strategy] that might help maintain market share’.

This strategy, the report notes, would also require a wider range of players’ involvement, including ‘major retailers, trade associations, national governments, NGOs, architects, and other opinion formers’.

Wood furniture market perceptions of FLEGT licensing, the report concludes, are that it “lacks the glamour of third party SFM certification where sustainability is the main focus” which currently limits its consumer-facing role. At the same time, the report suggests FLEGT licensing can offer “assurance to business-to-business buyers operating at the base level of responsible purchasing”.

The report makes the following recommendations:

- Minimize the bureaucracy involved in the process of importing FLEGT-licensed timber to maximize the business benefits for operators.

- Encourage those companies not yet using FLEGT-licensed timber to do so.

- Demonstrate the benefits of the FLEGT-licensing scheme in Indonesia to build trust.

- Clarify within the trade the impacts and achievements of FLEGT-licensed timber and timber legality assurance schemes.

- Speed up the introduction of FLEGT-licensed timber supplies from other VPA countries

- More details, including full report download: https://www.flegtimm.eu/index.php/reports/special-studies/76-imm-eu-furniture-sector-scoping-study-flegt-can-impact-european-furniture-market-2

ETTF Secretariat shifts from Netherlands to Germany

The secretariat of the European Timber Trade Federation (ETTF) is moving from the Netherlands to Berlin. The move follows the announcement that André de Boer is stepping down as ETTF Secretary General in 2019, handing over the reins to Thomas Goebel, Chief Executive of German Timber Trade Federation GD Holz.

The first quarter of 2019 will see a transition process, with Mr Goebel officially taking on the role by April 1, combining it with his position at GD Holz.

Mr de Boer, who is a commercial lawyer by profession, is a regular ITTC delegate and member of ITTO’s Trade Advisory Group, and has often chaired the ITTO Market Discussion. He took over at the helm at the ETTF ten years ago after its formation from an amalgamation of European timber trade bodies. Prior to that he was Managing Director of the Netherlands Timber Trade Federation (VVNH) for 20 years. His time at the ETTF, he said, has been both challenging and exciting.

“The European timber importing sector in this period has had to adapt to major changes; concentration of the industry and a decline in tropical timber trade, as well as the implementation of the EU Timber Regulation,” he said. “But the trade has evolved and moved with the times, and at the same time the ETTF has gained relevance throughout the international market as advocate of a legal and sustainable, but also a commercially significant and dynamic industry.

“We are now an integral part of the conversation on climate change and the development of a low carbon bioeconomy. There’s also recognition at government level that a commercially viable forestry and timber industry is integral to maintenance of the forest resource; it’s widely accepted that it’s a case of use it or lose it.”

Mr de Boer said now was the time to hand over to a new team to take the organisation forward and exploit the opportunities to grow the European timber market.

Mr Goebel said he looked forward to his new role. “The ETTF has equipped itself well to master the challenges and realize the opportunities to come for the timber trade and is well placed to further strengthen representation of its members interests,” he said.

In another strategic move for the future of the ETTF, its annual general meeting in 2018 decided that it should join the European Confederation of Woodworking Industries, Brussels-based CEI-Bois, where a key focus will be helping develop a new timber trade segment.

“CEI Bois, with its close connection to the EU in Brussels, will further serve the interests of the trade through this separate trade pillar, in which the ETTF will play a leading role,” said Mr Goebel. “It’s decisive that we develop this facility.”

At present the ETTF has 18 member associations in 16 countries.

ISO publishes chain of custody standard for wood products

ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) has published a new, voluntary standard for chain of custody (CoC) of wood and wood-based products (together with cork and lignified materials other than wood, such as bamboo, and their products).

While the standard does not cover forest management, it can be used to transfer information about the source of the wood-based product.

According to ISO, the standard is intended to enable tracking of material from different categories of source to finished products and has several purposes. It can facilitate business-to-business communications by providing a common framework that allows businesses to “speak the same language” when describing their chain of custody system.

Purchasers can use the standard document to evaluate the information they receive from suppliers to help identify suitable input material. This information can then be used together with a set of specified criteria to determine whether a product/input material fulfils the conditions for the intended use. Other standards and certification schemes can use the standard as a reference regarding chain of custody systems.

More details: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:38200:ed-1:v1:en

PDF of this article:

Copyright ITTO 2020 – All rights reserved